Cross-Cultural Analysis of Prototypes of Courtship Processes: Turkey, the United States, Lithuania, and Spain

Journal: Journal of Globalization Studies. Volume 11, Number 2 / November 2020

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/jogs/2020.02.07

This study provides an emic, ethnographic and cross-cultural view of courtship practices in the ‘modern’ world. There are limits to our ability to generalize our conclusions to posit a global process. As such this study is suggestive of a larger movement towards new forms of courtship that favor individual autonomy, the pursuit to satisfy personal desires, even at the expense of interpersonal interests. Ilouz and Finkleman (2009) referred to this shift as a move from a ‘premodern modal configurations’ to a ‘modern modal configuration’ of love and desire. Our findings support the theoretical and interview data of the above study and work by many other researchers (e.g., Giddens 2000; Ilouz 2018, 2012; Jankowiak 2008; Munck et al. 2016; Regnerus 2017). Consequently, we have confidence that the trajectory from ‘traditional’ to ‘modern’ courtship processes is a global process. Giddens observed that sex, as a result of contraceptives, has become ‘fully autonomous’ and become a kind of ‘art form’ (Giddens, 1981: 27). Regnerus (2017) builds on Giddens' work by showing how sex, love, and marriage have separated from each other, to the extent that sex is construed as an independent feature of the individual and therefore not part of a coupled, interdependent, construct such as love or family. Sex, as Regnerus writes, has become ‘the malleable property of the individual’ (Ibid.: 7). As our study supports these positions we have confidence that our findings, if extended across more cultures would not be substantially different, only more refined.

Keywords: courtship process, sequence analysis, prototype analysis, cross-cultural study.

Ines Gil Torras, European University Institute more

Victor de Munck, Vilnius University more

Theory

The study is divided into three related themes and claims. Each courtship experience is unique – a wide range of practices are feasible; even so one can discern cultural practices that vary along a limited array of real-world events. The events constitute the main series of events of courtship process in the four cultures studied in the context of autonomous mate selection. Things are different in arranged marriage systems. Yet, it appears that autonomous mate selection is everywhere replacing arranged marriage practices. Second, we will show that there are prototypical models of modern and traditional courtship processes. The prototype may not be the most frequently used process, but it is the most preferred model. Third, we will describe and explain the mechanisms underlying the shift to what we believe is the modern prototypical model of courtship.

Some of the defining properties of courtship are: it is a unique institution in that it is an institution without an organization and it is created in an ad hoc way by the couple themselves (Taylor 1947); it has value in itself (e.g., love; satisfying desires) as well as a means to an end (i.e. marriage, family); it is a process that has an identifiable beginning (i.e., initial attraction) and end (i.e. marriage); it is socially recognized and sanctioned; courtship proffers, in itself, an achieved status to the couple that they themselves recognize; and society places constraints on the process and participates in shaping the courtship sequence (Stanley et al. 2010; Taylor 1947).1

We view the courtship process as comprised of a sequence of events that increasingly ‘fuse’ the couple together through the psychological process of ‘dedication’ and the promulgation of social ‘constraints’ (Cuffari, Clare E. 2017: 107; Stanley et al. 2010: 3). The idea of fusion is more or less explicit in most of the writings on love and courtship but is not stated as such. We take this term from the works of Whitehouse (Whitehouse 2004, 1995) and Whitehouse and Lanman (2014) who write about fusion as a product of an ‘imaging mode of religiosity’ via rituals. As the rituals of human courtship are largely agented and without an external organizational force to directly prescribe behaviors, we substitute continued acts of dedication to each other as the psychological mechanism for fusion and the idea of ‘social constraints’ as the social mechanism for fusion.

Theoretically, the notion of courtship as social

institution that consists of a fusion process constituted of complementary or

dual psychological and social mechanism provides a cultural construction view

of courtship. We accept this perspective as one half of our theoretical

perspective. However, we also claim for autonomous mate selection (a) that

universal similarities are present in all courtship process; (b) these features

are rooted in long-term evolutionary adaptations made by our hominid ancestors;

and

(c) the variability in even sequencing of the courtship process reflects the ‘pre-modern’,

‘modern’ and ‘transitional’ modalities described by Ilouz and Finlkeman (2009).

Methods: Events and Sequences (based on U.S. Data)

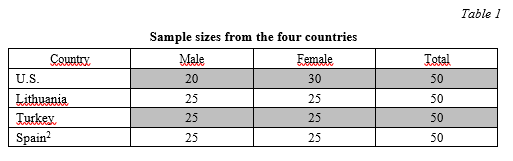

We have sufficient data from four national cultures: the U.S., Lithuania, Spain, and Turkey. All the samples were of adults between the ages of 18 and 55; the average age of the respondents is between 25 and 27 for each of the four samples. We conducted cross tabs to discover if there were significant differences within and between samples based on sex or age. The results supported the null hypothesis; so the following analysis considers these four samples as national samples.

None of the data were collected in the classroom, but outside through recruiting young adults in public spaces and online. The data in the U.S. was collected by various research assistants as well as the author, the data in Lithuania was exclusively collected by the author; the data on Turkey was collected by a U.S. anthropology student who lived in Turkey for a year teaching ESL. The material from Spain was primarily collected on-line by the co-author (Gil-Torras). The sample sizes and gender distribution are as follows.

