Perceived Impact of Globalization and Global Citizenship Identification

Journal: Journal of Globalization Studies. Volume 11, Number 1 / May 2020

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/jogs/2020.01.02

In the present research, we examined associations between perceived impact of globalization and global citizenship identification. We constructed a single-item measure of perceived impact of globalization (SIPIG) and tested its convergent and divergent validity (Study 1). The SIPIG showed adequate test-retest reliability in a sample of students (Study 2) and positively correlated with global citizenship identification in samples recruited both from within the U.S. (Studies 1, 3, 4) and outside the U.S. (Canada, Brazil, Vietnam, and India; Study 3). Lastly, SIPIG predicted antecedents of global citizenship identification in a broader model of global citizenship identification and its outcomes (Study 4). Together, the results suggest a positive association between perceived impact of globalization on the self and identifying with global citizens.

Keywords: globalization, global citizenship, identification, global awareness.

Stephen Reysen, Texas A&M University-Commerce more

Iva Katzarska-Miller,Transylvania University, Lexington more

Courtney N. Plante, Bishop's University more

Truong Quang Lam, Vietnam National University, Hanoi more

Shanmukh V. Kamble, Karnatak University Dharwad more

Natalia Assis,Texas A&M University-Commerce more

Eduardo Gregolin Moretti, Psychology and Stress Management Institute, Campinas more

Introduction

Globalization has been extensively discussed and researched in academic fields including economics, business, sociology, anthropology, and political science (Pieterse 2009). Psychologists, however, have been slow to assess the impact of globalization on individuals (Arnett 2002; Gelfand, Lyons and Lun 2011; Kapoor and Tomar 2017). Arguably, the most important contribution a psychological perspective can offer to the conversation is consideration of the impact of the world's increasing interconnectedness on identity, as globalization affords the opportunity to adopt a global identity (Hannerz 1992; Pieterse 2009). For example, by consuming media and engaging with others around the world through technology, people may feel a sense of belongingness with a global culture (Arnett 2002). Such a global identity may, in turn, be related to greater openness to diverse others and experiences (Kapoor and Tomar 2017) and shift our perspective on global problems (Melluish 2014). In the present paper we review past research showing a connection between globalization and global identity, and examine the connection between individuals' perception of the impact of globalization on the self and global citizenship identification.

Perceived Impact of Globalization

Much of the social research on globalization has focused on individuals' view of globalization as positive or negative (e.g., Das, Hui and Das 2013; Lee, He, Lee, Lin and Yao 2012) or on peoples' openness or rejection in response to globalization (e.g., Chen et al. 2016; Gelfand et al. 2011). Fewer studies have examined how globalization influences important psychological variables, such as one's sense of self. Across these studies, assessment of globalization has primarily been operationalized in two ways: measuring degree of globalization at a country level (e.g., trade flow, capital flow, international tourism, international voice traffic, number of foreign companies operating in the country) or assessing individuals' perceptions of globalization (e.g., perceived negative impact of globalization on self). For example, lower perceived negative impact of globalization was related to greater consumption of foreign media in Chinese participants (Lee, He, et al. 2009). In a similar vein, the residents of Hong Kong and Taipei (both Chinese-speaking) had more friends in other countries, were more willing to move abroad, were more fluent in other languages, and showed greater interest in foreign affairs when they held a positive perceived impact of globalization (Lee et al. 2012).

Researchers have examined the association between globalization and global identity at the level of both individuals and countries. Buchan and colleagues (2009), for example, asked participants in six countries to complete measures of participation in global relations (economic, social, and cultural) and a token assignment task reflecting contributing to the global or local community. Greater participation in global relations (i.e., globalization) was associated with greater giving to the global community. In other words, globalization was related to cooperation with distant others and, indeed, giving to the world was associated, in turn, with identifying with the world as a whole (Buchan et al. 2011). Global identity has also been found to mediate the relationship between involvement in globalization and cooperation with global others (Grimalda, Buchan and Brewer 2015). In another study, Der-Karabetian, Cao, and Alfaro (2014) sampled college students in the U.S., China, and Taiwan regarding perceived impact of globalization and global-human belonging (e.g., ‘I think of myself as a citizen of the world’). Across all three samples, participants' perceived impact of globalization was positively associated with a sense of global belonging, a finding similar to results obtained in samples of college students in the U.S., Netherlands, and Brazil (Der-Karabetian and Alfaro 2015).

