The Analysis of Iran's Foreign Policy from a Sociohistorical Perspective

Journal: Social Evolution & History. Volume 21, Number 2 / September 2022

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/seh/2022.02.04

In its contemporary history, Iran has experienced three different political systems, each of which, the Qajar, Pahlavi and the Islamic Republic, has had different foreign policies. There are many instances of Iran's foreign policy during this period such as acting as a buffer state, efforts made to employ a third force, a policy for nationalizing the oil industry, a strategic alliance with the United States, the neither East nor West policy, and attempts to change regional landscape, which may seem contradictory and sometimes irreconcilable. To give an account for this apparent contradiction, this paper seeks to revisit Iran's foreign policy during these three political systems in order to propose a general theoretical model which, we argue, the literature on Iran's foreign policy lacks. To do this, we go through three different sections: First, based on a historical sociological perspective, the necessary and adequate factors are considered to create an analytical and comprehensive model. Second, a theoretical model of Iran's foreign policy is proposed based on state-society relations. Finally, to demonstrate the analytical capability of this model and its link to Iran's foreign policy history, a brief account of Iran's foreign behaviors in contemporary history will be presented.

Keywords: historical sociology, Iran's foreign policy, social power, state/society relations, Qajar dynasty, Pahlavi dynasty, Islamic Republic.

Mohammad Mohammadian, Shahdi Beheshti University more

Amir M. Haji-Yousefi, Shahdi Beheshti University more

INTRODUCTION

Iran has experienced different political systems and subsequently different foreign policies in the last two centuries. This paper is an attempt to present a theoretical framework that has the capacity of analyzing Iran's foreign policy during the Qajar, Pahlavi and Islamic Republic eras. We argue that a state-society foreign policy perspective has a high analytical capacity to examine Iran's foreign policy due to its two prominent features: first, maximum effective variables in the framework make it capable of providing a comprehensive analysis. Second, placing the starting point of analysis within the social forces provides a good context to take temporal and spatial changes into consideration. Both features improve the potential of the framework to predict Iran's future foreign behaviors.

Majority of works that have been written on Iran's foreign policy can be classified in three categories: 1) Works which are mainly historical such as the History of Iran's Foreign Relations (Mahdavi 2005 [1384]), Iran's Foreign Relations from 1941 to 1978 (Azghandi 1997 [1376]), Russians in Iran: Diplomacy and Power in Qajar Era and beyond (Matthee and Andreeva 2018), All the Shah's Men (Kinzer 2008), History of Iran and Superpowers Relations (Zowghi 1989 [1368]) and many others. 2) Works which apply International Relations theories to Iran's foreign policy such as Iran's Foreign Policy in the Post-Soviet Era (Hunter 2010), Iran's Foreign Relations (Chubin and Zabih 1974), The Political Economy of Iran Under the Qajars (Amirahmadi 2012), Iran's Foreign Policy: From Khatami to Ahmadinejad (Ehteshami and Zweiri 2008), Iran's Foreign Policy in the Light of Regional Developments (Haji Yousefi 2005), and Foreign Policy of Iran in the Construction period (Ehteshami 1999 [1378]). 3) Works which try to formulate theories on Iran's foreign policy such as The Foreign Policy of Iran, 1500–1941 (Ramazani 1966), The Foreign Policy of the Islamic Republic of Iran: Theoretical Review and the Paradigm of Alliance (Sariolghalam 2000 [1379]), Topics on National Strategy (Larijani 1990 [1369]), Iran and the World: Continuity in one Revolutionary Decade (Hunter 1990), and Iran's Foreign Policy (Seifzadeh 2005 [1368]).

Notwithstanding some commonalities between the works of the third category and the main subject of this paper, it seems necessary to point to their differences. In her book, as its title suggests, Shireen Hunter argues that there are signs of continuity in Iran's foreign policy. Geographical features, historical experiences, nationalism, Islam and the external environment are among these signs which are the factors mentioned in our paper too. Despite Hunter's belief in the continuity and efficacy of these features in different eras of Iran's foreign policy, she merely analyzes the behavior of Iran in the 1980s and by no means intends to present a model or framework and analyze different eras of Iran's history.

In some arguments regarding the national strategy, Larijani has proposed a theory of Iran's foreign policy namely, theory of Ummulqora (Iran as the ‘Center of the Muslim World’) which emphasizes the characteristic of Islam as a dominant factor while other variables are ignored. In the same vein, despite the praiseworthy efforts made by Seifzadeh and Sariolghalam to establish a foreign policy strategy for Iran, their research is merely based on evidences and experiences of the Islamic Republic era and the history of Iran's foreign relations have no place in their analysis.

