Testing Tilly: Does War Really Make States?

Journal: Social Evolution & History. Volume 21, Number 1 / March 2022

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/seh/2022.01.07

Though much is written about coercive theories of state formation and the role of war in the formation of the modern territorial state, no comprehensive quantitative test of the theory, made famous by Charles Tilly, that ‘war makes states’ exists. Data collected and analyzed from George Kohn's (2000) Dictionary of Wars and Valerie Bockstette, Areendam Chanda and Louis Putterman's (2002) State Antiquity Index finally brings quantitative support for the argument that ‘war makes states,’ providing insight into the impact of conflict on the ability of groups to form states with strong institutional capacity. The results confirm Tilly's theory: war plays a prominent role in the formation of strong states, though, location and foreign occupation also matter.

Keywords: coercive theories, conflict, state capacity, state formation, war.

Laura D. Young, Georgia Gwinnett College more

INTRODUCTION

In 1992, Charles Tilly published Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990 – 1992. The book introduces a coercive theory of state formation that analyzes the development of the modern territorial state in Western Europe. Tilly's main argument is that war is the driving force that leads to the modern territorial state. His theory, ‘war makes states,’ has gone on to become one of the leading theories of state formation in comparative politics; though, he is, of course, not the only one to make this argument. While much is written about coercive theories of state formation, at least to this author's knowledge, no comprehensive quantitative test of this theory exists. As a result, this paper constructs a dataset from 0 – 1600 CE to test Tilly's theory that the consequences of preparing for and waging war leads to the formation of the modern territorial state. The results add quantitative support for the argument that war really does ‘make states.’1

The relationship between conflict and state formation is important because how the state evolved explains why some states develop institutions with a great deal of capacity while others suffer from a lack of capacity altogether. This, in turn, leads to more probing questions such as why some states failed to establish modern political institutions in places like Iraq, Somalia, and Afghanistan. Moreover, how a state evolved has important consequences regarding its interactions in the international system. A state that controls its territory and has a monopoly over the legitimate use of force, for example, is better equipped to conquer nations lacking these capacities. This difference explains the consequence of various state behaviors in the international environment. Because European states developed many more organized and centralized government structures sooner than Asia and Africa, for example, European states dominated international relations for most of the pre-modern and modern era (Kennedy 1987).

One of the reasons why no one has undertaken a quantitative analysis of Tilly's theory is likely because of the lack of available data. Although several datasets on war in the modern era exist, a comprehensive dataset on wars in the pre-modern era does not. Likewise, because states in their present-day form did not exist in the pre-modern era, accounting for state capacity during this period can be problematic. Fortunately, George Kohn's (2000) Dictionary of Wars and Valerie Bockstette, Areendam Chanda and Louis Putterman's (2002) State Antiquity Index, provide information useful to construct a dataset to test whether conflict led to the modern territorial state.

Unlike Tilly's original theory which focused on Europe, I test the hypotheses in Africa and Asia as well. I argue if war makes states, then we should expect to find that the reason why states failed to form in many parts of Africa prior to colonialism (despite the fact humans existed here millions of years longer than in Europe), for example, is because there was a lack of conflict in this region. The findings confirm the hypothesis. The more conflict a state faces, the more likely it is to develop strong institutional capacity. Those states that faced the least conflict, most often developed the weakest institutions. The results also reveal conflict-prone neighbors can make even peaceful neighbors not engaging in conflict increase their strength to survive.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In Coercion, Capital and European States, AD 990 – 1992, Charles Tilly makes the case that the modern state structure is a consequence of the necessity of waging war. ‘War made the state, and the state made war,’ he argues. Tilly does not disagree with economic and class-based theories2 that argue the internal make-up of states (e.g., how classes are organized) is important regarding the variation in state development. He disagrees, however, that it is the main impetus that created the modern territorial state. Instead, the organization of classes merely affects the way in which rulers extract the means (e.g., taxes, people) necessary to engage in coercive efforts. Further, areas that were capital-intensive rather than coercive never fully developed into states. These areas remained city-states instead. The driving force behind state formation is, therefore, the preparation for and engagement in war. Those rulers that were most effective in concentrating and accumulating the means of coercion created an environment in which states grew (Tilly 1992: 19).

Tilly is not the only one that argues coercive theories explain state formation. Thomas Ertman agrees ‘the territorial state triumphed over other possible political forms [of rule] because of the superior fighting ability which it derived from access to both urban capital and coercive authority over peasant taxpayers and army recruits’ (Ertman 1997: 4). In short, war-making and, most notably, the extraction of capital were the essential elements in the formation and survival of early states. Thus, the stronger the state, the more efficient it is at extracting capital (Acemoglu 2005), and thus, the more successful it is at waging war (Glete 2002; Spruyt 1997).3

Coercive theories suggest several reasons why war leads to states. First, because leaders ‘must administer the lands, goods and people they acquire’ it requires more institutions and a larger bureaucratic organization. Specifically, war ‘builds up an infrastructure of taxation, supply, and administration that requires maintenance of itself.’ Bureaucracies form as a result (Tilly 1992: 20). For example, the ruler's creation of armed forces generates a stronger state structure because it brings with it bureaucratic organization such as treasuries, supply services, and tax bureaus.4 War also helps consolidate power in the governing body because of the collection of capital. The collection of capital is important for a state to wage war successfully. Therefore, those states which created a structure that efficiently extracted capital proved more successful in waging war, and, consequently, consolidating power (Tilly 1992). Members of society deferred to the ruler because they were dependent on the ruler for protection against competing neighbors. This deferral allowed for the strengthening of power in the ruler and provided opportunities for the ruler to structure society so that it could raise taxes as well as establish bureaucratic entities to manage society. Cities, and then eventually states, formed because of the increased ability for the collection of revenue (Tilly 1992).

Another benefit of war is that it helps societies consolidate under one rule much quicker. Specifically, war helps secure a distinct territory which is essential for defining not only the physical boundaries of a state, but also demarcates the people under the state's rule. In addition, war can expand the territory inhabited by villages and tribes into greater areas which not only supports more population, but also greatly expands the power of the up-and-coming state. This distinction helps to further consolidate power and strengthen the state.