Although the above results consistently find that globalization is associated with individuals' global identification, the results are far more mixed when globalization is measured at the country level. Ariely (2018) notes that the association between globalization and identification with the world is mixed. He observed a non-significant association between a country-level indicator of globalization and individuals' ratings of global identity in the World Values Survey Data. In another set of studies, Ariely (2017) observed that global identification is negatively related to xenophobic values, especially in more globalized countries. Taken together, past research has shown that when perceptions of globalization are assessed at an individual level, greater engagement with globalization (e.g., consumption of foreign media) is associated with prosocial values (e.g., less xenophobia, cooperation), global identity, and engagement with diverse others.

Global Citizenship Identification

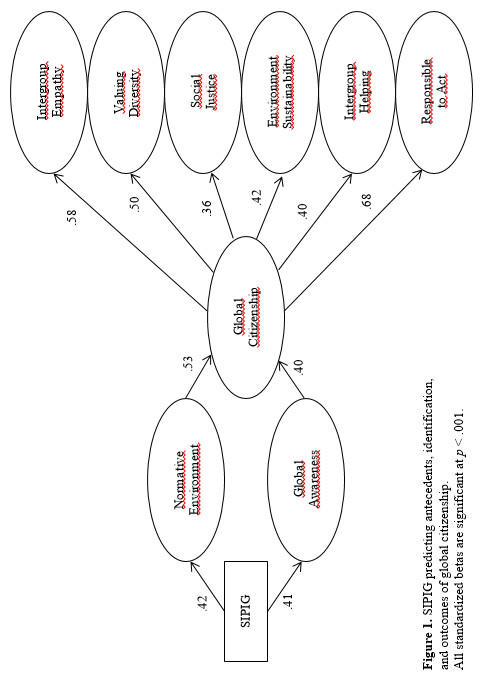

Global citizenship is defined as awareness of the world, caring about others, embracing cultural diversity, promoting social justice and sustainability, and a sense of responsibility to act (Reysen, Larey, and Katzarska-Miller 2012). Reysen and Katzarska-Miller (2013) modeled the antecedents and outcomes of global citizenship identification and found that individuals' normative environment (perception that valued others prescribe a global citizen identity) and global awareness (perceived knowledge of the world and interconnectedness with others) predict global citizenship identification (degree of psychological connection with the category label global citizen). In line with a social identity perspective (Tajfel and Turner 1979; Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell 1987), greater identification with global citizens subsequently predicts greater adherence to the group content (e.g., norms, values, beliefs, behaviors). Based on prior theorizing and lay perceptions of global citizenship (Reysen and Katzarska-Miller 2018), group norms revolve around six clusters of prosocial values: intergroup empathy (concern for others outside one's ingroup), valuing diversity (appreciation and interest in diverse cultures), social justice (attitudes related to human rights and equitable treatment), environmental sustainability (concern and action for the natural environment), intergroup helping (desire to help others outside one's ingroup), and felt responsibility to act (duty or obligation to act for the betterment of the world). This model has since been replicated numerous times (see Reysen and Katzarska-Miller 2018).

Global citizenship is conceptually related to globalization. In an effort to construct a dictionary of words related to global citizenship, Reysen et al. (2014) asked students to provide a definition of the term. The most frequently used words were categorized into ‘global citizen’ or ‘other’ in a timed task. Globalization was frequently, and quickly, categorized as relating to global citizen. These findings suggest an implicit association between the concepts of global citizenship and globalization in individuals' schemas. This result, coupled with the reviewed research on globalization across cultural contexts (e.g., Der-Karabetian and Alfaro 2015), leads us to hypothesize that people who perceive globalization as affecting them personally should report greater identification with the term ‘global citizen’, regardless of where they are from.

Overview of Present Research

The purpose of the present research is two-fold: To examine the initial validity and reliability of a single-item measure of perceived impact of globalization (SIPIG) and to test its association with global citizenship identification across cultures. Convergent validity can be tested by looking for positive correlations between the SIPIG and globalization-related measures, while divergent validity can be tested by looking for a non-significant association between the SIPIG and social desirability. Based on prior research (Der-Karabetian and Alfaro 2015; Der-Karabetian et al. 2014; Grimalda et al. 2015), we hypothesized that perceived impact of globalization on the self will be positively related to global citizenship identification across cultures.