Ramazani believes that dominant theories in international relations have little analytical application to the foreign policies of small developing countries. For this reason, he suggests that analysts of the foreign policies of developing countries, including Iran, should pay special attention to the relations between legitimacy, permeability, distribution, identity, efficiency, etc., on the one hand and foreign policy, on the other. Based on Iran's contemporary history, he introduces the disproportion between the tools and objectives of foreign policy as the principal cause of Iran's failures in its foreign policy. Despite his exemplary achievements, Ramazani has not gone beyond proposing the importance of the relation between development and foreign policy. In fact, the kinds of behaviors in foreign policy that are caused by any crises such as identity and efficiency need to be questioned in a study. The answer to any of these questions may ultimately bring about a more valuable and richer analytical framework than Ramazani's preliminary proposal.

The outcome of this situation is the existence of a vast literature on Iran's foreign policy which resembles separated islands in different worlds with little communication and exchange among them. This may be a consequence of the dominance of the mainstream of International Relations in the views of Iranian experts who portray the state as a separate and integrated actor, separating domestic and international relations, and above all, with historical change and development having no place in their theoretical framework.

Finally, if the above evaluation of the literature of Iran's foreign policy is acceptable, the establishment of interconnections and reciprocal collaborations among different sections of this literature promotes the understanding and interpretation of Iran's foreign policy. This is the least of reasons why writing this paper is necessary. This necessity has been followed by relying on the approach of historical sociology as a link between theory and reality. This approach is related to history by making theory more explicit because description is the first step in the sociological explanation and also related to theory by challenging its historical presuppositions (Calhoun 1998: 855; Abrams 1982: 196). Accordingly, the main purpose of this paper is to suggest a theoretical framework for analyzing Iran's foreign policy in the country's contemporary history.

This paper consists of three interrelated sections: first, since our objective is to provide an analytical framework of Iran's foreign policy, the authors have attempted to identify the omnipresent forces, sources and factors effective in the formation of the state, as well as its decisions and reactions. Second, an analytical framework of foreign policy will be presented based on these power forces, sources and factors. Finally, we endeavor to apply the framework to the Qajar, Pahlavi and Islamic Republic eras very briefly.

1. SOURCES OF SOCIAL POWER AS A THEORETICAL BASIS FOR ANALYZING IRAN'S FOREIGN POLICY

In foreign policy every action might be influenced by a variety of both internal and international determinants. Obviously, to analyze the foreign policy of a country such as Iran, we should encounter a host of variables (Iran's civilization, role of clergies, academic scholars, elites, political and economic development, military, public opinion, minorities, ideology, tradition, modernity, geopolitics, market, international powers, regional and international systems, and many other factors). However, including them all within the framework of analysis will bring the risk of incoherence and a lack of internal consistency. This is probably the reason why experts in the field of Iran's foreign policy prefer to narrow their work to specific topics or time periods. Despite all mentioned, the claim of this paper is to propose a comprehensive analytical framework with maximum variables while still maintaining internal consistency.

In regards to categorizing and prioritizing the variables that affect foreign policy, it is reasonable to ask about the nature of these variables. What mechanisms make them effective? And through which channels and paths do they shape Iran's foreign policy decisions? The answer to the third question is one word: State. It is clear that all actors and forces must affect the state in order to meet their own goals and demands. That is, they try to convince the state, in a formal or informal as well as legal or illegal manner, to make decisions that meet their goals and demands. The efforts to gain power and form a state, introducing candidates for key positions, controlling the market and economic forces, shaping and influencing public opinion, imposing sanctions or threatening a state, are just some of methods adopted by domestic and international forces to affect the states' behavior. Therefore, we may say that the emergence of any kind of institution and mechanism at the structural level, which is referred herein as the forms of state, is the result of interaction among social forces at the agent level. That is, each different articulation of forces at the agent level leads to the emergence of a new form of state at the level of the governing structure of society, which brings about different institutions, mechanisms, procedures and decisions. Hence, for a better understanding of the orientation of foreign policy, we need to identify forces and mechanisms that shape political system in Iran.

A satisfactory answer to the first two questions improves the capability and superiority of the analytical framework from three perspectives: first and foremost, it shows that, contrary to mainstream theories, states are not monolithic and unified units. Secondly, by identifying the forces in the formation of the state, it is possible to identify different manifestations of social forces in Iran. Given the fact that in every manifestation there is a possibility that the position of forces within the main pillars of the state may change, the mechanism of influence of any of the forces may help to predict the type of foreign orientation of any state. Finally, it is the issue of change in foreign policy. Reliance on social forces as a starting point for analysis brings about the ability for the framework to predict a change in Iran's foreign policy in the verge of any change and development of social forces and their demands and interests.