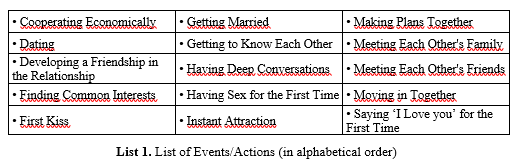

The initial work for

this project was conducted solely with informants from New York City and from a

semi-rural area some 100 miles northwest of the City. From a relatively

thorough and exhaustive study of survey and interview data conducted with 985

individuals we identified 15 significant events in the courtship process. We

decided to validate these events by asking a new sample of informants to

describe, ‘the typical process by which your peers or people in your culture

fall in love and eventually get married?’ These

interviews were structured in such a way as to elicit both sequence (through

such prompts as ‘what typically happens next?’) and an elaboration on the

specific time frames (by asking what emotions, events, and behaviors would be

typical of that time frame). From the above methods we feel confident

that the list of events below signifies the main events of a full courtship

process.

A research limitation is that we did not conduct a similar search for events in the other three countries of this study. However, not one of respondents from those countries suggested additional significant events when asked nor did anyone indicate that events listed did not comprise their experience of the courtship process.

The above terms were individually written on index cards and new informants were asked to place these cards in any order they wished based on (a) what they considered the typical pattern for their peers, (b) what they considered the preferred pattern for themselves; and (c) what was the actual pattern for their most successful courtship. A typical slice of the interviews in the U.S. can be seen in the following slide (Fig. 1. Slide of a portion of the event-emotion courtship process for one informant).

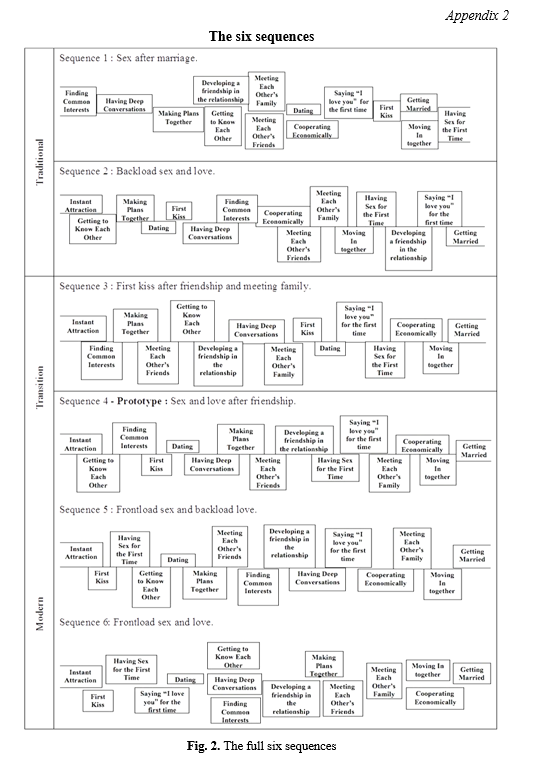

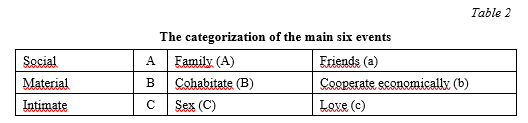

In order to test whether this was the prototypical courtship pattern, five different sequences were developed on the basis of changing the positions of various events.

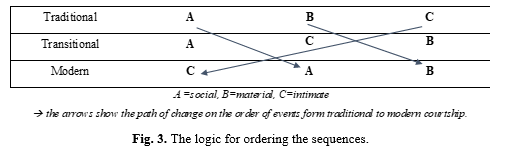

Based on the analysis of the first sample used to obtain the 15 events mentioned before, six of these events were considered of special relevance: ‘meeting each other's family and friends’; ‘cohabitation’; ‘economic cooperation’; ‘having sex for the first time’; and ‘saying I love you for the first time.’ The frequency of appearance of those events in the commentaries of the survey confirms the relevance of these six events. We categorized these six events in three groups (social, material, and intimate) and ordered the six sequences in terms of similarity in order to make easier the comparison between sequences and countries.

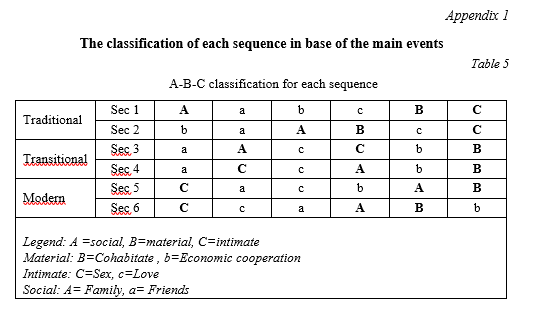

Table 2 presents the classification of events using an A-B-C system (in capital letters – the main event for each category; in lower case – less significant events).

Based on this classification, the general rule to

organize the six sequences is presented in Figure 3. We characterize the

resultant classification of sequences as traditional, transitional and modern

since these patterns are similar to transitional changes described in Ilouz and

Finkelman (2009).

Figure 3 presents the most basic logic followed for ordering the sequences, Sequences 1 and 2 follow a general logic of first social events, then the material ones, and finally the intimate ones; Sequences 3 and 4 (the prototype) follow a general order of first social, then intimate and last material events; and in Sequences 5 and 6 there appear the intimate events, followed by the social events and last, the material ones.