In Study 1, the participants completed the SIPIG and measures related to globalization, global citizenship identification, and social desirability, which allowed a test of both convergent and divergent validity of the SIPIG as well as a test of the association between the SIPIG and global citizenship identification in a U.S. sample. In Study 2, the participants completed the SIPIG at two time points to assess the test-retest reliability of the measure. In Study 3, we conducted a cross-national study (U.S., Canada, Brazil, Vietnam, and India) to examine whether the association between the SIPIG and global citizenship identification exists in non-U.S. contexts. Based on prior research (Der-Karabetian and Alfaro 2015; Der-Karabetian et al. 2014) we hypothesized a positive association regardless of sampled country. Lastly, in Study 4, participants completed the SIPIG and measures of the antecedents and outcomes of global citizenship identification. We predicted that individuals who perceived themselves as more impacted by globalization would report greater normative environment, global awareness, and global citizenship identification.

Study 1

The purpose of Study 1 was to examine the validity of a single-item measure of perceived impact of globalization and its association with global citizenship identification.

One's perceived impact of globalization is expected to be associated with globalization-related concepts such as knowledge of the world and global institutions (e.g. United Nations), engagement with others around the world, and consumption of international news. Positive associations with these items constitute a test of the SIPIG's convergent validity, while a non-significant association with social desirability is a test of the SIPIG's divergent validity. We also included measures of one's openness to globalization, positive attitude toward globalization, and orientation toward globalization (inclusive vs. restrictive). We did not make a priori predictions for these measures.

The SIPIG was designed to be face valid with respect to perceived impact while not imposing a value judgment on the impact of globalization as positive or negative. As such, we are unsure whether this measure of impact will be associated with viewing globalization favorably.

Finally, we predicted that perceived impact of globalization would be positively related to global citizenship identification, based on analogous research on global identity.

Method. Participants and Procedure

Participants (N = 275, 50.9 per cent female, 0.7 per cent other; Mage = 40.51, SD = 14.63) included Americans recruited from Amazon's Mechanical Turk ($ 0.50 compensation). Participants completed the SIPIG along with measures related to globalization, global citizenship identification, and social desirability. The globalization related measures were presented in random order. Unless noted otherwise all measures used a 7-point Likert-type response scale, from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree.

Measures

Single-item perceived impact of globalization (SIPIG). We constructed a single item (‘Globalization has a significant impact on my life’) measure of participants' perception that globalization impacts their life.

Social globalization. We adapted 15 items (e.g., ‘I use the internet to talk to people outside the U.S.’) from a prior measure (Ashiabi and Hasanen 2012) to assess the extent to which participants engage with others and media from outside the U.S. (see Table 1 for alpha).

Globalization attitude. We adopted a three-item (e.g., ‘The word globalization has a positive meaning’) measure of attitude toward globalization from prior research (Suh and Smith 2008) to assess participantsˈ degree of viewing globalization positively.

Globalization knowledge. We adapted 12 items (e.g., ‘I am knowledgeable about the United Nations,’ “I am knowledgeable about global warming’) from prior research (Buchan, Fatas and Grimalda 2012) to assess participantsˈ perceived knowledge about global issues and institutions.

Global orientations. We included a 25-item measure of global orientations from prior research (Chen et al. 2016). The measure contains two subscales including multicultural acquisition (13 items; e.g., ‘I learn and speak languages other than my mother tongue’) and ethnic protection (12 items; e.g., ‘I find living in a multicultural environment very stressful’).

Global openness. We adopted four items (e.g., ‘I have real interest in other cultures or nations’) from Suh and Kwon (2002) to measure participants' degree of openness to other cultures.

Awareness of globalization. We adapted three items (e.g., ‘I see a lot of evidence of cultural globalization around me’) from prior research (Das et al. 2013) to assess the degree of awareness of globalization.

Perceived impact of globalization. We adapted three items (e.g., ‘Political globalization affects me greatly’) from Das and colleagues (2013) to measure the perception of impact of globalization.

Global citizenship identification. We adopted five items (e.g., ‘I strongly identify with global citizens’) from prior research (Reysen and Katzarska-Miller 2017) to assess participants' degree of identification with the category term ‘global citizen’.

Social desirability. We adopted a 10-item (e.g., ‘I like to gossip at times’) measure of social desirability from prior research (Strahan and Gerbasi 1972).