To answer the first two questions, we may utilize Michael Mann's theory of social forces. In his works The Sources of Social Power (Mann 1986, 1993, 2012, 2013) Mann sought to root out the forces that shape various political systems, including city-states, empires, modern states, etc. It is necessary to point out that his theory is based on a significant and fundamental proposition that ‘societies are comprised of overlapping and intersecting networks of social resources of power.’ From his perspective, contrary to theories of Marxism, structuralism and functionalism, societies are not unified, consistent and separate totalities distinct from their neighboring regions and dividing nation-state building factors into domestic/foreign or internal/external is not easy (Mann 1986: 1–2).

Following the above proposition, Michael Mann asks if societies are comprised of social sources of power and tries to identify these sources. He recognizes four sources namely, Ideological, Economic, Military, and Political (IEMP) and examines their role in the making of political systems and the transformation of these sources through history. It should be noted that although it is theoretically possible to analyze these sources separately, in reality, they form societies, structures and institutions governing human life in the form of overlapping networks of social action. However, at times and in some societies, one of the sources may dominate social relations, but none of these sources alone form societies in the long run, and consequently he advises that states should include majority of social forces into their structure in order to become more stable and institutionalized (Mann 1986: 2–6; 1993: 59). Here we will discuss the mechanisms of action and the impact of these power sources.

Ideological Power

This type of power originates from three sociological traditions: First, acknowledging that direct sensory experience as the only way to recognizing the world is imperfect. Second, that common norms and perceptions are necessary for continued social collaboration. Third, the ritual/aesthetic practices, which cannot be reduced to rational sciences. As one cannot resort to logic and reason when confronting a song, a distinctive type of power is transmitted through melodies, dances, religious rituals, visual arts, etc. To Michael Mann, this kind of power may include a variety of modern and traditional ideologies such as liberalism, socialism, Islam or Christianity, and so on. More importantly, according to Mann, ideology is a kind of ‘diffused power’ that, contrary to the military power, mobilizes and activates individuals impulsively and voluntarily, and therefore it is not limited to borders and geography (Mann 1986: 23; 1993: 7). According to him, this diffusion has two principal forms: transcendence and imminence. An ideology is transcendent since it ‘may diffuse right through the boundaries of economic, military, and political power of organizations.’ It is immanent since it ‘may solidify an existing power organization, developing its “immanent morale’ (Mann 1993: 7). This in turn leads to ‘the revolutionary or liberating qualities of ideology, the sense of freeing oneself from local power structures, more mundanely of freedom of thought’ (Mann 2012: 8).

Economic Power

This type of securing of material needs originates from the social organization of the extraction, transformation, distribution and consumption of the material resources. Considering the performance of production, the distribution and exchange relations at various local, regional and international levels, the economic power organization is a combination of intensive and extensive, diffused and authoritative power. Mass strikes are examples of a diffused and intensive power holding a spontaneous and voluntary state, while market-based transactions are of a diffused type of power acting extensively and unorganized. Overall, economic power is not controllable by a specific center and ‘penetrates most routinely into most people's lives’ (Mann 1986: 24; 2013: 2).

Military Power

Exigency to defend and invade is the root of the formation and the essence of this type of power. Military states of the modern era are concentrated forms of this kind of power, which rule their subordinates intensively and compulsorily and enforce strict control and surveillance over their borders. The impact of such power on society can be either positive or negative. On the one hand, it provides a center of power for compulsory cooperation and establishment of order, but on the other hand, creates the possibility for the emergence of eccentric military or terrorist forces against central power. However, a system largely shaped by this type of power will be based on the concentration of sources, and more importantly, on that the military forces of every society must be consistent and compatible with the needs, geopolitical conditions and their legitimate use (Mann 1993: 8, 259).

Political Power

Political power stems from the benefits of the centralization, institutionalization and delimitation of many human social relations that are divided into internal and external dimensions or geopolitics. Michael Mann restricts this type of power to a centralized control and administration of affairs by the state within the framework of geographical borders, and those who control the state, are capable of acquiring distributive and collective powers (Mann 1986: 26). To some, dividing political power to geopolitical and internal dimensions has enabled Mann's theory to incorporate geopolitical topics into historical sociology and to show the roleplaying and effect of military forces, conflicts and diplomatic relations on international relations and their interplay on state formation (Collins 2005: 21).

Overall, the propositions of Michael Mann's theory bring to mind a type of state different from that proposed by the dominant theories of International Relations; a state whose societies are comprised of intersecting networks of four power sources; all of these sources are more or less involved in the formation of a political system; no state can survive by merely relying on one of the sources; and foreign and international forces have an impact on the formation of the state. All these propositions create a state, whose main characteristic is change and dynamism. A state that has emerged from society's social forces and its surrounding environment (domestic and international), has shaped social forces and may be changed by the same social forces as societies will not be institutionalized to the extent that there would be no way for the formation and emergence of new power relations.