The main goal of this classification is to help

the reader to obtain a general idea of the location of each sequence just by

looking at its number, for example: Sequence 2 is more similar to Sequence 1

than it is to Sequence 5, and Sequence 6 is more ‘modern’ (intimate events

appear earlier) than Sequence 3. One should note here that this figure

generalizes the differences between sequences on pairs (1 and 2; 3 and 4; 5 and

6),

the order of sequences that we present takes into account the nuances between

pairs, these are captured with position of appearance of secondary events

(a-b-c in Table 2). Appendix 1 shows the A-B-C classification for each sequence

including the less significant events.

The six complete sequences are shown in Appendix 2, but in order to have a simpler picture of each sequence for its analysis, we provide a brief description of each of them.

Sequence 1: has first kiss and saying ‘I love you’ just prior to marriage and sex after marriage. This is the ‘traditional’ or ‘staunchly religious’ sequence.

Sequence 2: has ‘sex’ prior to the ‘declaration of love’ and both coming before ‘marriage’, but after social and material events.

Sequence 3: is close to the ‘traditional’ model since the social events (family and friends) and friendship come first; first kiss, dating, love and sex are ‘backloaded’, but they come just before marriage, and a declaration of love comes prior to sex.

Sequence 4: the presumed U.S. prototype, has ‘sex’ come sometime after becoming ‘friends’ and right afterwards there is a ‘declaration of love’ followed by ‘meeting family’, ‘cooperating economically’ and eventually ‘moving in’.

Sequence 5: places ‘having sex’ at the front of the sequence (referred to henceforth as ‘front-loading’) since it comes almost immediately, but decouples it from ‘declaring love’ which comes toward the end, after meeting friends and before meeting family.

Sequence 6: frontloads both ‘sex’ and ‘declaring love’. It is opposite of Sequence 5 by coupling sex and declaration of love suggesting that love is also temporally malleable.

Method 2: Comparing Courtship Sequences Within and Between Cultures

Informants in the four countries were given these six sequences and asked three questions: (1) ‘Please, rate this sequence according to likelihood of its occurrence among your peers?’; (2) ‘Could you please briefly explain what is typical or atypical about this sequence in the context of American/Lithuanian/Spanish/Turkish culture?’3; and (3) ‘Which one of these sequences best fits your most recent courtship experience? If none of these apply, please tell us which one is the closest, and what you would have to change to make it fit?’ The courtship sequences were not translated in Turkish or Lithuanian, largely because we gave them to young adults who were proficient in English; all could read and speak English well enough to evaluate these in English. In the case of Spain, the entire survey was translated to Spanish, therefore the comments showed in this document have been translated into English.

The number of informants for all countries was 50 with a relatively equal sex distribution. We had the informants rate each of the six sequences on the following scale: (1) very unlikely; (2) Not likely; (3) possible; (4) likely; and (5) almost always. They were then asked to comment on their answers to each of these. The entire process took about 45 minutes per informant.

Analysis of the Data

Our analysis proceeds in three stages which can be viewed as different levels of induction, that is making conclusion at different levels of generalizability based on our empirical findings. The more generalizable or the greater the inferential leap between results and analysis, the less confident we are about the reach of our claim. As the leap from data to analysis to claims about the reach of the analysis increases, the less confidence one can have in veridicity or reliableness and validity of the claim. Nevertheless, the purpose is to show where the data leads and to be able to forecast what the future might look like if it continues along the trajectories we have discovered. With this in mind we begin our analysis of the data. We have divided our inductive analysis into three levels of analysis each representing a different reach or scale.

Micro-level of Analysis: What the Data Describes

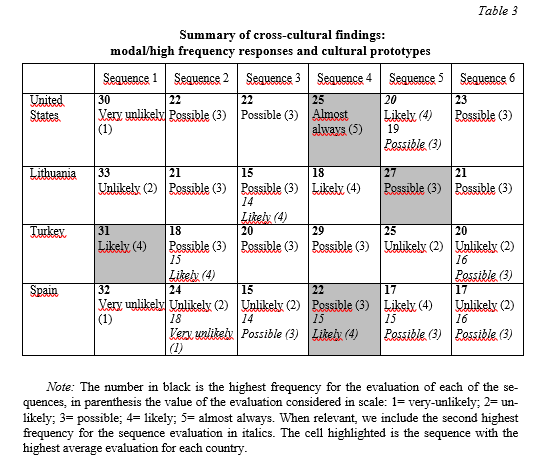

Our basic findings are summarized in Table 1 below (note: the six sequences are in Appendix 2).

While the modal courtship sequence varies across cultures, Sequence 4 is the only sequence for all four cultures which has a solid consensus that it is either ‘possible’, ‘likely’ or ‘almost always.’ It is the sequence that peers seek to emulate. This sequence centers around the development of friendship after which there is sex and love one after the other. Yet, we note that it also seems to be a sort of transitional sequence between traditional models and ‘high modern’ models that reflect Giddens' assertion that, for the first time in at least Western history, sex has been liberated from love in coupled relationships. That is, couples can have long-term culturally acceptable relationships in which the love relationship is sexually open, or sex is the primary reason for the relationship.

For the Lithuanians, Sequence 5 is the modal

sequence and reflects this high modern model of courtship by frontloading sex

and backloading love and parental involvement. That means that the declaration

of love comes many steps after sex, which happens at the beginning of the

relationship. Sequence 6 also frontloads sex, but couples it with a declaration

of love. The main distinction between the U.S. and Lithuanian sequences appear

to be the importance of friendship for the U.S. and the prominence of sex as an

initiating trigger to the development of the courtship process for Lithuanians.