Though Tilly's theory applies to the modern state system, war was also an important catalyst in the formation of the premodern state. In fact, the idea that warfare is a modern invention is disproven by exhaustive evidence which ‘shows a continuous use of violence by prehistoric human societies’ (Fukuyama 2011: 73). Interestingly, though, few of these wars resulted in conquest of new territory by the victor. This lack of conquest is likely because, as Francis Fukuyama explains, war can occur for several reasons other than for control of territory. War is also fought spontaneously or for prestige, honor, economic purposes, or revenge. Nevertheless, overwhelming evidence suggests conflict occurred most frequently in antiquity when a society suffered from a large population with scarce resources to support it (Carneiro 1970). This point is important because disputes over territory were unique in that these battles usually resulted in the conquest of land and foreign peoples by the victor. Therefore, unlike other forms of warfare where the acquisition of territory and people did not occur, conquest warfare – spurred by conflict over resources – created conditions that required the creation of institutions with enough capacity to manage the ever-increasing complex society, thus representing the origins and development of the early state (Carneiro 1970).

In sum, when it comes to state formation, coercive theories argue war is essential to the origins and development of the state – whether in the premodern or modern era – since war comes with several benefits which help to consolidate power and strengthen societies. In particular, war fosters the growth of a complex bureaucracy necessary to support the war effort, and it helps consolidate power for the ruler as well as territory. Those societies most efficient at creating these institutions and consolidating power, therefore, develop the strongest states. The absence of war, on the other hand, does not necessarily preclude a state from forming strong institutions, but without war, the need to form strong institutions is less important.

DEFINITIONS, DATA AND RESULTS

State formation is a topic given a lot of attention within comparative politics, and despite the theoretical evidence available to support Tilly's findings regarding the impact of war on the creation of the modern state structure, as mentioned, no quantitative analysis exists to test this theory. This is likely because discussing the formation of states presents many obstacles. How one defines the term ‘state’ or ‘state capacity,’ for example, can vary significantly. In addition, discussing the capacity of a state in a period before the state formed requires an understanding of the evolution of states.

Because ‘scholars, predictably, disagree on exactly what social or cultural “complexity,” or a “civilization,” or a “state,” is,’ there is no universally accepted definition (Wenke 1999: 331). In fact, there are ‘no shortage of competing definitions’ mainly because ‘a definition of the state always depends on distinguishing it from society, and the line between the two is difficult to draw in practice’ (Mitchell 1991: 77). Although less of a problem when examining societies individually, it becomes particularly problematic when attempting cross-country analysis.

The second reason it is so difficult to define a state is because scholars, in particular political scientists, think of a state in very limited terms. Realism, for instance, defines states simply as unitary, rational, and geographically-based actors. Defining power in terms of relative military, economic, and even political capabilities allows for states to have different levels of power (Morgenthau 1948). Unfortunately, this definition lacks the ability to distinguish at what point a group reaches the unitary-rational-geographically-based-actor status. While useful at the international level, it does little to help explain much else about states outside of that arena. In addition, the literature has reduced ‘the state to a subjective system of decision making.’ This view is narrow and idealist because it attempts to divide the state from society with an ‘elusive boundary’ scholars try to ‘fix’ with the right definition. Instead, ‘we need to examine the detailed political processes through which the uncertain yet powerful distinction between state and society is produced’ (Mitchell 1991: 85).

Moreover, common definitions of a state in political science provide little room to think about the state outside of a fully developed stage. In fact, we consider states that do not meet these stringent requirements as ‘failed states’ even though, clearly, some institutions still exist in its place. As Alexander Wenke puts it, ‘Even in our own age, it is difficult to avoid the notions that… simpler societies are incompletely developed, and that all the world's cultures are at various points along a gradient whose apex is the modern Western industrial community’ (1999: 336). Despite acknowledging variation exists when it comes to distinguishing what constitutes a state, it is still problematic to discuss the characteristics of a state such as Germany, or China, or even South Africa a thousand years ago when only individual groups lived in these areas and states in their present-day form clearly did not exist at that time.

Though states did not exist in their present form hundreds or thousands of years ago, this does not mean that the origins of the Germanic people that currently make up the modern-day state of Germany, for example, are not identifiable in some other type of societal structure prior to the modern-day state era. ‘Cultural evolution is not a continuous, cumulative gradual change, in most places “Fits and Starts” better describes it’ (Wenke 1999: 336). In short, states take on many shapes over the course of thousands of years of formation. Thus, to understand this process requires thinking outside the rigid definitions of a state that typically apply only to the modern territorial state.

In addition, focus is often placed on the type of institutions within a state to help explain its formation. This, too, does little to further our knowledge as to why states in Africa failed to develop the capacity of states in Europe. The type or ‘ideology’ or institutions in a state matter, but matter to a much less extent than typically portrayed. An autocratic regime can maintain strong infrastructure, institutions, and internal as well as external military control just like a democratic regime. Likewise, some democracies suffer from a lack of capacity, especially newly transitioning ones. Because state capacity is not dependent upon the type of institutions in place, it is necessary to broaden how we think about states. Without a new way of thinking, research remains blocked in its ability to fully explain the modern state, much less the differentiation in capacity across regions.

With this in mind, and drawing from various disciplines' definitions of ‘state,’ ‘society,’ and ‘civilization,’ I define a ‘state’ as a society with some sort of rituals, traditions, and rules that can differentiate in terms of structural organization, such as levels of hierarchy, as well as capacity to project power both internally and externally. This definition meets most basic assumptions about the various components that make up a state. It also makes it possible to discuss a state throughout different levels across time and space. In other words, reworking the definition of a state to include specific characteristics of differing groups allows us to study the evolution of a particular state during a period when the modern-day version did not exist. Though they do not specifically frame their discussion of state formation in this same way, authors such as James Scott (2009), Francis Fukuyama (2011), Jared Diamond (2009), and Max Weber (1946) explore the evolution of the state, or the lack thereof in Scott's case, in much this same way by starting with the organization of societies in primitive times. Robert J. Wenke likewise defines society in a similar fashion (1999: 332).