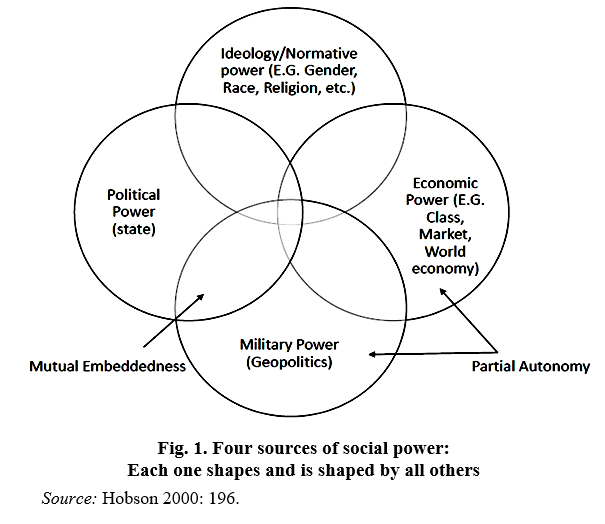

Michael Mann has clarified the sources of social power and the mechanism of their functions in the formation of societies. Since he assumes the societies as multiple overlapping and intersecting socio-spatial networks of power, he insists that each has its own partial autonomy and, though influencing and mutually structuring each other, cannot be sociologically reduced to one single factor (Figure 1). According to Hobson, ‘this assumes that there are no clear boundaries between the different power sources and actors. While often all four power sources might equally affect social development, it is possible that at specific moments one or two power sources might be singled out as primary, though for a short period’ (Hobson 2000: 194).

In fact, what explains the actions and behaviors of a state is the different status of each of the four power sources in the articulation of the existing system or in a sense, the state-society relation. That is, with the change in relations between dominant and marginal forces in the formation of the structure of the political system, the behavior and functioning of the state, including that in foreign policy, will undergo change. In the next section, with reference to characteristics and specifications of the economic, ideological, military and political forces of Iran's society, we attempt to propose two rules of Iran's contemporary history and foreign behaviors as well.

2. SOURCES OF SOCIAL POWER AND TWO RULES OF IRAN'S CONTEMPORARY HISTORY

The starting point of our argument was that any foreign policy adopted by a state originates from domestic social forces. In the second phase, the nature of these forces and the question based on what mechanisms they act on, was addressed. The answer to this question was the four sources of ideological, political, economic and military power, each of which had its own mechanism of influence. The answer to this question was important because the contribution to and position of each of these sources in the structure of the political system overshadows the behavior and orientation of the state's foreign policy.

Accordingly, it is now necessary to ask: what kinds of state-society orders have been brought about by the sources of social power in Iran's contemporary history? For example, have the economic forces played a dominant role? What role did the military or ideological forces play in the changes and developments of the state? What forces have been marginalized?

Studying Iran's contemporary history from the perspective of Mann's theory, we may propose two analytical rules to explain foreign policy of Iran. First, it shows that the four sources of economic, political, military and ideological power, with their inner characteristics and changes, have brought about various forms of state in Iran's past two hundred years. In other words, different forms of state in Iran are the consequence of different articulation among social forces (the economy includes bazaris [marketers]), merchants and traders in the Qajar era; traditional and modern economic forces in the Pahlavi and Islamic Republic eras; military forces including tribes in the Qajar era, who supplied the government's military, the military during the Reza Pahlavi and Mohammad Reza Pahlavi eras, as well as the IRGC and the army during the Islamic Republic era; ideological forces including modernists, nationalists, Islamists, etc.; political forces of the Shah or the political leader, political elites, governmental authorities, bureaucrats, members of Parliament, as well as geopolitics including economic-political regional-international systems; also change in relations among these sources of power in the order ruling over the society (Bashiriyeh 2001 [1380]: 27–28, 55, 70, 89, 91; Rajaee 2013 [1392]: 30, 80, 14; Gnoli 2016 [1395]: 47; Martin 2005: 4, 17–18; Ajoudani 2003 [1382]: 160, 172; Foran 2001 [1380]: 74; Lambton 1960 [1339]: 268, 280; and Gasiorowski 1991 [1371]: 94, 97).

Theoretically, each of the four sources have the same degree of importance; however, it is their position in the realm of reality and in the ruling order compared to other sources which determines the degree of their significance in the final analysis. In fact, one particular source may be the most influential factor in one era while in another era it might have a marginal role. For example, each of the sources may be among the main and most influential pillars in a political system during a specific period (such as the clergy during the Qajar and the Islamic Republic eras, military forces in the Reza Pahlavi era and after the Coup of August 19, 1953), while in another era they may have a marginal, dissenting and protesting role toward the existing order (such as the clergies and intellectuals after the Coup of August 19, 1953; and the military in the 1940s). In the final stage, Iran's foreign policy is the outcome of different forms of state, which in turn have emerged from the interplay of various competing social forces.