For the Turkish sample the modal sequence was Sequence 1 in which sex happens

after marriage. This interestingly enough is the least likely sequence for both

the U.S. and Lithuanians. Sequence 5, the Lithuanian modal sequence

front-loading sex and decoupling it from love, is the least likely sequence for

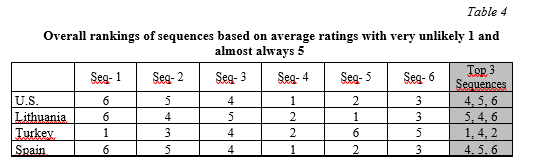

the Turkish sample. Overall rankings of the sequences are displayed in Table 4.

The purpose here is to see a larger pattern to discern how prototypes function

in terms of their extensions to those patterns that are reasonable/feasible

fits with the prototypes as presented above.

This table supports the findings in Table 1 and adds some context. The most obvious thing to note is that Sequence 4, the sequence which frontloads developing a relationship prior to sex and a declaration of love is ranked second in Lithuania and Turkey and is by far the most popular sequence in all three countries. For the United States and Spain the second most popular sequence is Sequence 5, this is Lithuania’s most common sequence, in which sex occurs at the beginning of the relationship and is unhooked from love which is declared after friendship. The sequence 6, which appear as the third most common sequence for United States, Spain and Lithuania, not only sex but love is also at the front. Thus, the Lithuanian modal sequence is considered a feasible sequence for peers to follow by the Spanish and the U.S. samples, but not by the Turkish sample. For the Lithuanian sample the two sequences that frontload sex are ranked first and third, respectively. The importance of the prototypical sequence (Seq-4) as ranked second is that it shows the effect that the ‘declaration of love’ has on choice of sequence, since the only difference between Sequence 5 and 6 is that the latter frontloads love. It would seem that informants were not uneasy about frontloading sex, but they were uneasy about frontloading love. The U.S. ‘model’ is one also adopted by the Lithuanians. The main difference between the Lithuanians and U.S. courtship process seems to be that the Lithuanians recognize sex, by itself, as an important factor at the beginning of a relationship. However, such a recognition is not uncommon among the U.S. conception of courtship given that Sequence 5 (this is the Lithuanian prototype which frontloads sex and backloads love) is the second ranked sequence for U.S. informants. Spain shows the same ranking order as the US, preferring the prototype and then the sequences that frontload sex and backloads love.

The Turkish sample considers their peers not to have sex until after marriage; however friendship, first kiss, and a declaration of love are understood to occur prior to marriage. A problem here may be that we used events and sequences initially derived from the U.S. research. A second conundrum with the Turkish sample is that, except for Sequence 5, all other sequences are mostly possible or probable. This implies a bifurcated or perhaps emerging alternative prototypical courtship process stemming from the West. In this case it would seem that this process reflects cultural diffusion of the modern courtship process from the Western models.

Meso-Level of Analysis

We now take into account what informants report about the various models. We consider this a meso-level because we interpret from their own (microlevel) statement the underlying reasons for their responses to the sequences. This analysis provides the rationale for the order of each sequence, but not for the content or events.

We begin with the U.S. responses. Due to space limitations we will only present informant commentary and discuss three pertinent sequences: the modal, the second most commonly chosen and the sequence deemed ‘most unlikely’ for each culture. We provide what we identified as typical comments by informants. None of the comments below were idiosyncratic (mentioned only once) and all expressed a shared sensibility among informants.

U.S. Commentaries

Sequence 1: sex after marriage

1. I still know people who would like to do it like this.

2. It is a silly sequence all in all.

3. Never happens.

4. There are some that might adhere to this, in more conservative cases, but most of the people I know would not.

Sequence 4: the prototype sequence for U.S.

1. This is the most probable of all the sequences. My only question would be if the friendship started to develop earlier.

2. I think this one is the most normal of the ones I've seen.

3. This seems pretty reasonable, but I tend to develop a relationship or friendship earlier.

4. This situation is typical of a relationship in U.S. culture. Many of the events in the beginning of the sequence are events which may happen very quickly in a relationship.

Sequence 5: A high modern sequence (sex is frontloaded, love backloaded)

1. All of the emotional, developing friendship, finding commonalities, having deep conversations and making plans seem late, and having sex and a first kiss are really soon, without much more than instant attraction.

2. Slutty.

3. When people hook up so quick, it doesn't work out.

4. It sounds like a one-night stand extended.

The general consensus by the U.S. informants is that Sequence 1 is rare and even ‘silly’. For Sequence 4, the quotes indicated that it was ‘the most normal’ of the sequences. Many informants thought that friendship might come earlier in the relationship. De Munck (2019), de Munck and Kornenfeld (2016), Berscheid (2010) and Regan (2017) have also emphasized the importance of friendship in American love relationships. Yet few people have actually studied friendship as an integral part of love relationships. Sequence 5 suggests that sex can happen quickly, but it is not typically thought to lead to a long-term relationship. Sex early-on is typically considered a bad long-term strategy and indicative of a short-term relationship. This emic perspective that sex early on is considered a bad strategy for the development of a long-term relationship is also identified by Regnerus (2017), Bogle (2007) and Garcia et al. (2012). Most saw Sequence 5 as possible or probable (39/50) because it fits the model of the ‘hook up culture’ that is said to be ‘normative’ in US colleges (Bogle 2008; Kuperberg and Padgett 2017; Wade 2017). The ambiguous attitude young adults have with being identified with the hook up culture is expressed in the ‘slutty’ and ‘one-night stand’ comments.

