The Earliest History of the Evolution of Social States in the Nineteenth Century Europe

Journal: Social Evolution & History. Volume 19, Number 1 / March 2020

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/seh/2020.01.07

Until the second half (or even the last few decades) of the nineteenth century states tended to play only a minimal role in social security. By the mid-nineteenth century, some Western European countries developed the first prototypes of the modern pension system. The real history of modern social security dates back to the laws adopted in Germany in the 1880s. In this paper we consider in more detail the examples of the early development of social legislation in the two pioneer countries, Germany and the UK.

Julia Zinkina, Senior Research Fellow, International Laboratory for Demography and Human Capital, RANEPA more

Alexey Andreev, Associate Professor, Faculty of Global Studies more

The late nineteenth – early twentieth centuries witnessed the birth of the modern social state, as the states started creating social security systems for their populations. Currently Article 22 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states the following:

Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security and is entitled to realization, through national effort and international co-operation and in accordance with the organization and resources of each State, of the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and the free development of his personality.

Pension systems are now available in approximately 170 countries, compensation schemes for occupational injuries are in force in about 160 countries, benefits in case of illness can be found in 130 countries, and unemployment benefits have been introduced in about 60 countries (Schmitt et al. 2014). However, the path to this state of affairs was quite long and took more than a century.

Until the second half (or even the last few decades) of the nineteenth century states tended to play only a minimal role in social security. Thus, in Western European countries in the early nineteenth century this role was limited to providing state pensions to the injured veterans of military campaigns1 and high-level government officials; in some cases, similar privileges were conferred upon the workers of state enterprises and mines. One can also mention the English Poor Law, under which a system of help to extremely poor people developed (Tomka 2013: 155; Hannah 1986: 9). Apart from families, the main source of social support were various funds and mutual societies which provided support for their members in difficult life situations out of the means received as membership fees (a particularly long history of such organizations could be found in the mining business, which bears high risk for life and health). However, membership in such organizations was voluntary. They consisted mainly of people who could afford to pay membership fees; and social support provided by them was very far from universal (e.g., they rarely paid old-age pensions) (Hannah 1986: 6).

By the mid-nineteenth century some Western European countries developed the first prototypes of the modern pension system. Thus, the United Kingdom introduced a pension scheme for civil servants in 1859, which was funded entirely by the state (and did not require contributions from the civil servants themselves). According to this scheme a retired official received for each year of service a 1/60 of his income in the last year of service (but not more than 2/3 = 40/60 of his income in the last year of service) (Hannah 1986: 9). The largest private businesses of the United Kingdom – the railway companies – had rather well-developed pension schemes for their management personnel and clerks (but not for the workers) by the 1880s. In a typical scheme (the membership in which was compulsory) the employee transfered 2.5 per cent of his salary to the fund, and the same amount was transferred to the fund by the employer. The size of a pension was determined by average earnings and the number of years in service. For example, pension equaled 25 per cent of average earnings after ten years of service and 67 per cent after 45 years of service (Hannah 1986: 9–10).

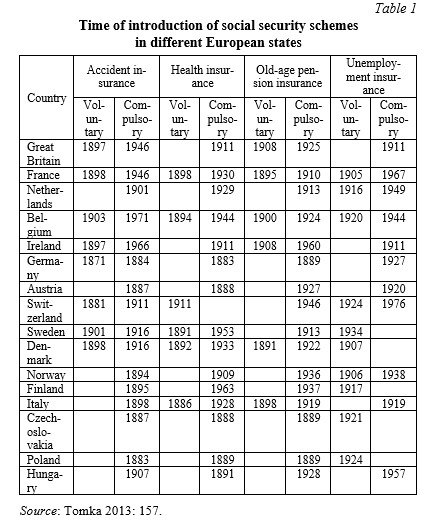

The history of modern social security dates back to the laws adopted in Germany in the 1880s. The first state program of compulsory health insurance for industrial workers was introduced by the ‘Iron Chancellor’ Otto von Bismarck in 1883. It was followed by the insurance program against accidents (1884), and insurance for old age pensions (1889). The spread of social security systems throughout Europe was extremely quick. Borrowing the elements of German system and complementing them with their own experience, all Western European and several Eastern European countries had at least one active program of state health insurance, or accident insurance, or old-age pensions by 1901. At the time of the First World War all three types of programs were functioning in most Western European countries (Tomka 2013: 156).