Second, according to Figure 1, Iran's contemporary history admits that none of the political systems in Iran have been able to keep balance among the four sources of social power. Reliance on one or two sources of power and marginalizing the remaining forces results in specific kinds of domestic and foreign behaviors. Evidently, social forces make political structures to meet their preferences but if the ruling structures resist satisfying societal demands and remove or marginalize social forces, these forces will attempt to change the ruling structures sooner or later. Some examples of this process in practice could be revolutionary changes in Iran's foreign policy after the Constitutional Revolution, Reza Shah's abdication, the Islamic Revolution of 1979, and after the presidential election which brought president Khatami to power in 1997.

According to Mann's theory (Figure 1) and based on the two rules of contemporary history of Iran derived from it, analyzing Iran's foreign policy in each era requires a three-stage process: at the first stage, the status and position of each of the power sources in the social relations of Iranian society should be studied. For example, whether the economic forces are of greatest importance or the military or any other sources. At the second stage, the focus of research should be shifted from the level of societal forces onto the state structure, and the type of political system structure, which is the result of the relations among the forces at the level of society, should be examined. In fact, it should be investigated how many social forces are included into state structures. For example, if within a political system, the military has a special place, an authoritarian structure may form. At the final stage, it is necessary to analyze Iran's foreign behaviors and orientations. By identifying the type of order which rules society or the state-society relations, the direction the state will take, will more or less become clear. In the next section, we try to use this framework to look very briefly at the foreign policy of various states in Iran's contemporary history.

3. ANALYSIS OF IRAN'S FOREIGN POLICY DURING THE QAJAR, PAHLAVI AND ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ERAS

In the first part of this paper, it was argued that individuals and social forces of each society, based on the available sources of power, form the structures and institutions of their society, including the state. In the second part and based on the sources of social power and the specifications of these sources in Iranian society, a framework of state-society relations was proposed for Iran's foreign policy analysis. Here we try to mention some examples of Iran's foreign policy in three different periods of Iran's contemporary history through the spectacles of the above model.

In the study of the sources of social power, it was mentioned that states should try to use the maximum of the four power sources for their survival and stability. Iran's contemporary history acknowledges that most of the time the Iranian states have been based largely on one of the power sources and other sources were marginalized, thus failing to create institutions with the capacity to attract the majority of social forces. For the same reason, the marginalized forces have, after some time, been able to form their relations and networks of power and wait for an opportunity to challenge or overthrow the ruling order.