Lithuanian Commentaries

Sequence 1: least likely to happen

1. Such steps like 'first kiss’ is one of the first steps before ‘meeting friends’ and ‘family’. ‘Cooperating economically’ should come after saying ‘I love you.’

2. ‘Sex’ usually comes much earlier. That sequence might have been [common] among older generations, traditional people. Now sex comes somewhere at the beginning.

3. I think ‘first kiss’ and ‘I love you’ really go before ‘meeting parents’. Also most people do not wait until they are married to have sex.

4. ‘Having sex’ for the first time comes much earlier – after having ‘deep conversations!’

Sequence 5: the prototype sequence for Lithuanians

1. Very typical situation for students who live in the dorms.

2. It is the most popular sequence.

3. The beginning is very unlikely.

4. Having sex is too early in this sequence.

Sequence 4: the prototype sequence for the USA

1. Very typical situation among people, who like to project their personal and family life.

2. This sequence is quite possible. With an exception with one thing maybe. Friendship is developed after the marriage.

3. I think it is a good sequence in Lithuanian context.

4. Perfect.

5. Sex is earlier, ‘I love you’ is earlier. Sometimes moving in together is also earlier.

Lithuanians viewed Sequence 1 as the most unlikely to happen. They saw it as ‘traditional’ and perhaps prototypical for ‘older generations.’ They were quick to make changes by moving sex up in the sequence and parents back. This, of course, reflects a high modern sensibility where the individual is ‘in charge’ of his/her own relationship choices and places a high value on autonomy and sexuality. This is further supported in commentaries on Sequence 5, below.

Sequence 5, according to the average rating, is the most prototypical sequence, its status is a bit dubious given the two critical commentaries (which represent the sample). One commentator observed that Sequence 5 was an ‘American’ courtship sequence. It is likely that its high ratings are due to informants thinking that their peers are conducting themselves according to this sequence, but the informant is not. There are other issues underlying this answer. In previous research (De Munck 2005, 2005; de Munck et al. 2011; Munck et al. 2010) it was noted that Lithuanians often view romantic love as transient, false, a kind of temporary liminal state that precedes true love (tikras meiles). Indeed, the term for romantic love is ‘romantishkes meiles’ and the very term ‘romantishkes’ suggests it is a neologism, adapted somewhat recently, perhaps stemming from Western cinema and influence. There is no such strong division in the U.S. since romantic love is combined with ‘being best friends.’ In Lithuania, romantic love typically precedes becoming ‘best friends.’ Further it can be eventually transformed into ‘true love’ under the condition that the couple stays together and becomes best friends.

Many responses indicated that they felt their peers consciously followed an ‘American hook up’ (paskabinti) culture for casual, temporary relationships. Unlike the U.S. sample no one considered having sex early on as ‘slutty’ or as a ‘bad long-term strategy.’ In a sense this sequence describes both the acceptability of promiscuity during young adulthood and developing a long-term love relationship. It also aligns with (Schmitt 2005) epic 48 nation study on sociosexuality ratings (i.e., primarily a measure of promiscuity) in which all three Baltic countries were in the top eight most promiscuous countries, with Lithuania ranked fourth or fifth in the world.

Informants considered Sequence 4 as ‘perfect’ and ‘most likely to happen’ while a similar number of informants wanted to move sex and love up before ‘friendship.’ This suggests that Sequence 4 is conceptually the actual prototype for Lithuanians for true love as a courtship process, though it is not the sequence for failed romantic relationships (which, after all, for young adults are probably the norm) that last for some time but do attain the ultimate goal of these sequences, – ‘marriage.’

For Lithuanians romantic love is not inosculated or bound to a conception of ‘forever’ or even enduring, rather it is a prelude to the more substantive relational stage – ‘true love’. This is quite different from the U.S. data where, clearly, informants perceive friendship as an inextricable and vital property of a romantic love relationship. For the U.S. sample a romantic love relationship without friendship would be akin to what Lee (1973) and Hendrick and Hendrick (1988, 2002) identified as a ‘mania’ love styles. Thus, for Americans there is no conscious division between romantic and true love, whereas for Lithuanians there is.

Turkish Emic Commentaries and Etic Perspectives

Sequence 1: the prototype sequence for Turks

1. Cooperating economically is after getting married.

2. Everything above is very typical and seems really normal to me!

3. There is nothing abnormal for Turkish culture in this sequence.

4. Saying ‘I love you’ is not about culture I think... and in Turkish culture to cooperate economically is not possible. Couples may marry or not and, of course, families rule from the beginning to the end... so this sequence is also abnormal. And one more thing that male after marriage may not be having sex for the first time, but female better be or she may be shot.

Sequence 4: the prototype sequence for U.S. and second most popular for Turks

1. It is useful for the new relationship but old people always say having sex always comes after getting married.

2. I think Turkish culture would not prefer sexual intercourse before getting married. I do not think there is another odd... [placement] ... in the sequence.

3. This sequence is like to occur in our country if we drop out the moving in together.

4. Moving in together and having sex should come after getting married.

5. Having sex for the first time before saying ‘I love you’ is abnormal.

Sequence 5: the least likely to happen in Turkey

1. Having sex for the first time before getting to know each other is abnormal for Turkish culture.

2. Having sex does not happen directly after the first kiss.

3. No way!

4. This is not suitable for Turkish culture.

Sequence 5 is clearly not feasible in Turkey. This sequence is feasible in both Lithuania and the U.S., though in the U.S. the informants referred to Turkish culture to explain why this courtship sequence is just not plausible in Turkey. Sex and, perhaps, declarations of love are strongly sanctioned against by Turkish culture. Thus, as opposed to previous reflections by non-Turks, the respondents took on the role of ‘plural persons’ (Gilbert 2002a, 2002b) who ‘endorsed and enforced’ (Elder-Vass 2012) socio-cultural norms.