It is necessary to note this definition differs from that given to ‘nation.’ Although it defines one characteristic of a state as having some sort of ritual, traditions, and rules, this is not the same as having a shared identity or culture. Though important for state strength, it does not accurately define ‘state.’ As Walker Connor explains, a state is tangible – readily defined and easily quantified. ‘Peru, for illustration, can be defined in an easily conceptualized manner as the territorial-political unit consisting of sixteen million inhabitants of the 514,060 square miles located on the west coast of South America between 69 and 80 west, and 2 and 18, 21 south’ (1978: 300). No mention about the identity of the people in the area is necessary to identify the ‘state.’ Therefore, a state can be thought of as the territory over which a central power makes claim to political power and can demonstrate that power by extracting compliance from inhabitants and recognition of this power over the territory from foreigners and other states.

Nations, on the other hand, are intangible, self-defined, and consist of ‘a psychological bond that joins a people and differentiates it, in the subconscious conviction of its members, from all other people in a most vital way’ (Connor 1978: 300–301). A popular definition in international relations of a nation is that it consists of ‘a social group which shares a common ideology, common institutions and customs, and a sense of homogenetry.’ The group may have a sense of belonging to a particular territory, though certain religious sects also exhibit these same characteristics (Connor 1978: 301–304). International relations scholars have gone to great lengths to differentiate between state and nation. Nevertheless, ‘having defined the nation as an essentially psychological phenomenon,’ scholars still treat the term ‘as fully synonymous with the very different and totally tangible concept of the state’ (Connor 1978: 301).

The merger of these two terms is problematic. Though the more homogenous a society the easier it is for a state to establish institutions with a great deal of capacity, it is not an essential component for state formation. In fact, Connor surveyed 132 states and found that only 12 states, or 9.1 per cent, qualified as nation-states. In ‘this era of immigration and cultural diffusion,’ he cautions, ‘even that figure is probably on the high side’ (1978: 301–304). These two terms must be separated, therefore, so that the inclusion of states at all capacity levels is possible.

The definition adopted in this paper coincides with Tilly's own argument regarding the characteristics of a state. According to him, city-states, empires, theocracies, and many other forms of government above the band or tribal level represent the different levels of statehood that evolved over time. He argues, though each type of state has distinct characteristics to differentiate it as a separate type of political order, they are merely ‘plausible alternatives’ from which elites choose; therefore, all represent one form of a state or another (Tilly 1992: 1–5; see also Connelly 2003; Cooper 2005; Kumar 2010). As long as the organization controls ‘the principal concentrated means of coercion within delimited territories, and exercise[s] priority in some respects over all other organizations acting within the territories’ then, regardless of how homogenized or centralized authority, the political unit is a state (Tilly 1992: 5).

Defining State Capacity

Just as disagreement exists on what constitutes a state, there is little consensus on how to measure the capacity of a state. Some scholars view state capacity in terms of economic and military prowess consistent with the realist and neorealist understanding of relative power capabilities (Mearsheimer 2001; Morganthau 1948; Schweller 1992; Waltz 1979). Others categorize a state's capacity dependent upon its economic and developmental capabilities (Herbst 2000; Migdal 1988; Scott 2009; and Acemoglu 2005). States whose leadership maintains a monopoly over the control of the population through coercive policies and brute force are considered to have the most capacity according to others. Because democratic leaders are often constrained by their constituency, democratic regimes are viewed as lacking the necessary capacity to project power (Johnson 1984; Ikenberry et al. 1996; Katzenstein 1996). Authoritarian regimes, in contrast, enjoy a considerable deal of institutional capacity since leaders can make decisions without fear of backlash from an angry Selectorate (Bueno de Mesquite 2003). For some, a state's capacity is measured by its ability to influence and control the perceptions of others (MacMillan 1978). Along these same lines, the cohesiveness of society can affect the state's level of capacity. ‘Since groups can be mobilized by persuasion as well as coercion, it should be possible to bring and keep members together voluntarily’ (March and Olsen 1989: 12).

Since rituals and symbols create a sense of community which helps unify society and thus, also increase legitimacy, those states with the ability to build a cohesive society also, subsequently, have the most institutional capacity (Desch 1996: 256). Combining definitions that emphasize the scope as well as the capacity of a state is essential. Minimal states, for example, provide public goods like internal order, external defense, and basic public infrastructure, but little else. This limited role results in significantly weaker institutions than those found in maximal states. A maximal state, on the other hand, has much stronger institutions since it must also perform ‘functions such as adjudication, redistribution, and extensive infrastructural development.’ In addition, divided states are less cohesive and therefore have much less capacity than unified states. In short, ‘strong states are highly cohesive and tend to be maximal states; weak states are divided and tend to be minimal states’ (Desch 1996: 240–241).

According to Charles Tilly (1992) and Max Weber (1946) the capacity of a state is determined by 1) its ability to concentrate coercive force in a single organization or set of organizations, 2) its ability to clearly delineate its borders from other states, and 3) the presence of a legitimate governing authority. The stronger the institutions tasked with ensuring this ability, the stronger the state's ability to project its power. Others agree a state is just ‘a complex set of institutional arrangements for rule operating through the continuous and regulated activities of individuals acting as occupants of offices.’ The state has a specified territory ‘and monopolizes in law and as far as possible in all fact’ to protect its territory as it sees fit, in its own interest (Poggi 1978: 1). States lacking in capacity are unable to perform these tasks efficiently and effectively.