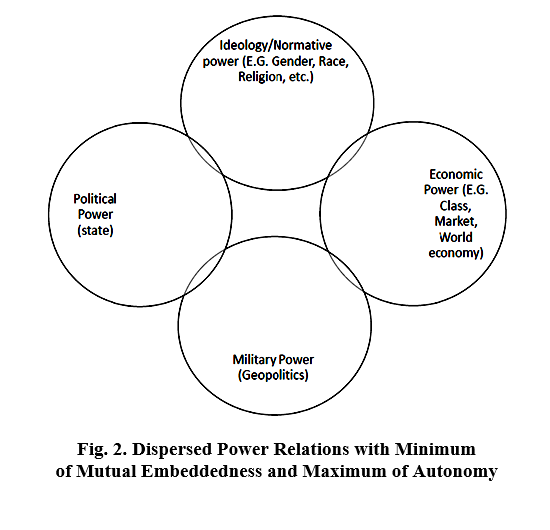

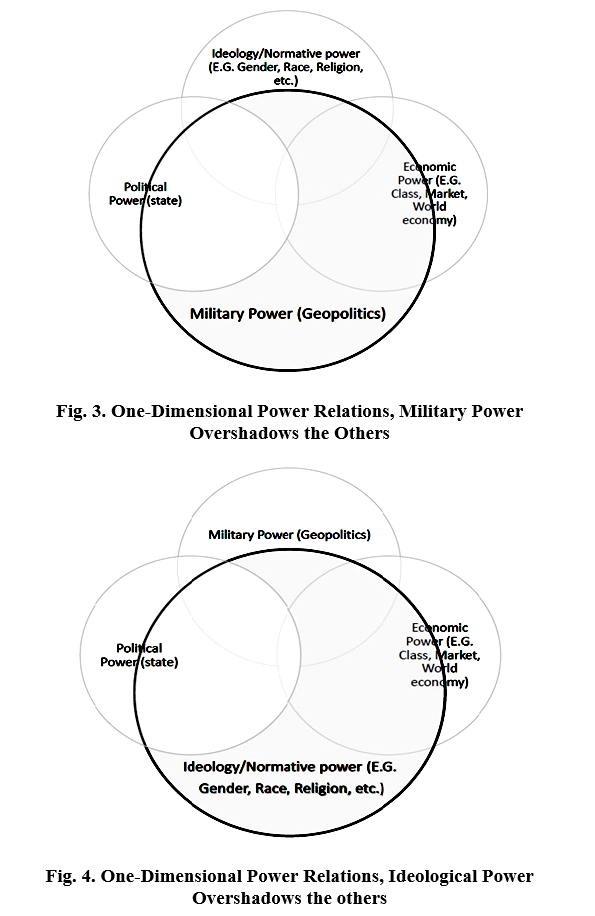

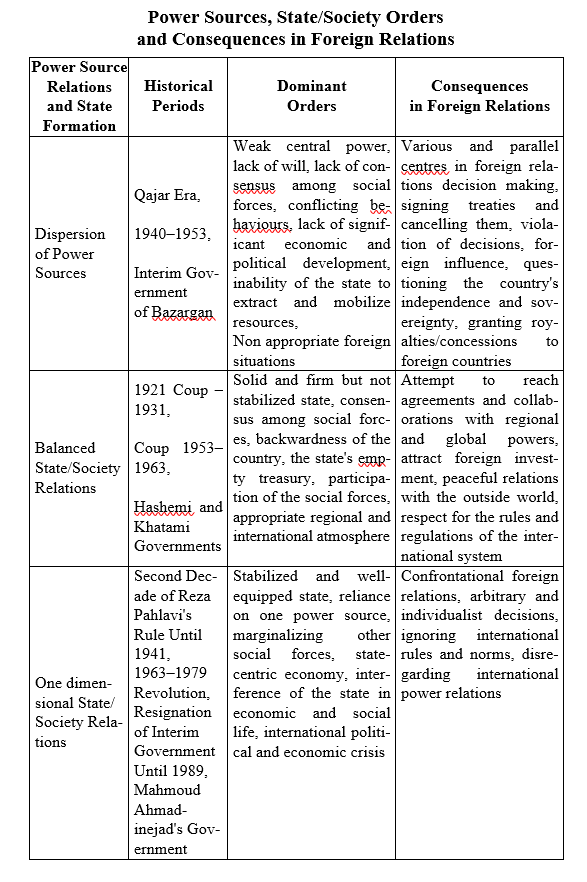

Applying the power sources relations and the two rules, we could recognize three kinds of interrelated state/society orders in Iran's contemporary history, each with its specific foreign behaviors (Table 1). First relates to the periods where power sources are dispersed (Figure 2). The Qajar era (Dowlatabadi 2006 [1387]: 63; Hedayat 1965 [1344]: 64, 167; Lambton 1980 [1359]: 85; Foran 2001 [1380]: 169; Adamiyat 2006 [1385]: 369), during the 1940s (Azimi 1993 [1372]: 27; Maleki 1989 [1368]: 309; Lenczowski 1977 [1356]: 215; Bullard 1992 [1371]: 623), and the period of Mehdi Bazargan's interim government (Bazargan 1984 [1363]) are placed in this category. Second order which is followed by the first one, regards periods where balance is the dominant principle over state/society relations (Figure 1). The periods from the 1921 Coup to 1931, from the 1953 Coup to 1963, and the Hashemi and Khatami governments, are placed in this category. It should be noted that although during these periods the central authority believed in the participation and collaboration of the majority of social forces, the establishment and nature of the political system was rooted in one of the sources of power and ultimately the overreliance on that one source and the marginalization of the other sources of power, resulted in the emergence of the third period. Unlike the second period, the exercise of power in the third period has been dependent on one source of power and is therefore authoritarian, and individualistic in its decision-making. The second decade of Reza Pahlavi's rule until 1941, the periods from 1963 until the 1979 Revolution (Figure 3), as well as from resignation of Bazargan interim government until 1989 and finally Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's government, fall under this category (Figure 4). We believe that as the result of the variety of power relations, the state's behaviors have also been different in the domestic and international arenas, which is summarized in Table 1.

In the first order of state/society relations, as the result of the dispersion of power sources, we witness a weak and fragile central power, with a lack of will, conflicting behaviors, unsubstantial decisions, lack of significant economic change and development, inability of the state to extract and mobilize resources, the mounting presence and interference of foreign powers in internal affairs, questioning the country's independence and sovereignty and so forth. From a geopolitical view, these periods have been associated with intense rivalry and antagonism among superpowers over their influence and impact on Iran's behaviors. The implications include the presence and influence of foreign powers in Iran, particularly Russia and Britain during the Qajar era, the intense competition between the former Soviet Union and Western countries during the 1940s, especially over the withdrawal of the Soviet troops from Iran, as well as internal chaos and the interference of foreign forces during the interim government of Mehdi Bazargan.