Below we will look in more detail at the examples of the early development of social legislation in the two pioneer countries, Germany and the UK.

THE EXPERIENCE OF GERMANY

To understand the reasons behind the emergence of national social legislation in Germany in the 1880s one has to think of the socio-political and socio-economic context in which it occurred. Many scientists suggest that the initiatives designed by the Iron Chancellor made use of the advanced German neo-absolutist bureaucracy (which inherited the Prussian traditions) in order to mitigate the liberal and, in particular, the socialist calls made by the labor movements. The program sought to meet the reasonable socialist demands that could be implemented within the established social and political order (Hicks, Misra, and Ng 1995: 330; see also Zollner 1982).

The German social legislation of the 1880s included three main laws. The first law, issued in 1883, concerned the mandatory (for workers in certain industries) health insurance. Two-thirds of the medical system underlying health insurance were funded by workers, and one-third was financed by employers. National regulation in this field was absent. Each worker was a member of a health insurance fund of his own company, or a local insurance company, a guild fund, or a private foundation. All the employees of certain industries with an income of less than 2,000 marks per year were subject to insurance. During the period of disability, the employee received 50 per cent of his salary, free medical treatment and essential drugs. The related costs were assumed by the insurance company which made contracts with private physicians practicing in the relevant area (Gibbon 1912: 2–7; Frerich and Frey 1993: 97–99; Zollner 1982: 35–37).

Thus, the usual bilateral relations between the doctor and the patient changed to a tripartite relationship between the insurance company, the doctor, and the patient. It was the principal innovation of this law. Getting free medical care was also a significant step forward compared with the reimbursement of medical expenses practiced previously. The number of the insured in 1885 doubled in comparison with the period before the introduction of the law (4.3 million people compared to about 2 million). By 1900 this number grew to 9.5 million, and by 1914 it increased up to 15.6 million, encompassing approximately a quarter of the total population. The increase was largely due to the growing number of employees in the sectors covered by the insurance schemes, but also due to the inclusion of many new areas into this scheme (especially workers employed in agriculture). In 1910 there existed 23,000 health insurance schemes (Tampke 1981: 76–77; Zollner 1982: 35–37).

The second law, passed in 1884, was related to insurance against accidents. Employers were ordered to organize ‘professional associations’ in various industries that were to be controlled by the newly established governmental insurance service. Funding for payments in case of an insured event was entirely on the employer. Upon becoming disabled the employee received a lifetime pension (the minimum size was set by the state, a possible increase depended on the previous earnings and years of service) (Frerich, Frey 1993: 95–97; Tampke 1981: 76–77; Zollner 1982: 27–29).

The first version of the law on compulsory accident insurance covered the workers of mines, shipyards and factories, as well as roofers and masons. Amendments to this law extended it also to workers in transport (including railways, canals, and river transport), employees of postal and telegraph systems, soldiers and officers of the army and navy, as well as to people engaged in agriculture, construction, long-distance trade, fishing, etc. The updated National Insurance Act of 1911 covered almost all professions. Technical officers and clerks were to be insured if their income did not exceed 5,000 marks (equivalent to 250 British pounds); workers were to be insured regardless of income (Dawson 1913: 102; Rubinow 1916a: 30–31). By 1914 the number of the accident-insured reached 28 million people (Tampke 1981: 76).

Finally, the third law, passed in 1889, obliged the workers and employers to make contributions (in equal parts) to the scheme of old-age pension insurance. Subject to this type of insurance were all workers with an income of less than 2,000 marks per year. Pensions were received by persons older than 70 years (later this threshold was lowered to 65 years of age) who had worked for at least 5 years. In 1913, 1.2 million people were receiving old-age pensions in Germany (Zollner 1982: 28–31).