In sum, the literature views state capacity in terms of a state's 1) extractive, 2) coercive, and 3) administrative abilities. Extractive capacity refers to a state's ability to raise armies and extract capital from its population. Coercive capacity, on the other hand, refers to a state's ability to protect its borders from both internal and external threats. Finally, administrative capacity is defined as a state's ability to deliver public goods and services efficiently. This requires not only bureaucratic efficiency, but also control over the territory of the state. Important for each of these areas is a state's ability to control its borders from both internal and external threats. Thus, those states with the most capacity are the most successful at maintaining legitimate control over the monopoly of the use of force (Hanson and Sigman 2011; Tilly 1992; vom Hau et al. 2012; Weber 1946). The modern territorial state emerged as the most suitable way of organizing rule with the most capacity as a result (Tilly 1992). Conversely, states lacking the capacity typical of the modern territorial state do not maintain control over the entire population within its borders. In fact, the state may not even have clearly defined borders or may be governed partially or in whole by a foreign government. Additionally, capacity-poor states ‘lack the power to tax and regulate the economy’ and they do not have the ability to maintain a ‘monopoly over violence’ (Acemoglu 2005: 1199–1200). Jeffrey Herbst (2000), for example, argues African states lack the ability to extract resources from their citizenry, because they lack the necessary institutional capacity to do so.

Just as a state can gain capacity over time by strengthening its institutions, circumstances can also cause a state to lose its capacity as well. A substantial loss of population, for instance, can have dire consequences. Even Rome, for example, suffered from a series of devastating plagues which historians suggest contributed to its demise. Moreover, a state can overextend itself both in territory and military engagements. Empire-building in particular places considerable strain on a state. If the empire stretches itself too thin, if it comes under considerable pressure from attackers, if it fails to control or incorporate conquered peoples successfully, and in some cases even if it suffers significant loss because of disease, the state's institutions can weaken. Once its capacity is weakened it opens the door for outsiders as well as the conquered people who have not been homogenized to fight for independence. War, in general, can also seriously weaken the capacity of a state. Not only does it often result in a loss of territory, but if the war is damaging enough, the losing state's institutions are seriously weakened. This is especially so if the victor maintains at least partial control over the territory or government in the conquered state – a fate suffered not just by the Romans, but countless fledgling societies, newly formed states, and even Great Powers and other vast Empires throughout history.

In antiquity a state built institutions to increase its capacity to maintain society because it faced issues of competition-scarcity or threat of war, but after it acquired enough territory to satisfy its needs or it eliminated the threat, the need for strong institutions diminished. This is especially true in those areas where uninhabited territory was abundant because it provided a large buffer-zone for security. This protection made external clashes less likely. If peace lasted long enough, the state may lose even more of its capacity over time as the need for the institutions decrease. This is much less likely in the modern era, however, because states have expanded as far as possible without crossing into another state's territory. Thus, a buffer zone large enough to protect from an external threat no longer exists. In addition, because the world is much more interconnected and weaponry is much more advanced, threats are no longer just from a state's adjacent neighbor, but can come from any state anywhere in the world. As explained above, modern day states can still lose some, or all, of their capacity because of war or other circumstances, but the occurrence is less likely now than in antiquity.

Having established the parameters within which the variables are framed, I turn my attention to defining the variables used to test the hypothesis that war makes states.

Dependent Variable

State Strength: To operationalize the administrative capability of pre-modern states an ideal measure of state strength would capture the ability of a state to collect taxes. Unfortunately, because data is limited during this period, compiling that information for all states in all regions under investigation is not possible. However, the State Antiquity Index provides a comprehensive way of measuring state strength which is compatible with my definition. The index contains data on state strength for 149 countries from 1 to 1950 CE.5 To determine the level of state strength for each country during the selected time periods the index allocates points to a series of three questions asked about each state:

1. Is there a government above the tribal level? (1 point if yes, 0 points if no); 2. Is this government foreign or locally based? (1 point if locally based, 0.5 points if foreign [i.e., the country is a colony], 0.75 if in between [a local government with substantial foreign oversight]; 3. How much of the territory of the modern country was ruled by this government? (1 point if over 50 %, 0.75 points if between 25 % and 50 %, 0.5 points if between 10 % and 25 %, 0.3 points if less than 10 %) (Bockstette, Chanda and Putterman 2002).6

These questions accurately address the important components I use to define a state regarding whether there is a government and the ability of that government to control its borders.

To gather data for the index, Bockstette, Chanda and Putterman relied on the historical accounts for each country contained in the Encyclopedia Britannica and Macropedia articles in the Britannica online. The authors acknowledge the use of this particular source is ‘far from definitive,’ but due to gaps in the historical record for many states ‘no more specialized compilation… containing the necessary information exists’ (Chanda and Putterman 2007).7 The data divides the period into 50-year intervals and asks the above three questions during each segment. A score on a scale of 0–50 is then given based upon the responses to the questions. If a country receives a 0 then no government above the tribal level exists. A score of 50 indicates a strong state is in place which maintains complete control over its entire territory. Scores falling somewhere in the middle demonstrate some type of government was in place, but it either did not maintain complete control over the entire population, there was a foreign government in control, or a combination of local and foreign government control existed.

Because I am predicting the probability that conflict creates strong states, I create a variable which divides state strength into three categories. All states with a score ranging from 0–24 are coded ‘0’ for weak state. Moderate states, those ranging from 25–34, are coded ‘1.’ Finally, states with a score 35 or above are considered strong and coded ‘2.’

Independent Variable

Conflict: Although many conflict databases exist, finding comprehensive data that begins before 1800 is a difficult task. I rely on George C. Kohn's Dictionary of Wars (2000), a one-volume reference source on conflicts from ancient times to present. Though it does not account for all conflicts throughout history it does include a comprehensive list of all major and many minor conflicts that occurred across the globe from 3000 BCE to 1999 CE. In addition, Kohn relies on a broad classification of war defined as ‘an overt, armed conflict carried on between nations or states (international war) or between parties, factions, or people in the same state (civil war)’ (2000: 12). Moreover, Kohn defines international war as those events involving ‘territorial disputes, injustice against people of one country by those of another, problems of race and prejudice, commercial and economic competition and coercion, envy of military might, or sheer cupidity for conquest.’ Kohn includes any ‘organized effort to seize power’ such as a rebellion, insurrection, uprising, or revolt as a civil war. Finally, Kohn adds ‘conquests, invasions, sieges, massacres, raids, and key mutinies’ to the list of entries. Having such a broad definition of war is useful because it allows a diverse range of disputes in the data. This is particularly beneficial for earlier time periods since present day states had not formed and classification of many battles fall outside the scope of international wars biasing the results.