While Sequence 1 is labeled as the ‘prototypical sequence’ for Turkey, it seems that many of the events that are listed in the sequence prior to marriage just do not occur and thus the sequence did not feel ‘normal’ to many informants. This point is implied by Comment 1 in which economic cooperation occurs after marriage since there is no ‘moving in’ prior to that. Thus, a better potential prototype sequence would be one that eliminates ‘economic cooperation’ and perhaps ‘making plans together.’ On the other hand, a number of informants agreed that this is a ‘normal’ sequence. It is not clear whether this sequence would also be an emically derived prototype, probably not. However, it is a culturally feasible and appropriate courtship sequence for informants. To obtain a more emically prototypical sequence one might highlight the roles of family and friends, thus suggesting that courtship involves a broader social network of interests than in Lithuania or the United States.

The comments for Sequence 4 point to the problem of having sex prior to marriage, otherwise this is a sequence that seems to resonate among informants. Further sex should follow and never precede a ‘declaration of love.’ Sequence 4 is almost at the same level as Sequence 3 which is the second most popular or acceptable sequence of the six sequences with 33 (66 per cent) considering this possible or probable. Sequence 2 is the sequence most like Sequence 1, except that sex followed by a declaration of love comes just prior to marriage. The frequent ratings of ‘probability’ for this sequence (N = 31) with the absence of any ratings for ‘possible’ suggest that premarital sex does occur, but clandestinely and after parents have put their stamp if not arranged the marriage. We note that the lack of any score that Sequence 4 is probable appears to be solely due to sex and love coming earlier in Sequence 4 than in Sequence 2.

Spanish commentaries

Sequence 1: The less possible

1. Sex after marriage that does not happen anymore.

2. I think it is a very old fashion sequence.

3. Sex after marriage? Love before kissing? Maybe 5 decades ago, today that model is practically unthinkable.

Sequence 4: the U.S. Prototype and the Spanish favorite

1. Perfect sequence.

2. It would be more probable if sex came earlier.

3. Besides the too early kiss, this sequence shows more time needed to meet each other, is more plausible.

4. Realistic.

5. Logic and common.

6. Is what society defines as normal.

7. Is the supposed ‘ideal’ sequence, I think is what movies and TV show us all the time as perfect.

Sequence 5: the second most liked sequence

1. Cooperate economically should happen just after moving in together.

2. Making plans should come after friendship.

3. Again is a relationship based on the desire instead of caring and respect.

4. Many relationships start as one-night stand.

5. A bit fast, but very plausible.

6. Normally the people that have sex before getting to know each other do not end up in wedding. I like it, but sex before knowing each other better does not consolidate the relationship.

7. This sequence goes in line with many relationships of my environment.

8. I think is the most common one.

According to these comments we can see that Spanish informants seem to be in between the Americans and Lithuanians. The Spanish sample viewed Sequence 4 as “most preferred” just as do the Americans. One of the comments associated this sequence with the influence of movies and TV, which can be perceived as the social norm. With a few exceptions, most of the comments classified the sequence as the most ‘likely to occur’, ‘ideal’ and ‘logical.’ A few of the exceptional comments centered on moving sex earlier in the sequence, which make sense as Sequence 5 is the second most liked by the Spanish informants. Yet, even when they rate this sequence almost as probable as Sequence 4, many made negative comments towards early sex, mentioning that early sex does not help to consolidate relationship. The comments also refer to this sequence as an extension form of the ‘hook-up’ culture, referred to previously in the analysis of the US comments (Bogle 2008; Kuperberg and Padgett 2017; Wade 2017). In any case, the Spanish informants considered Sequence 6 as the third favorite, which give us a sense of the relevance of the hook-up culture within the normative construction of relationship. The comments confirm that there is a separation between the conceptualization and meaning of sex and romantic courtship.

3. Macro-Level of Analysis: Idiographic versus Nomothetic Cultural Models

There are clear local cultural differences in informants' conceptions of the cultural prototype for courtship. A problem with the sequences is that they all presume some sort of autonomy in making choices by individuals and that the events listed are salient across cultures. However, an advantage of providing informants with the six sequences and asking them to rate each and to comment on them is that informants are able to both dispute the sequencing of events and to point out which events are either not salient or ‘abnormal.’ This seemed to be a more pertinent factor among the Turkish informants than for the U.S. or Lithuanian informants. On the other hand, many Turkish informants pointed out that the prototypical sequence (i.e., Sequence 1) was for them ‘normal.’ Thus, there is no strong evidence to suggest that a cross-cultural comparison using these sequences is invalid on the grounds that none of the sequences reflect a culturally appropriate courtship sequence.

These sequences serve as possible scripts or guides for various culturally feasible courtship processes. For the Turkish informants two rules can be established: the first, in a successful courtship process sex should always come after a declaration of love; the second, sex should always come after marriage. However, for forward-minded Turks, sex may occur prior to marriage but this is risky, particularly for women. Indeed, as this data was collected in 2012, the evidence suggests that university students in urban areas of Turkey are adopting more Western models of courtship and dating.