THE EXPERIENCE OF GREAT BRITAIN

In the UK, the emergence of modern social legislation took place in a very different social and political context than in Germany. The reform was initiated by a coalition of Liberals and Laborites (Hicks, Misra, and Ng 1995: 330). A package of initiatives in the social sphere was associated with a liberal UK government that came to power in 1906. By the end of 1908 the Government carried out at least six legislative initiatives marking a significant social reform: Workmen's Compensation Act of 1906 and five laws of 1908, including Children Act, Incest Act, Probation of Offenders Act, Labor Exchanges Act, and the Old Age Pensions Act (Jones 1994: 81). The year 1908 is considered to be a watershed:

The year's symbolic power is significant: it marks the transition from a Britain skeptical of state involvement in public affairs to one willing to accept its offers of help; it coincides with the institutional death of the self-help movement that defined Victorian Britain; and, in some ways, it foreshadows the relocation of British working-class policymaking from the industrial North to the chambers of Parliament in London (Broten 2010: 2).

The Workmen's Compensation Act of 1906 introduced compensation for occupational injuries to be received by representatives of dangerous professions. Employers were obliged to insure their employees. This law was the first step of the formation of national accident insurance scheme.

The Children Act was a consolidating law that brought together the measures previously ‘scattered’ in 39 different legislative acts aimed at protecting the lives of young children and preventing their ill-treatment. Among many other measures, it was declared a crime to allow children to smoke or to beg. For the first time the Children Act introduced the concept of juvenile delinquent behavior, set up special courts to hear cases in which the accused were minors, as well as a system designed to replace imprisonment by other forms of correctional facilities. In contrast to the Victorian policy, the law stated a set of rights and obligations of minors as full members of society (Bruce 1968: 189–194).

The Probation of Offenders Act laid foundation for the development of alternatives to prisons in the penitentiary system, leaving some convicts an opportunity to live in the community under the supervision of a special probation officer, whose duty was to advise such prisoners and assist them to embark on the path of correction (Jones 1994: 81).

Under the Labor Exchanges Act a network of labor exchanges was established across the country, where the unemployed could get information about available vacancies. By 1913, there were 430 major labor exchanges and more than 1,000 small offices in rural areas (Jones 1994: 81).

Of special note is the story of pension legislation development in the United Kingdom. The first pension administration proposals were based on the insurance system – for example, the suggestion of the British philanthropist Blackley of 1878, according to which the government was supposed to create a fund to which every working citizen would have to make a certain contribution so that these means would be used to finance sick pay at the rate of 8 shillings per week, and old-age pension at the rate of 4 shillings per week (Gilbert 1965: 558; Collins 1965: 252–253). The House of Lords rejected Blackley's proposal. However, the heated debate on the necessity of old-age pensions continued; one of the strong arguments in their favor was that they could provide more adequate and effective means of helping the poor than the practices accepted under the clearly obsolete Poor Law (see, e.g., Sires 1954: 248–253). Finally, in 1908 the Liberal government of Great Britain announced introduction of a state selective distributive scheme for old-age pensions. The payments amounted 5 shillings a week for persons older than 70 years with low income (less than 20 pounds a year); those with incomes above £20 but less than 31 pounds 10 shillings a year were to receive a shilling per week; elderly people with higher incomes did not receive pension at all (Hannah 1986: 15; Collins 1965: 258). The total cost of the system amounted to about £6 million per year, funded from general taxation (Sires 1954: 248–249; Bruce 1968: 153). By 1912, 60 per cent of population aged more than 70 received pensions under this scheme.

The distribution of the new pensions through post offices and their clear separation from the poor law authorities made them a highly acceptable substitute for poor relief. Thus began that process (still incomplete) of removing the stigma of welfare provision from the minds of needy beneficiaries. The new pensions were extremely popular (Hannah 1986: 16).