Conflict is an independent count variable measured as the total conflicts per country per year. Using a count variable yields more precise predictions than a binary variable since it can pinpoint precisely how much different levels of conflict impact state strength.

Control Variables

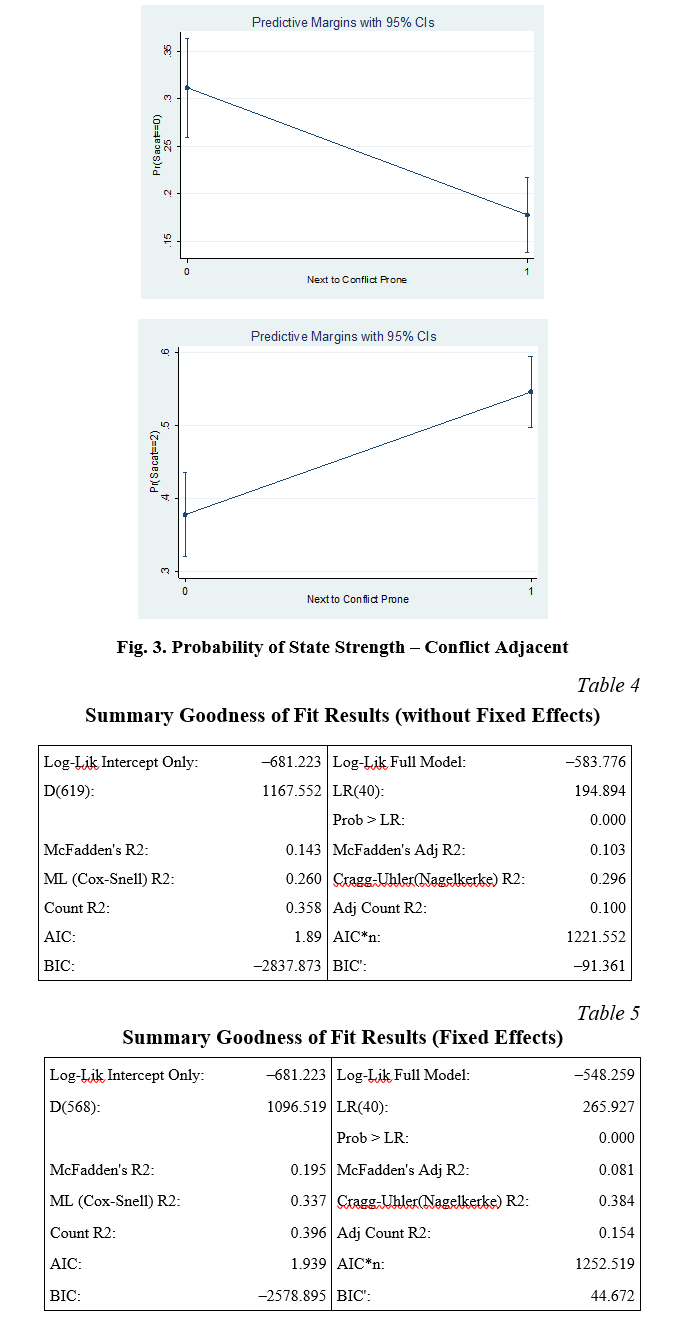

Conflict Adjacent: After remaining at a relatively steady rate with few exceptions for centuries, around 1000 – 1200 CE the number of conflicts dramatically increases. Because the external environment in which a state resides matters (Waltz 1979), it is possible states located next to a conflict prone state will also engage in conflict (offensive and/or defensive; see Mearsheimer 2001) regardless of its internal environment. To control for this effect, I include a dummy variable coded ‘1’ for any country next to one involved in a conflict and ‘0’ for those countries not adjacent to a conflict prone state. Although I do not include Middle Eastern countries in the dataset, I use the Dictionary of Wars to determine if any of those states were involved in a conflict and coded any adjacent country in the dataset appropriately.

Contiguous States: Prior research indicates states that share a border with one or more states are more likely to engage in conflict. Following the lead used by the Correlates of War project for coding the contiguous characteristic of states I counted the total number of known societies bordering the societies within the current territorial boundary of any given state from 0–1600. I relied on an exhaustive review of historical data including map archives and accounts of the various groups in each area, including all minor and major actors to determine how many bordering neighbors any one state or society had during this time. Some states, like Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, for instance, were not coded due to lack of available information.

Landlocked: I include a control variable coded ‘1’ for landlocked countries and ‘0’ for those that are not.

Island: I also include a control variable coded ‘1’ if the state is an island and ‘0’ if it is not.

Regional Controls: Qualitative case studies reveal state formation occurred at different times and at different rates. Asia developed much sooner, but a lot slower than Europe. Europe, on the other hand, arrived late on the state building scene, but progressed rapidly; Africa lagged behind both. To account for regional distinctions a dummy variable is included for Asia, Eastern Europe, Western Europe, and Africa.

Foreign Invasion: Foreign invasion is shown to weaken and strengthen a state, depending upon circumstances. Many states in the early phase of development were overcome with foreign threats of conquests; others residing in a peaceful environment. A dummy variable is included to account for the impact foreign invasion has on state development. All states that have mention of a foreign invasion in their historical record by a group other than Rome are coded ‘1’. No foreign presence in the state is coded ‘0’.

Roman Occupation: Qualitative case studies reveal the presence of Rome in a state significantly impacts its growth. The findings indicate while Rome may help elevate most states slightly in strength, in the long term, its presence weakens the states development. This results because despite Roman institutions established to maintain the military establishment, Rome did little to strengthen the institutions in the state it occupied in any other way. This lack of attention to institution building is evident after the fall of Rome. Europe, left with no rule of law and because Rome did little in the way of state building in these areas to help the inhabitants enforce it on their own, state strength was weakened. The Dark Ages are the result. Though states did recover from Rome's retreat, it is evident Rome set states back in their development at least temporarily. Every state in which Rome had a presence is therefore coded ‘1’. A lack of Roman presence is coded ‘0’.