What stands out for the USA is the strong division between sex and love. Friendship is a necessary but not sufficient feature of a good romantic love relationship. The relationship is causal in the sense that if one declares love, then it implies that you also view each other as best friends. In contrast, in Lithuania one can declare love without necessarily being best friends or even friends. However, this declaration of love for Lithuanians refers to romantic love which is consciously distinguished from true love. Thus, there may be two kinds of declarations of love in Lithuania: one for romantic love, which emphasizes eros, passion, poetry and playfulness, and another one which is more storgic (calculating) and pragmatic that emphasizes commitment, intimacy and family. Spain seems to be willing to include sexual intercourse earlier in the sequence but at the same time, as in the case of the U.S., they seem to separate sex from love, connecting Sequences 5 and 6 with the prolongation of a hock up or a night stand, and considering that ‘too early sex’ is less likely to conduct to a formal relationship. Yet, they give special value to the placement of friendship and getting to know each other before declaration of love and engaging in the material events of the courtship such as moving in together or cooperate economically.

To return to points broached by the meso-level analysis, it is conjectured that the difference between the U.S. and Lithuanian versions of love and courtship are based on social and historical grounds. During Soviet times, Lithuanian youths belonged to Soviet Youth leagues and each summer youths were compelled to travel to collective farms to work. If one can imagine, without a religious socio-moral penumbra dissuading teenagers from sexual relations, such liminal sites of work camps where boys and girls lived and regularly worked and played together, led to quite a bit of premarital sex. Thus, casual sex was dislodged from a religious foundation and also ‘naturalized’ during these summer labor camps, some distance from home and the surveillance of parents. By reducing the presence and hence authority of parents and religion, young soviet adults could engage in premarital sex without fear of parental or religious recrimination and punishment. We think it is for this reason that foregrounding sex does not trigger any sanctimonious expressions of sinful or ‘slutty’ behavior by the Lithuanian sample when sex is foregrounded. This is not to say that such dispositions are non-existent, but rather that they are not normative.

Second, Lithuanian, Spanish and Turkish schoolchildren tend to stay with their cohorts from year to year, changing teachers not students. This leads to the development of strong friendship ties with one's classmates as they move up the grades in fairly stable cohorts. By contrast, the U.S. classroom composition is very fluid year to year. Each year both teacher and classmates change in composition. In middle school (beginning with the 6th grade) and high school they change from class to class. This leads to extensive weak ties by which one classifies others as ‘friends.’

Given these different social structures and practices, ‘friendship’ is transient and constantly changing in the peer context of public education in the United States, whereas in Lithuania and Turkey one's ‘batch-mates’ remain relatively stable in composition and, as a result, individuals form strong friendship rather than weak friendship ties. Consequently, in love relationships, U.S. couples are quick to call each other ‘best friends’ and work toward developing an enduring friendship relationship. Couples in Lithuania, Spain and Turkey see friendship as a long-term process and as itself an enduring relationship that comes with time. Hence, sex and even romantic love are not so easily attached or associated with friendship in Turkey, Spain or Lithuania as in the United States.

Finally, there may well be a convergence among the three cultures towards Sequence 4 as the prototype that leads to cohabitation or marriage. The ‘hook-up’ culture prevalent in the United States and perhaps also in Lithuania as well as among many other Western young adults suggests that the goal-oriented nature of the courtship sequence may itself not be prototypical of what young adults are seeking (Bauman, 2003; Garcia et al., 2012; Ilouz, 2018, 2012; Wade, 2017). However, the notion of terminal committed coupled relationships has had enough of a history to weather even this turbulent but small storm.

Conclusion

We have discovered the main events that constitute courtship processes when there is autonomous mate selection. From these events we obtained, what we called, the prototypical model, consisting of a sequence of the fifteen main events. We then created five more variations of the prototype by moving the six events of special relevance. These were: ‘meeting each other's family,’ ‘meeting friends.’ ‘cohabitation,’ ‘economic cooperation,’ ‘having sex for the first time,’ and ‘saying I love you for the first time.’ The six sequences were given to informants in four different countries. Only the Turkish sample selected the sequence where sex and the declaration of love come after marriage. The prototypical model was the one that frontloaded events that build up the couple's relationship in terms of intimacy and friendship prior to love and sex. This is best represented by Sequence 4, in which intimacy and friendship are developed prior to love and sex, thereafter one's beloved is introduced to the respective parents. This prototype may also be called the ‘normative model’ because it is not just a cognitive model but a shared and thus culturally normative model with coercive force. The two most ‘traditional’ models foregrounded the authority of family to filter marriage choices, so these contain external constraints on mate selection. In the most modern sequences (Sequences 5 and 6) family is placed in the back end of the sequence while sex is frontloaded.

Our findings corroborate general intuitive understandings of contemporary courtship processes and more specifically, validates exactly the study and prediction of Ilouz and Finkeleman (2009) concerning the rupture between traditional and modern conceptions of self, intimacy and love. We suspect that over time, Sequence 4 will be conceptualized as ‘traditional’ and even the idea of marriage as the end point of a courtship sequence will be considered ‘old fashioned.’ We view our findings as corroborating the general global process of transformation between sex, love, marriage and family in which individuals acquire a greater sense of viewing each of these important nodes in the continuity of our species, as independent of one another.

NOTES

1 The idea of courtship as an institution is developed from the work of Taylor (1947) and that of ‘secure romantic attachment’ from Stanley, Rhoades, and Whitton (2010).