Finally, in 1911 the Law on National Insurance was adopted, covering areas such as health insurance and unemployment insurance (Gibbon 1912: 40–43). Health insurance covered all workers aged 16–70 years earning less than £250 per year, as well as workers not engaged in manual labor and earning less than £160 a year. The scheme was financed by the employee, the employer and the state. The employee could receive sickness benefit (10 shillings a week), disability allowance (5 shillings a week), as well as a lump-sum payment on the birth of a child (30 shillings, or twice as much if both mother and father of the child were insured). The insured worker could also choose a doctor from a list compiled by the insurer, if necessary (Jones 1994: 85–86; Bruce 1968: 183–189).

All these laws laid the foundations for the development of social policy in Great Britain, as well as in many of its colonies and protectorates, for many decades to come (Rubinow 1916b: 26).

THE EMERGENCE OF SOCIAL SECURITY IN THE GLOBAL HISTORY

In the early twentieth century a researcher of the history of social security Isaac Max Rubinow pointed out:

There is no doubt that the modern conception of social insurance – as a system carrying with it compulsion, state subsidies, and strict state supervision and control – has reached its highest development in modern Germany, so that any system embodying, to any large degree, all these three elements, may be described as the German system. But even preceding the German bills of 1881 and acts of 1883 and 1884, numerous acts were passed by many German, as well as many other European states, which embodied some or all of the three leading principles of this German system. … It may be admitted that it was Bismarck who contributed to the history of Social Insurance the first application of State Compulsion on a large national scale. But he did not ‘invent’ the principle of workmen's insurance, nor that of state insurance, nor that of compulsion. In the decade prior to the introduction of the compulsory insurance system, there existed in Germany a multitude of organizations, part of them very old and part new, some compulsory, some voluntary, some local, some national, some mutual and based on other plans; some of them were connected with especial establishments, such as special mines, railways, etc., some were connected with trade unions; many of them were connected with guilds. In other words, there were already existing all the elements out of which, with the unifying power of a large state, the system of national compulsory insurance could easily be built (Rubinow 1916b: 13–14).

Indeed, the legislation introduced in Germany in the 1880s can be considered a logical continuation of the Prussian legislative tradition in social sphere. This tradition was especially strong in labor regulation in the mining industry, where as early as in 1776 the work of miners was legally restricted to an eight-hour working day and six-day working week, and children's and women's work at mines was banned. In the early nineteenth century there was a very well-developed for its time insurance system under which miners were given free treatment in case of illness or accident, the payment for the entire time spent at the hospital, as well as regular payments in case of disability (Tampke 1981: 72–73; Frerich, Frey 1993: 62–66). In the 1840s, the government changed the law on guilds. New forms of guilds of craftsmen and factory workers were controlled by the state and administered the funds of payments to illness, disability and old-age pensions for their members. In urban and rural areas there were numerous health insurance funds for those who did not belong to any guild (Tampke 1981: 72–73; Frerich, Frey 1993: 56–58). All these factors make some researchers conclude that

…the social welfare tradition existed long before the 1880s. Admittedly these laws covered predominantly the handicrafts system, but until the middle of the century artisans and craftsmen did provide the bulk of the urban work force. This changed when rapidly increasing industrialization, which had set in by the second half of the nineteenth century, spelt doom for the handicraft system and when a growing number of workers found themselves employed in industries which were not covered by legislation. … So in the 1880s it was not a new leaf that was turned in the history of social welfare in Germany but a return to the old principle of state interference applied to a new economic background (Tampke 1981: 73).

However, one can hardly wholeheartedly agree with this conclusion in the context of the history of globalization. Of course, the principles introduced in the 1880s were far from unprecedented. However, the combination of these principles was truly unprecedented in the scale and global effects. Indeed, the introduction of compulsory accident insurance, compulsory (at first for certain spheres of activity) health insurance, and the system of old-age pension insurance actually gave impetus to the development of three fundamental trends of social security. German experience was borrowed by many European countries, if not in terms of specific practical details (which were commonly borrowed as well), then in terms of the idea of organizing national social systems in these areas. From Europe these ideas spread worldwide.