Roman Withdrawal: Since the fall of Rome was so problematic for its foreign territories, the first year in which Rome's presence is no longer dominant is coded ‘1’. All other years are coded ‘0’.

Plague: Qualitative case studies also reveal states suffered significant setback in population levels and, in many cases, their strength because of several devastating plagues that occurred throughout history. Thus, any year in which the historical record indicates a state suffered a severe loss from a plague is coded ‘1’. Plague-free years are coded ‘0’.

Data Analysis

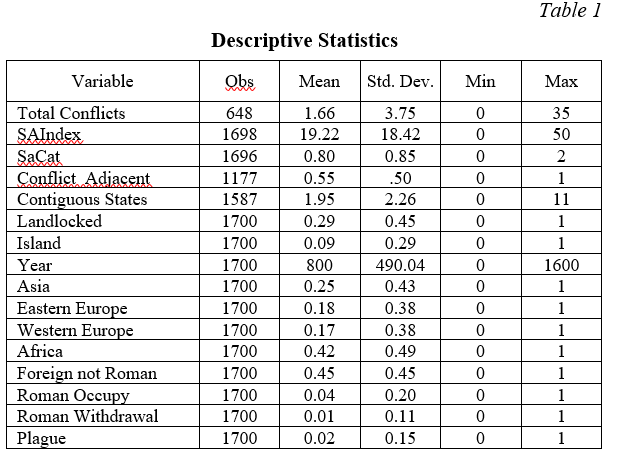

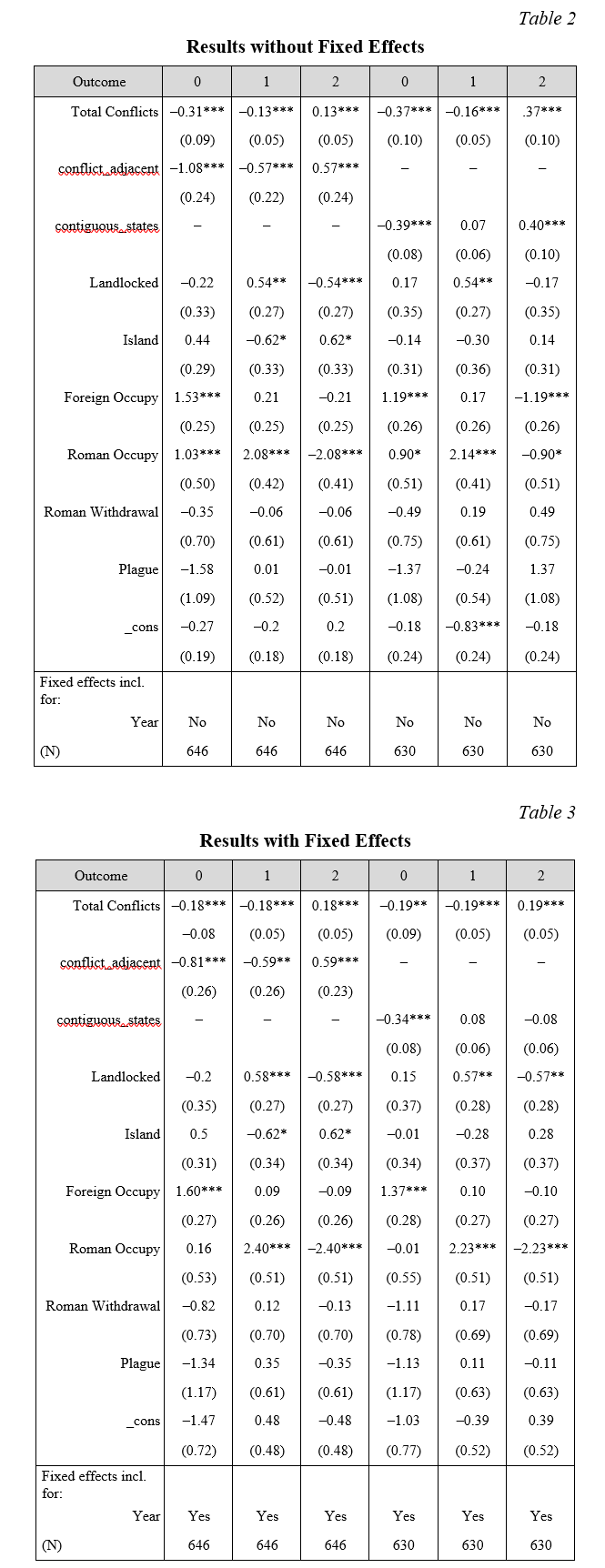

I test the hypothesis that war makes strong states by using panel data and multinomial logistic regression to predict whether conflict increases state strength. In this model I use a count variable of the total number of conflicts per year for each country. This is appropriate since the hypothesis suggests the higher the number of conflicts, the stronger the state. I also include conflict_adjacent in this model since, as previously discussed, sharing a border with a conflict prone neighbor yields a degree of uncertainty forcing a state to defend itself against potential aggression. A strong state would certainly be beneficial in this regard. Finally, I control for landlocked and island states, Roman as well as foreign occupation, Roman withdrawal, occurrence of the plague as well as fixed effects for year. I do not control for fixed effects for region in this model. Doing so produced extremely large error terms for each of the regional controls and the constant. Goodness of fit tests reveal model specification is improved significantly when not controlling for region. Fixed effects for year improve the model only slightly. Table 2 displays the results.

The total number of conflicts a state is involved in does increase the probability that it will develop a strong state structure. In addition, conflict adjacent states are also more likely to have strong structures. Landlocked states are more often moderate states but have less chance of becoming strong. Islands, on the other hand, have a slightly higher chance of developing a strong state, but it has no significance on whether a state is weak.