Results and Discussion

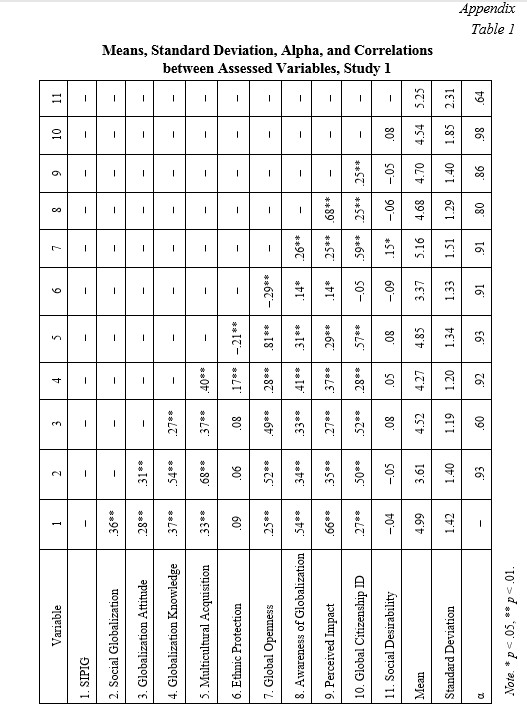

To examine convergent and divergent validity of the SIPIG we conducted correlations between the assessed variables. As shown in Table 1, the SIPIG was positively related to social globalization (engaging with international news and individuals outside one's country), having a positive attitude toward globalization, perceived knowledge of global issues and institutions, multicultural acquisition, openness toward globalization, awareness of globalization, perceived impact of globalization on the self, and global citizenship identification. The SIPIG was non-significantly related to ethnic protection and social desirability.

The results provide initial evidence of convergent (e.g., positive associations with measures related to globalization) and divergent (non-significant association with social desirability) validity for the SIPIG. In line with past research regarding global identity (e.g., Der-Karabetian and Alfaro 2015; Der-Karabetian et al. 2014; Grimalda et al. 2015), the SIPIG was also positively correlated with viewing the self as a global citizen. Although we did not predict that the SIPIG would be associated with viewing globalization favorably, significant positive correlations were observed between the SIPIG and variables reflecting openness to globalization and other cultures (e.g., global openness, multicultural acquisition). Additionally, the SIPIG was not significantly associated with ethnic protection, a scale reflecting a rejection of globalization and diverse individuals. In short, the results suggest that individuals who perceive greater impact have a positive attitude toward globalization.

Having shown initial validity for the SIPIG, we constructed a second study to examine test-retest reliability.

Study 2

The purpose of Study 2 was to examine the test-retest reliability of the SIPIG. A positive and significant correlation between assessments will show reliability compared to another single-item measure.

Method. Participants and Procedure

Participants (N = 245, 77.6 per cent female, 1.3 per cent other; Mage = 21.62, SD = 6.02) included undergraduate students at Texas A&M University-Commerce participating for extra credit or course credit toward a psychology class. Participants completed the SIPIG at the beginning of the fall semester and again at the beginning of the spring semester (about four months apart).

Materials

The SIPIG was identical to Study 1. Students completed the item at the beginning of fall (M = 4.08, SD = 1.40) and spring (M = 4.54, SD = 1.39) semesters.

Results and Discussion

To examine test-retest reliability we conducted a correlation between the two time points. The association was significant, r = .48, p < .001. As a comparison, Postmes, Haslam, and Jans (2013) found that the correlation between time points five weeks apart of a single-item measure of ingroup identification was .42. As such, the present findings are taken as evidence for the SIPIG's test-retest reliability.

We next examined whether the perceived impact of globalization is related to global citizenship in both U.S. and non-U.S. samples.

Study 3

The purpose of Study 3 was to examine the association between the SIPIG and global citizenship identification across cultures. Similar to past research showing an association between globalization and global identity (Der-Karabetian and Alfaro 2015; Der-Karabetian et al. 2014; Grimalda et al. 2015) in U.S. and non-U.S. samples, we expect to find a positive correlation between the SIPIG and global citizenship identification across samples.

Method. Participants and Procedure

Participants included undergraduate students at Texas A&M University-Commerce in the US (N = 202, 80.2 per cent female, 1.0 per cent other; Mage = 21.77, SD = 6.52), undergraduate students at MacEwan University in Canada (N = 149, 73.8 per cent female, 5.4 per cent other; Mage = 21.17, SD = 4.45), individuals solicited through friendship networks in Brazil (N = 119, 61.3 per cent female, 0.8 per cent other; Mage = 30.87, SD = 9.12), undergraduate students at Vietnam National University in Vietnam (N = 147, 70.1 female, 0.7 per cent other; Mage = 18.54, SD = 0.98), and graduate students at Karnatak University in India (N = 192, 76.6 per cent female; Mage = 21.59, SD = 1.60). The surveys in the US, Canada, and India were administered in English. The survey in Brazil was administered in Portuguese and Vietnamese for participants in Vietnam (both were back translated). As part of a survey regarding a variety of topics (e.g., fandom, dating behavior), participants completed the SIPIG and a measure of global citizenship identification. All measures used a 7-point Likert-type scale, from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree.