2 For the purpose of this study, in the case of Spain, a random sample of 50 informants was subtracted from the total of 897 surveys obtained from the country. The random sample was obtained using Stata, 25 informants per gender under the conditions of age between 18 and 55, we excluded the non-binary gender informants and migrants. In that way four samples were comparable in their distributions.

3 It was adapted for each country ‘Lithuanian culture,’ ‘Turkish culture,’ and ‘Spanish culture.’

REFERENCES

Bauman, Z. 2003. Liquid Love: On the Frailty of Human Bonds. Cambridge, UK – Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub – Polity Press.

Berscheid, E. 2010. Love in the Fourth Dimension. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 61: 1–25.

Bogle, K. A. 2008. Hooking Up: Sex, Dating, and Relationships on Campus. New York: NYU Press.

Cuffari, C. E., 2017. Friendless Women and the Myth of Male Nonage: Need a Better Science of Love and Sex. In LaChance Adams, S., Davidson, Ch. M., Lundquist, C. R. (eds.), New Philosophies of Sex and Love: Thinking Through Desire (pp. 101–125). New York: Rowman Littlefield.

Elder-Vass, D. 2012. The Reality of Social Construction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Garcia, J. R., Reiber, C., Massey, S. G., Merriwether, A. M. 2012. Sexual Hookup Culture: A Review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 16: 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027911.

Giddens, A. 2000. The Transformation of Intimacy: Sexuality, Love and Eroticism in Modern Societies. Stanford, CA: Stanford Univ. Press.

Giddens, A. 1981. A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism. University of California Press.

Gilbert, M. 2002a. Belief and Acceptance as Features of Groups. Protosociology 16: 35–69.

Gilbert, M. 2002b. Collective Guilt and Collective Guilt Feelings. The Journal of Ethics 6: 115–143.

Hendrick, C., Hendrick, S. S. 1988. Lovers Wear Rose Colored Glasses. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 5(2): 161–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/026540758800500203.

Hendrick, S. S., Hendrick, C. 2002. Linking Romantic Love with Sex: Development of the Perceptions of Love and Sex Scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 19: 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407502193004.

Illouz, E., Finkelman, S. 2009. An Odd and Inseparable Couple: Emotion and Rationality in Partner Selection. Theory Soc. 38: 401–422.

Ilouz, E. 2018. Emotions as Commodities: How Commodities Became Authentic. London: Routledge.

Ilouz, E. 2012. Why Love Hurts: A Sociological Explanation. Polity.

Jankowiak, W. (ed.) 2008. Intimacies: Love and Sex across Cultures. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kuperberg, A., Padgett, J. E. 2017. Partner Meeting Contexts and Risky Behavior in College Students’ Other-Sex and Same-Sex Hookups. J. Sex Res. 54: 55–72.

Lee, J. A. 1973. Colours of Love: An Exploration of the Ways of Loving. 1st edition. Toronto: New Press.

Munck, V. C. de 2005. The Need for Culture (Even if it doesn't Exist): A Lithuanian Example. Liet. Etnologija 33–47.

Munck, V. C. de 2019. Romantic Love in America: Cultural Models of Gay, Straight, and Polyamorous Relationships. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

Munck, V. C. de, Korotayev, A., de Munck, J., Khaltourina, D. 2011. Cross-Cultural Analysis of Models of Romantic Love Among U.S. Residents, Russians, and Lithuanians. Cross-Cult. Res. 45: 128–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397110393313.

Munck, V. C. de, Kronenfeld, D. B. 2016. Romantic Love in the United States: Applying Cultural Models Theory and Methods. SAGE Open 6, 2158244015622797. https:// doi.org/10.1177/2158244015622797.

Munck, V. de, Korotayev, A., Khaltourina, D. 2010. A Comparative Study of the Structure of Love in the U. S. and Russia: Finding a Common Core of Characteristics and National and Gender Differences. Ethnol. Int. J. Cult. Soc. Anthropol. 48: 337–357.

Munck, V. de, Korotayev, A., McGreevey, J. 2016. Romantic Love and Family Organization: A Case for Romantic Love as a Biosocial Universal. Evol. Psychol. 14, 1474704916674211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474704916674211.

Regan, P. C. 2017. The Mating Game: A Primer on Love, Sex, and Marriage. Thousand Oaks, California. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483396934.

Regnerus, M. 2017. Cheap Sex: The Transformation of Men, Marriage, and Monogamy. Oxford University Press.

Schmitt, D. P. 2005. Sociosexuality from Argentina to Zimbabwe: A 48-nation study of sex, culture, and strategies of human mating. Behav. Brain Sci. 28: 247–275. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X05000051.

Stanley, S. M., Rhoades, G. K., Whitton, S. W. 2010. Commitment: Functions, Formation, and the Securing of Romantic Attachment. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2: 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00060.x.

Taylor, C. C. 1947. Sociology and Common Sense. Am. Sociol. Rev. 12, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.2307/2086483.

Wade, L. 2017. American Hookup: The New Culture of Sex on Campus. W. W. Norton & Company.

Whitehouse, H. 2004. Modes of Religiosity: A Cognitive Theory of Religious Transmission, Cognitive Science of Religion Series. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Whitehouse, H. 1995. Inside the Cult: Religious Innovations and Transmission in Papua New Guinea. Oxford Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Whitehouse, H., Lanman, J. A. 2014. The Ties That Bind Us: Ritual, Fusion, and Identification. Curr. Anthropol. 55: 674–695. https://doi.org/10.1086/678698.

APPENDIXES