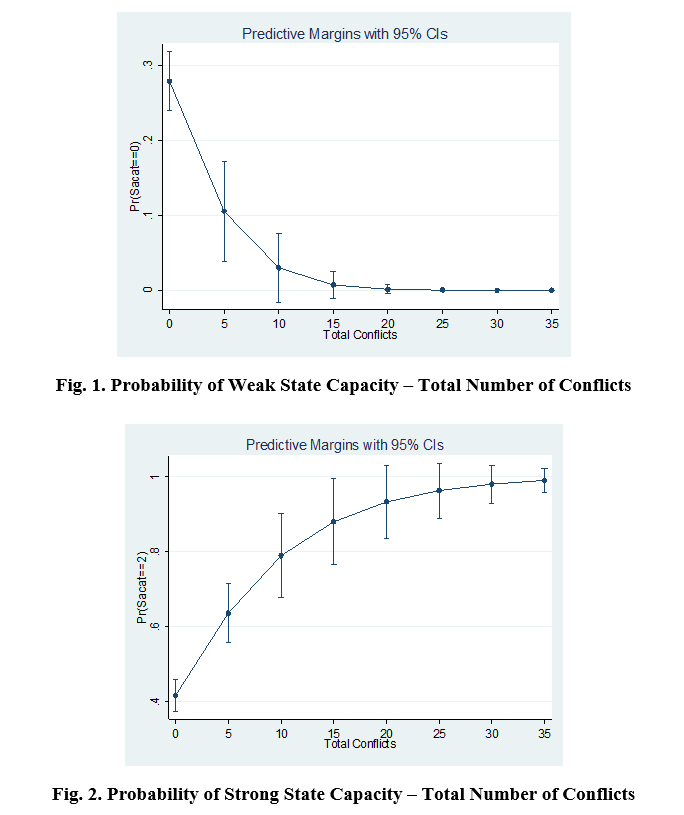

As Figure 1 shows, as total conflicts increase the probability that a state will develop weak institutional capacity decreases. Whereas, Figure 2 shows as total conflicts increase, the probability that a state will develop strong institutional capacity likewise increases. In fact, a state that engages in less than five conflicts has more than a seventeen percent (17 %) chance of remaining weak. More than five (5) conflicts in a period, however, yields less than a ten percent (10 %) chance a state has a weak structure. A state that engages in fifteen or more conflicts has less than a one percent (1 %) chance of being weak. Conversely, the more conflicts a state faces, the higher its probability of developing a strong state structure. States that engage in fifteen (15) or more disputes have an eighty-eight percent (88 %) chance of being strong. Twenty-five (25) or more conflicts increase the chance to ninety-five percent (95 %) or greater. Weak states are located next to peaceful states only eighteen percent (18 %) of the time. On the other hand, fifty-five percent (55 %) of states located next to conflict prone states are strong. Landlocked states have an eighteen percent (18 %) chance of remaining weak, whereas the likelihood it will develop into a strong state increases to forty-three percent (43 %). Islands, on the other hand, are only fifteen percent (15 %) more likely to become strong than remain weak.

Rome's presence produces varying results depending upon the classification of the state. Roman occupation improves a weak state's condition by four percent (4 %). In other words, if Rome occupied a state's territory, the state was strengthened, but only slightly. Rome's impact on strong states is significant, however. A state left unconquered by Rome has a thirty-two percent (32 %) chance that it will become strong. Rome's presence, however, means states only have an eighteen percent (18 %) chance of developing strong institutions. This finding is particularly intuitive because it confirms that Rome did not establish strong administrative structures in these areas. This confirms why the areas were so weak after Rome fell; Rome's presence hindered, not helped, developing states.

In sum, though location is important, and conflict prone neighbors can induce states to develop stronger structures, the findings confirm the hypothesis that states that engage in conflict more frequently are more likely strong.

CONCLUSION

The findings confirm Tilly's theory that war makes states. The findings also show how conflict between just two states in an area can have a reciprocal effect on other states in the region. Finally, the results yield interesting findings regarding the role Rome played in the state making process. Notably, Rome's presence hindered, not helped, developing states.

The results are important for adding to our understanding of how states developed, lending support for coercive theories that find a positive correlation between the engagement in conflict and the strengthening of state institutions. These findings do not account for economic or class-based theories' arguments regarding the role the market or cultural cleavages, etc. play in the formation of states. Nevertheless, it is clear conflict serves as an impetus for strengthening states, at least in the pre-modern era. The more efficient a state is at extracting taxes, drafting soldiers, providing resources, and maintaining control of its subjects the higher its chance of success in war. Without war the need for this type of strong structure does not exist and, thus, does not develop.

These findings are important, not only because it explains the difference in state strength in different regions, but it also provides insight into states in the modern era. If one of the main reasons why states develop strong state structures is related to the amount of conflict it faces, then that might explain why developing states in the modern era still find it difficult to create the type of strong states that flourished in Europe for centuries. War8 creates a powerful incentive to find the most efficient way to structure a state. Without this incentive, the motivation needed to force states on a rapid path of development does not exist.

NOTES

1 Though economic or class-based theories may also explain the formation of states, it is impossible to quantitatively address each of these competing debates in this paper. As a result, focus is solely on testing Tilly's theory.

2 The type of economic system a state develops determines its strength. The ability of institutions to achieve economic growth, the timing of development, and the type of structure in relation to the strength of the state drives the formation of the state. Others argue the ability of a state to foster trust and cooperation for the coordination of activities is important. States that create a more unified society and are better equipped at instilling trust gain legitimacy and therefore strength. Class-based theories of state formation, on the other hand, argue cleavages in society determine the structure of a state.

3 As states began to focus on non-military activities, however, ‘military expenditure declined’ relegating the ‘military organization…from a dominant segment of the state structure to a more subordinated position’ (Jönsson et al. 2000: 69).

4 I borrow Max Weber's definition of a bureaucracy (see Weber, M. 1946. In Max Weber: Essays in Sociology. H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills eds. Oxford: Routledge Paperback).