Measures

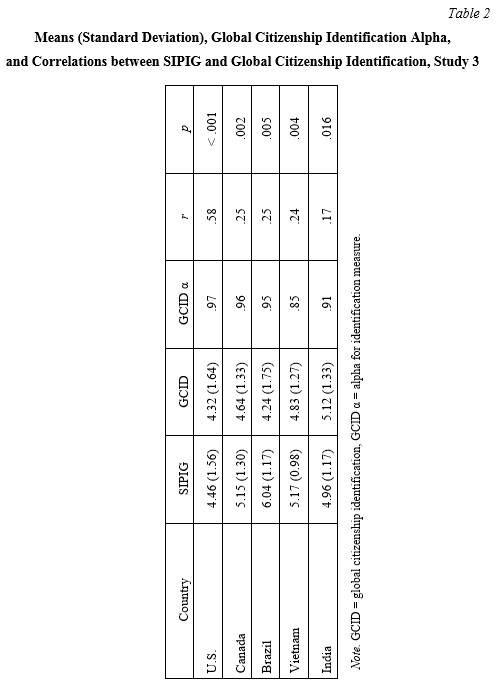

The SIPIG and global citizenship identification measures were identical to Study 1 (see Table 2 for means and alphas).

Results and Discussion

To examine the association between SIPIG and global citizenship identification we conducted correlations by country. As shown in Table 2, the samples from the U.S., Canada, Brazil, Vietnam, and India all showed positive and significant associations. Although the strength of the relationship varied, there was a consistent pattern of positive association in all samples, speaking to the generalizability of the relationship.

Having established both the validity and reliability of the SIPIG and having shown the association between perceived impact of globalization and global citizenship over time and across cultures, we next examined the role of the SIPIG in a model of the antecedents and outcomes global citizenship identification.

Study 4

The purpose of Study 4 was to examine the association between the SIPIG and a model of antecedents and outcomes of global citizenship identification developed in prior research (Reysen and Katzarska-Miller 2013). Studies 1 and 3 found that perceived impact of globalization was positively associated with global citizenship identification. In the present study we examined whether this association is mediated through perceptions of one's normative environment and global awareness and whether the SIPIG indirectly predicts prosocial values. As shown in Study 1, individuals who perceived an impact of globalization engaged with others in one's normative environment. We suggest that others in one's normative environment are likely to hold a positive attitude toward globalization and prescribe a global citizen identity. Also, shown in Study 1, individuals who perceived an impact of globalization also perceived themselves to be knowledgeable about the world. Thus, we expect that the SIPIG will predict global citizenship identification through one's normative environment and global awareness.

Method. Participants and Procedure

Participants (N = 902, 75.1 per cent female, 0.3 per cent other; Mage = 20.99, SD = 4.84) included undergraduate students at Texas A&M University-Commerce participating for extra credit or course credit toward a psychology class. Participants completed the SIPIG and antecedents, identification, and outcomes of global citizenship. All items used a 7-point Likert-type response scale, from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree.

Materials

SIPIG. The single-item measure of perceived impact of globalization was identical to Study 1.

Global citizenship model measures. To assess the antecedents, identification, and outcomes of global citizenship, we adopted measures from prior research (Reysen and Katzarska-Miller 2013; Reysen, Larey and Katzarska-Miller 2012). Four items (e.g., ‘If I called myself a global citizen most people who are important to me would approve’) assessed the perception that others in one's normative environment prescribe a global citizen identity. Four items (e.g., ‘I believe that I am connected to people in other countries, and my actions can affect them’) measured participants' perception that they were interconnected with others and knowledge of the world. Two items (e.g., ‘I strongly identify with global citizens’) assessed global citizenship identification. Two items (e.g., ‘I am able to empathize with people from other countries’) assessed intergroup empathy. Two items (e.g., ‘I would like to join groups that emphasize getting to know people from different countries’) assessed valuing diversity. Two items (e.g., ‘Those countries that are well off should help people in countries who are less fortunate’) measured endorsement of social justice beliefs. Two items (e.g., ‘Natural resources should be used primarily to provide for basic needs rather than material wealth’) assessed environmental sustainability. Two items (e.g., ‘If I could, I would dedicate my life to helping others no matter what country they are from’) assessed intergroup helping. Lastly, two items (e.g., ‘Being actively involved in global issues is my responsibility’) assessed a felt responsibility to act for the betterment of the world (see Table 3 for alphas).