In the Qajar era, due to inability of the central power to extract resources or to tax, it was forced to grant royalties to foreign powers. In many cases, granting royalties was faced with the opposition of various domestic forces, including the bazaar and the clergy, and with the abolition of these royalties, many penalties were imposed on Iran. Many examples can be mentioned. For example, during Mozaffaredin Shah's era, Ottoman troops had occupied the border regions of Iran following the border disputes between Iran and the Ottoman Empire. On the other hand, many Armenians, due to the Ottoman government's ill-treatment of them, had sought refuge in Iran and were supported by the Iranian government. The Ottoman Embassy in Tehran, referring to the great verses of the Ayatollahs Mirza Abutaleb Zanjani, Agha Seyed Hassan Shoushtari and Seyed Abdollah Behbahani, received a fatwa that the Iranian government's actions in support of Christian Armenians were not permissible (Ajoudani 2003 [1382]: 105, 106). The event of cancelling the tobacco royalty is also well known in Iranian history. These are only two of the cases that show the effects of dispersed power sources in foreign relations, which led to the opposition of forces, failure to implement decisions and the stagnation of society.

In the 1940s, the turmoil and conflict among social forces, disturbed the political system and foreign relations to a degree that Churchill claimed that ‘Iranians themselves tranquilize each other’ (Saikal 2005 [1384]: 125). Apart from Churchill's claim, historically speaking, one of the main factors behind the failure of the nationalization of the Iranian oil industry and the collapse of Mosaddegh's government was not only the power of the USA and British-led domestic opposing forces, but the conflict and disunity within Mosaddegh's government and the National Front (Azimi 2017 [1396]: 38). Similarly, during the interim government of Mehdi Bazargan, the dispersion of power was reflected in Iran's domestic and foreign behaviors. For example, while the interim government was negotiating with the US ambassador and trying to normalize relations abroad, the US Embassy inside of Iran was being attacked.

The second era emanates from the previous one. It means that the lack of stability, the severe backwardness of the country, the state's empty treasury, international threats, and so on, led to a new state/society relation. In this order the central power needed the participation and collaboration of the social forces, and domestic and foreign investments to stabilize its power. Therefore, some degree of balance existed among the power sources inside the political system. Interestingly, from a geopolitical perspective, these periods have usually been accompanied by the decline of the superpowers' interference in Iran or the cooperation and détente among them with respect to Iran. For instance, the agreement and consent of the Soviet Union and Britain over territorial integrity of Iran and establishing a centralized state during Reza Shah's era, the support of the West and particularly the United States of Mohammad Reza Shah after the coup of August 1953, and the appropriate regional and international atmosphere after the collapse of the Soviet Union for the accommodationist policy of Hashemi and Khatami governments, are worthy of mentioning.

Therefore, the second era is shaped by both contribution of majority of social forces into state structure and appropriate international conditions. The result of such order in the foreign arena is an attempt to reach agreements and collaborations with regional and global powers, attract foreign investment, peaceful relations with the outside world, respect for the rules and regulations of the international system and so on. While for example, during the period after the interim government of Mehdi Bazargan, the revolutionary forces made attempt to export the revolution, violate the international military rules, and not acknowledge international organizations, immediately after the Iran-Iraq war and during Hashemi Rafsanjani's era, we witness an accommodationist foreign policy seeking to normalize its relations with the regional Arab countries, attract capital from European countries and, in general, present itself as a member of the international society.

In the third era, we are faced with a stabilized, wealthy and well-equipped state. The majority of the social forces are marginalized and the state's behaviors are authoritarian, interventionist and individualistic. This kind of state intervenes exceedingly in economic and social life, which was accompanied by rapid social change and economic growth. This order was brought about by the weakness of domestic social forces which were marginalized by the state as well as some political and economic developments in the international system. For example, the Great Depression of 1929 and the strong state presence in the economy, the rise in oil prices during the 1970s and the first decade of the 21st century, which introduced unearned revenue into the state treasury and resulted in nothing more than the arbitrary intervention in the economy, and finally the events of September 11 and ensuing developments in the immediate environment of Iran, led to the expansion of the state's involvement in society.

The repercussions of this situation in foreign relations were arbitrary and individualistic decision making which led to ignoring international rules and norms and disregarding international power relations. For example, we can mention the tearing of the Iran-Britain oil contract and the increasing presence of Germany in Iran during Reza Shah, which ultimately led to the occupation of Iran. Furthermore, Mohammad Reza Shah's desires for military intervention in regional states, financial donations to regional states, disregard for the social sensitivities in establishing relations with Israel, and overreliance on the US support worth mentioning which led to the 1979 Revolution.

Also, during the Islamic Republic era and following the resignation of the interim government until 1989, we can refer to some prevalent revolutionary ideas as well as actions such as discourses advocating exporting the Islamic Revolution to the countries of the region; the takeover of the US Embassy in Tehran; and disregarding the international rules, norms and institutions, which facilitated Iraq's invasion of Iran in 1980 and the outbreak of an eight-year war as well as sanctions and isolation of Iran form the international community. Similarly, during Ahmadinejad's presidency, questioning the international order, unilateral action in the field of nuclear energy expansion, calling the UN Security Council's resolutions worthless, and the repeated threats of the destruction of Israel, resulted in nothing other than the intensification of numerous sanctions against Iran, the threat of military attack, international isolation, and the expansion of Iranophobia and so forth.