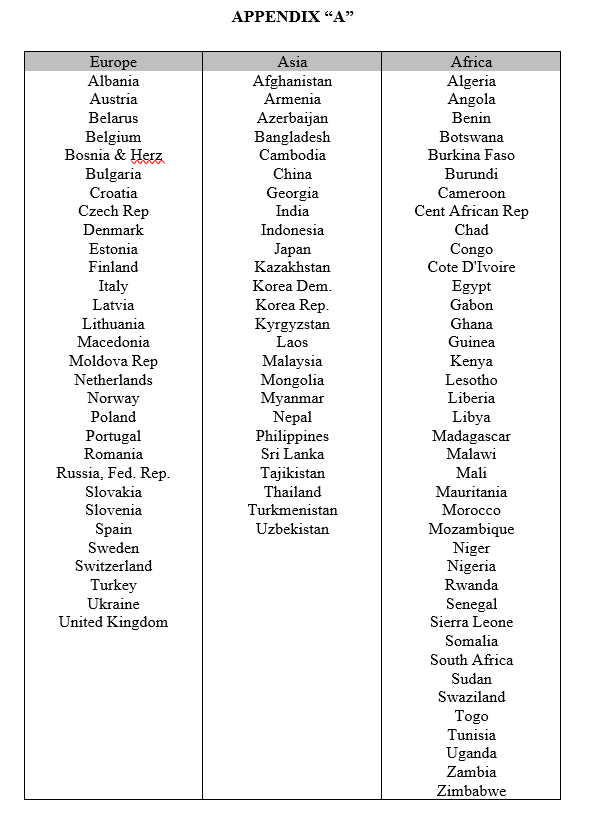

5 For a complete list of countries included in the dataset used for this project see Appendix A.

6 For a detailed description of how the scores are tallied see Valerie Bockstette, Areendam Chanda and Louis Putterman. 2002. ‘States and Markets: The Advantage of an Early Start.’ Journal of Economic Growth 7: 347–69.

7 Despite the limitations of the data sources, the index created by Bockstette, Chanda and Putterman has appeared in a wide range of peer reviewed publications and has been cited numerous times in a variety of studies.

8 I refer specifically to international and not civil war in this instance.

REFERENCES

Acemoglu, D. 2005. Politics and Economics in Weak and Strong States. Journal of Monetary Economics 52: 1199–1226.

Bueno de Mesquita, B. 2003. The Logic of Political Survival. The MIT Press.

Bockstette, V., Chanda, A., and Putterman, L. 2002. States and Markets: The Advantage of an Early Start. Journal of Economic Growth 7: 347–69.

Carneiro, R. L. 1970. A Theory of the Origin of the State. Science 169: 733–738.

Chanda, A., and Putterman, L. 2007. Early Starts, Reversals and Catch-up in the Process of Economic Development. Scandinavian Journal of Economics 109 (2): 387–413.

Connelly, M. 2003. A Diplomatic Revolution: Algeria’s Fight for Independence and the Origins of the Post-Cold War Era. Oxford University Press.

Connor, W. 1978. A Nation is a Nation, is a State, is an Ethnic Group is a… Ethnic and Racial Studies 1: 377–400.

Cooper, F. 2005. Colonialism in Question: Theory, Knowledge, History. University of California Press.

Desch, M. C. 1996. War and Strong States, Peace and Weak States? International Organization 50: 2.

Diamond, J. 1999. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Society. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Ertmann, Th. 1997. The Birth of the Leviathan: Building States and Regimes in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fukuyama, F. 2011. The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution. Farrar, Straus and Girous.

Glete, J. 2002. War and the State in Early Modern Europe. London: Routledge.

Hanson, J. K., and Sigman, R. 2011. Measuring State Capacity: Assessing and Testing the Options. Paper Prepared for the 2011 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association. Sept., 1–5.

Herbst, J. 2000. States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ikenberry, G. J., Lake, D. A., and Mastanduno, M. 1996. Approaches to Explaining American Foreign Economic Policy. Cornell Paperbacks.

Johnson, Ch. A. 1984. MITI and the Japanese Miracle. Stanford University Press.

Jönsson, Ch., Tägil, S., and Törnqvist, G. 2000. Organizing European Space. London: Sage.

Katzenstein, P. 1976. International Relations and Domestic Structures: Foreign Economic Policies of Advanced Industrial States. International Organization 30 (1) (Winter): 1–45.

Kennedy, P. 1987. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. New York: Random House.

Kohn, G. C. 2000. Dictionary of Wars. Checkmark Books.

Kumar, K. 2010. Nation-States as Empires, Empires as Nation-States: Two Principles One Practice? Springer Science+Business Media. (January).

MacMillan, I. C. 1978. Strategy Formulation: Political Concepts. St Paul, MN: West Publishing.

March, J. G., and Olsen, J. P. 1989. Rediscovering Institutions: The Organizational Basis of Politics. The Free Press.

Mearsheimer, J. 2001. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: W. W. Norton.

Migdal, J. S. 1988. Strong Societies and Weak States: State-Society Relations and State Capabilities in the Third World. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Mitchell, T. 1991. The Limits of the State: Beyond Statist Approaches and Their Critics. The American Political Science Review 85: 1.

Morganthau, H. 1948. Politics among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Poggi, Gianfranco. 1978. The Development of the Modern State: A Sociological Introduction. Stanford University Press.

Schweller, R. 1992. Domestic Structure and Preventive War: Are Democracies More Pacific? World Politics 44: 2.

Scott, J. C. 2009. The Art of Not Being Governed. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Spryut, H. 1997. War, Trade, and State Formation. In Boix, C., and Stokes, S. (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tilly, Ch. 1992. Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 900 – 1992. Oxford: Blackwell.

Vom Hau, M., Scott, J., and Hulme, D. 2012. Beyond the BRICs: Alternative Strategies of Influence in the Global Politics of Development. European Journal of Development Research 24: 2.

Waltz, K. 1979. Theory of International Politics. New York: McGraw Hill.

Wenke, R. J. 1999. Patterns in Pre-History. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press.