Results and Discussion

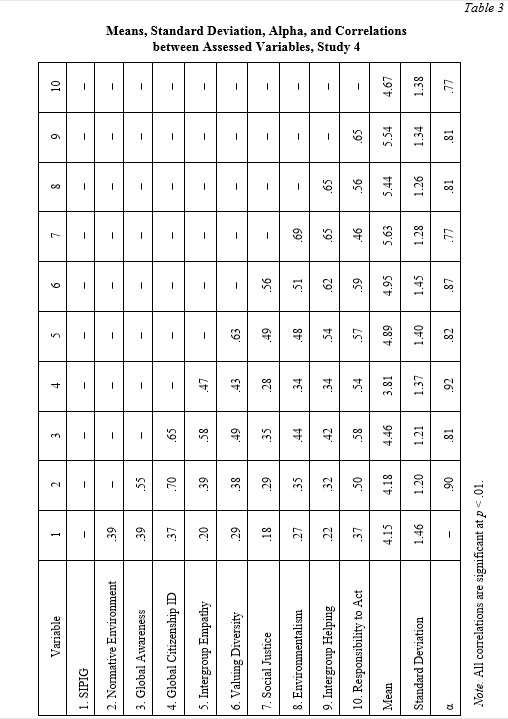

As a preliminary analysis we examined the correlations between the assessed variables. As shown in Table 3, the SIPIG was positively correlated with the antecedents, identification, and outcomes of global citizenship identification. To test the influence of the SIPIG on the antecedents, identification, and outcomes of global citizenship, we conducted a structural equation model using Amos 19 (bias-corrected bootstrapping, 5,000 iterations, 95 per cent confidence intervals). Due to the related nature of the prosocial values to one another (and the antecedents to one another), the disturbance terms for these sets of variables were allowed to covary. Identical to Reysen and Katzarska-Miller (2013), the error terms of two global awareness items were also allowed to covary. The predicted model fit the data modestly well, χ2(204) = 1131.61, p < .001; RMSEA = .071, 90 per cent CI [.067, .075], NFI = .919, CFI = .932.

As shown in Fig. 1, the SIPIG predicted greater normative environment (β = .42, p < .001, 95 per cent CI [.347, .434]) and global awareness (β = .41, p < .001, CI [.335, .479]). Normative environment (β = .53, p < .001, CI [.433, .614]) and global awareness (β = .40, p < .001, CI [.295, .504]) predicted global citizenship identification. Global citizenship identification predicted intergroup empathy (β = .58, p < .001, CI [.518, .643]), valuing diversity (β = .50, p < .001, CI [.429, .565]), social justice (β = .36, p < .001, CI [.276, .435]), environmental sustainability (β = .42, p < .001, CI [.354, .492]), intergroup helping (β = .39, p < .001, CI [.321, .461]), and felt responsibility to act (β = .68, p < .001, CI [.616, .741]).

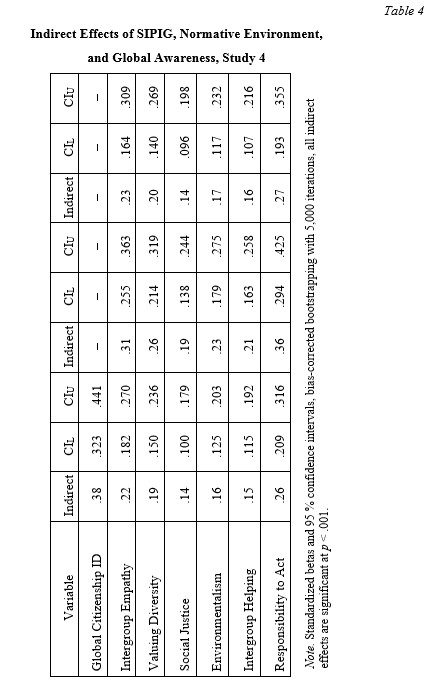

The indirect effect of SIPIG was reliably mediated by normative environment and global awareness on global citizenship identification (see Table 4 for standardized betas of indirect effects and 95 per cent bias-corrected confidence intervals; all indirect effects were significant at p < .001 two-tailed). The perception that one's life is impacted by globalization also significantly predicted greater prosocial values through normative environment, global awareness, and global citizenship identification. Normative environment and global awareness on prosocial values was reliably mediated by global citizenship identification.