The German example of a statewide, universal, and compulsory system of sickness insurance was first followed by Austria (1888) and Hungary (1891) (Rubinow 1916b: 20). After about twenty years they were followed by many other countries which previously had voluntary sickness insurance. Say, in 1909–1913 the compulsory systems of sickness insurance were introduced in Norway, Serbia, Great Britain, Italy, Romania, and Russia. More and more countries understood that they had failed to involve the neediest groups within the working class into the sickness insurance system by any measures except for introduction of a system of compulsory sickness insurance (Rubinow 1916а: 21).

Thus, the the late nineteenth – early twentieth century was the time marked by a radical transition to a new type of state – the state providing a national-level social support not only to particular individuals in need, but to whole social groups and categories. This is the time when a new type of state – the welfare state – was born.

NOTES

* This research has been supported by Russian Science Foundation project No 15-18-30063.

1 For example, the USA provided pensions to the veterans of the Civil war, even though other significant directions of social security developed here much later than in Western Europe (see, e.g., Skocpol 1993).

REFERENCES

Broten, N. 2010. From Sickness to Death: The Financial Viability of the English Friendly Societies and Coming of the Old Age Pensions Act, 1875–1908. Economic History Working Papers (135/10). Department of Economic History, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK.

Bruce, M. 1968. The Coming of the Welfare State. New York: Schocken Books.

Collins, D. 1965. The Introduction of Old Age Pensions in Great Britain. The Historical Journal 8 (2): 246–259.

Dawson, W. H. 1913. Social Insurance in Germany 1883–1911. London: Scribner.

Frerich, J., and Frey, M. 1993. Handbuch der Geschichte der Sozialpolitik in Deutschland. Band 1: Von der vorindustriellen Zeit bis zum Ende des Dritten Reichs. Munchen, Wien: R. Oldenburg Verlag.

Gibbon, I. G. 1912. Medical Benefit. A Study of the Experience of Germany and Denmark. London: P. S. King & Son, Orchard House, Westminster.

Gilbert, B. B. 1965. The Decay of Nineteenth-Century Provident Institutions and the Coming of Old Age Pensions in Great Britain. The Economic History Review, New Series 17 (3): 551–563.

Hannah, L. 1986. Inventing Retirement: The Development of Occupational Pensions in Britain. Cambridge University Press.

Hicks, A., Misra, J., and Ng, T. N. 1995. The Programmatic Emergence of the Social Security State. American Sociological Review 60 (3): 329–349.

Jones, K. 1994. The Making of Social Policy in Britain, 1830–1990. London and New Brunswick, NJ: Athlone Pr.

Rubinow, I. M. 1916а. Standards of Health Insurance. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Rubinow, I. M. 1916b. Social Insurance with Special Reference to American Conditions. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Schmitt, C., Lierse, H., Obinger, H., and Seelkopf, L. 2014. The Global Emergence of the Welfare State: Explaining Social Policy Legislation 1820–2013. Bremen.

Sires, R. V. 1954. The Beginnings of British Legislation for Old-Age Pensions. The Journal of Economic History 14 (3): 229–253.

Skocpol, T. 1993. America's First Social Security System: The Expansion of Benefits for Civil War Veterans. Political Science Quarterly 108 (1): 85–116.

Tampke, J. 1981. Bismarck's Social Legislation: A Genuine Breakthrough? In Mommsen, W. J., and Mock, W. (eds.), The Emergence of the Welfare State in Britain and Germany, 1850–1950 (pp. 71–83). London: Croom Helm.

Tomka, B. 2013. A Social History of Twentieth-Century Europe. London and New York: Routledge.

Zollner, D. 1982. Germany. In Koehler, P. A., Zacher, H. F., and Partington, M. (eds.), The Evolution of Social Insurance, 1881–1981. Studies of Germany, France, Great Britain, Austria, and Switzerland (pp. 1–92). London: Frances Pinter (Publishers), New York: St. Martin's Press.