General Discussion

The purposes of the present research were to examine the initial validity and reliability of the SIPIG and the association with global citizenship identification. Study 1 showed initial convergent validity for the SIPIG with positive associations globalization related measures and divergent validity with a non-significant association with social desirability. Study 2 showed adequate test-retest reliability for the measure. As predicted, Studies 1, 3, and 4 showed a consistent pattern of positive association between the SIPIG and global citizenship identification across samples, including four non-U.S. samples. The SIPIG was also shown to predict the model of antecedents and outcomes of global citizenship identification. Together, the results support the close connection between engagement with globalization and identification with global citizens.

Globalization has long been theorized (e.g., Arnett 2002) and tested (e.g., Grimalda et al. 2015) with respect to its impact on global identity. Specifically, greater engagement with globalization (e.g., foreign media, friends in other countries) affords individuals a global identity, which connects them to others worldwide. Although the association between globalization at a country level was not significantly associated with global identity (Ariely 2018), at the person level researchers have found that the more individuals perceive themselves as impacted by globalization, the more they identify with the more inclusive global identity (Der-Karabetian and Alfaro 2015; Der-Karabetian et al. 2014; Grimalda et al. 2015). Furthermore, researchers have found this association in a variety of samples worldwide. In the present research we examined the association between perceived impact of globalization and global citizenship identity. The results supported prior studies, with positive associations in the U.S. and in non-U.S. samples. Furthermore, perceived impact of globalization predicted Reysen and Katzarska-Miller's (2013) model of antecedents and outcomes of globalization. The more individuals engage with globalization, the more they view valued others as prescribing the identity and the more they perceive themselves as globally aware, identify with global citizens, and endorse prosocial values and behaviors.

Although not the main focus of the present research, we also provided researchers with a valid and reliable single-item measure of perceived impact of globalization. Much of the prior research within social sciences focuses on perceptions of globalization as positive or negative (e.g., Chen et al. 2016; Das et al. 2013). We constructed the SIPIG to be face valid and to omit reference to the opinion of the favorability of globalization. Higher scores on the SIPIG were related to the consumption of foreign media, interacting with individuals outside the US, and knowledge of the world and international institutions. Furthermore, the results of Study 1 showed that, at least for U.S. participants, the SIPIG was correlated with global openness, having a positive attitude toward globalization, and desire to engage with and learn about other cultures (i.e., multicultural acquisition). The SIPIG is useful for researchers who are conducting large surveys in which space for longer measures are not optional or wish to avoid participant fatigue.

The present research is not without its limitations. First, the present research was correlational in nature. Due to this limitation we are unable to make causal claims regarding engagement or impact of globalization and global citizenship identification. Indeed, individuals may identify as global citizens and then seek out engagement with international media and contact with individuals outside one's country. Second, as with all single-item measures, the SIPIG likely has lower reliability than longer multi-item measures. However, for researchers who are limited for space in a study, the SIPIG is a viable alternative to longer measures. Third, we found that the SIPIG was associated with measures reflecting a positive opinion of globalization. This may differ in other cultural spaces. Future researchers may examine whether the SIPIG is associated with positive globalization in contexts in which there is greater Westernization occurs due to globalization.

To conclude, we examined the association between the perceived impact of globalization and global citizenship identification. Consistent with past research, greater perceived impact of globalization was related to greater identification with global citizens in samples from the U.S., Canada, Brazil, Vietnam, and India. Furthermore, the perceived impact of globalization predicted antecedents and outcomes of global citizenship identification. Additionally, we constructed and provided initial validity and reliability for a single-item measure of perceived impact of globalization. Such a measure will aid researchers conducting cross-national studies in which space on a survey is limited. As globalization and the interconnectedness of the world continues to intensify, more research examining the outcomes of psychological phenomenon is needed.

REFERENCES

Ariely, G. 2017. Global Identification, Xenophobia and Globalisation: A Cross-National Exploration. International Journal of Psychology 52: 87–96.

Ariely, G. 2018. Globalization and Global Identification: A Comparative Multilevel Analysis. National Identities 20: 125–141.

Arnett, J. J. 2002. The Psychology of Globalization. American Psychologist 57: 774–783.

Ashiabi, G. S., and Hasanen, M. 2012. A Measure of Social of Globalization: Factor Analytic and Substantial Validity Assessment Using a Sample of Young Adult Kuwaitis. American Academic and Scholarly Research Journal 4: 9–20.

Buchan, N. R., Brewer, M. B., Grimalda, G., Wilson, R. K., Fatas, E., and Foddy, M. 2011. Global Social Identity and Global Cooperation. Psychological Science 22: 821–828.

Buchan, N. R., Fatas, E., and Grimialda, G. 2012. Connectivity and Cooperation. In Bolton, G. E., and Croson, T. A. (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Economic Conflict Resolution, (pp. 151–181). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Buchan, N. R., Grimalda, G., Wilson, R., Brewer, M., Fatas, E., and Foddy, M. 2009. Globalization and Human Cooperation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106: 4138–4142.

Chen, S. X., Lam, B. C. P., Hui, B. P. H., Ng, J. C. K., Mak, W. W. S., Guan, Y., Buchtel, E. E., Tang, W. C. S., and Lau, V. C. Y. 2016. Conceptualizing Psychological Processes in Response to Globalization: Components, Antecedents, and Consequences of Global Orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 110: 302–331.

Das, A., Hui, P. P., and Das, S. S. 2013. Changing Student Attitudes Towards Globalization: A Study On The Influence of International Business Courses in Qatar and Hong Kong. Journal of Knowledge Globalization 6: 23–46.

Der-Karabetian, A., and Alfaro, M. 2015. Psychological Predictors of Sustainable Behavior in College Samples from the United States, Brazil and the Netherlands. American International Journal of Social Science 4: 29–39.

Der-Karabetian, A., Cao, Y., and Alfaro, M. 2014. Sustainable Behavior, Perceived Globalization Impact, World-Mindedness, Identity, and Perceived Risk in College Samples from the United States, China, and Taiwan. Ecopsychology 6: 218–233.

Gelfand, M. J., Lyons, S. L., and Lun, J. 2011. Toward a Psychological Science of Globalization. Journal of Social Issues 67: 841–853.

Grimalda, G., Buchan, N., and Brewer, M. 2015. Globalization, Social Identity, and Cooperation: An Experimental Analysis of Their Linkages and Effects. Global Cooperation Research Papers. URL: https://duepublico.uni-due.de/servlets/DerivateServlet/ Derivate-39516/Grimalda_Buchan_Brewer_Globalization_2198_0411_GCRP_10.pdf

Hannerz, U. 1992. Cultural Complexity: Studies in the Social Organization of Meaning. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Kapoor, B., and Tomar, A. 2017. Psycho-social Implications of Globalization: An Opportunity-Based Perspective. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology 8: 196–199.

Lee, F. L. F., He, Z., Lee, C.-C., Lin, W.-Y., and Yao, M. 2009. The Attitudes of Urban Chinese towards Globalization: A Survey Study of Media Influence. Pacific Affairs 82: 211–230.

Lee, F. L. F., He, Z., Lee, C.-C., Lin, W., and Yao, M. Z. 2012. Globalization and People's Interest in Foreign Affairs: A Comparative Survey in Hong Kong and Taipei. The International Communication Gazette 74: 221–239.

Melluish, S. 2014. Globalization, Culture and Psychology. International Review of Psychiatry 26: 538–543.

Pieterse, J. N. 2009. Globalization and Culture: Global Mélange. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Postmes, T., Haslam, S. A., and Jans, L. 2013. A Single-Item Measure of Social Identification: Reliability, Validity, and Utility. British Journal of Social Psychology 52: 597–617.

Reysen, S., and Katzarska-Miller, I. 2013. A Model of Global Citizenship: Antecedents and Outcomes. International Journal of Psychology 48: 858–870.

Reysen, S., and Katzarska-Miller, I. 2017. Superordinate and Subgroup Identities as Predictors of Peace and Conflict: The Unique Content of Global Citizenship Identity. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 23: 405–415.

Reysen, S., and Katzarska-Miller, I. 2018. The Psychology of Global Citizenship: A Review of Theory and Research. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Reysen, S., Larey, L. W., and Katzarska-Miller, I. 2012. College Course Curriculum and Global Citizenship. International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning 4: 27–39.

Reysen, S., Pierce, L., Mazambani, G., Mohebpour, I., Puryear, C., Snider, J. S., Gibson, S., and Blake, M. E. 2014. Construction and Initial Validation of a Dictionary for Global Citizen Linguistic Markers. International Journal of Cyber Behavior, Psychology and Learning 4: 1–15.

Strahan, R., and Gerbasi, K. C. 1972. Short, Homogeneous Versions of the Marlow-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology 28: 191–193.

Suh, T., and Kwon, I.-W. 2002. Globalization and Reluctant Buyers. International Marketing Review 19: 663–680.

Suh, T., and Smith, K. H. 2008. Attitude toward Globalization and Country-Of-Origin Evaluations: Toward a Dynamic Theory. Journal of Global Marketing 21: 127–139.

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. 1979. An integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In Austin, W., and Worchel, S. (eds.), The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (pp. 33–47). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., and Wetherell, M. 1987. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.