CONCLUSION

This article sought to explore continuity and changes in Iran's foreign policy in the past two centuries by studying three different yet interconnected sociohistorical phases. First, the foundations of Iran's foreign policy analysis, namely, the social forces and sources affecting the structure of the political system and its foreign behavior, were identified. At the second stage, by employing the power sources, two rules of Iran's contemporary history were proposed for analyzing Iran's foreign policy in different periods. Finally, at the third stage we tried to briefly apply the model to the history of Iran's foreign relations during the Qajar, the first and second Pahlavi, and the Islamic Republic eras and put them to test.

The application of the proposed model for the analysis of the foreign policy of each period has undergone a three-stage process; the first stage is the relations of the social power sources, the second is the structure of the political system and the third stage reflects the state-society orders in foreign relations. In the early stages of each period ‘the relations dominating the social forces of that period were identified’ in which ‘the structure of the political system emerged from these social relations.’ From all the interaction relations between the state structure and social forces, ‘three types of state-society orders’ were identified in contemporary Iranian history: 1. The dispersal of power during the Qajar period, the 1940s and the interim government of Mehdi Bazargan; 2. The balance of relations between state-society in the first decade of the Reza Shah era, the 1950s, and the governments of Hashemi Rafsanjani and Mohammad Khatami; 3. The concentration of power in the second decade of the Reza Shah era and after 1963 to the 1979 Revolution, after the interim government of Bazargan until 1989, and the presidency period of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Identifying

the governing orders of each era, was in fact, the provision of an analytical

framework for Iran's foreign behavior. Thus,

it was expected that the foreign behaviors of each period would be in

accordance with the prevailing order of society in that period; that is, every

state-society order would have different types of foreign behavior. According

to Iran's contemporary history, the dispersal of power has led to contradictory

behaviors such as signing treaties and cancelling them, policy discontinuity,

violation of decisions, recruitment of foreign forces and their dismissal,

foreign influence, threats, ultimatums and war, country occupation by foreign

forces and so forth.

Also, in occasions when state-society relations were balanced and social forces had a space for participation and presence in the political structure, peaceful and cooperative behaviors have prevailed in order to preserve and stabilize the status quo over Iran's foreign relations. Among these behaviors were the Soviet Union's satisfaction with the 1921 Treaty, amicable relations with the Britain and the United States and neighboring countries in the first decade of Reza Pahlavi's era, as well as the establishment of diplomatic relations with the Britain and closing the post-coup consortium agreement, the signing of the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), endeavoring to sign the Friendship Treaty with the Soviet Union in the 1950s, and the conciliatory accommodative foreign policy during the Hashemi and Khatami eras. To quote from James Rosenau, Iran's foreign approach may be categorized as ‘acquiescent adaptation’ in these periods (Rosenau 1970: 5).

Finally, at times when the power was centralized and the political system has stabilized its place and has marginalized all social forces, the ‘intransigent adaptation’ approach became dominant over Iran's foreign behaviors (Rosenau 1970: 5). In such occasions, there was no sign of participation and collective decision-making and foreign relations have become the exclusive domain of the individual or of particular individuals. In three periods during the Pahlavi regime and the Islamic Republic, we can see an increase in the presence of military security forces in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs which resulted in behaviors such as disregard for the rules and principles governing the relations between the great powers, questioning of democratic systems, intervention and prodigality abroad, attempts to export a revolution, disregard for the absolute rules of the international system, and the calling of the UN Security Council's resolutions worthless.

REFERENCES

Abrams, Ph. 1982. Historical Sociology. Cornell University Press.

Adamiyat, F. 2006 [1385]. Andisheye Taraghi va Hokoomate Ghanoone Asre Sepahsalar [Progressing Thought and Rule of Law in the Sepahsalar Era]. Tehran: Kharazmi.

Ajoudani, M. 2003 [1382]. Mashroute-ye Irani [Iranian Constitutional Movement]. Tehran: Akhtaran.

Amirahmadi, H. 2012. The Political Economy of Iran under the Qajars: Society, Politics, Economics and Foreign Relations 1796–1926. I.B. Tauris.

Azghandi, A. 1997 [1376]. Ravabete Kharejie Iran 1320–1357 [Foreign Relations of Iran 1941–1979]. Tehran: Ghoomes.

Azimi, F. 1993 [1372]. Bohran-e Democracy Dar Iran [Iran: The Crisis of Democracy]. Translated by A. H. Mahdavi. Tehran: Alborz.

Azimi, F. 2017 [1396]. Porse-ye Dar Negar Khaneh-ye Tarikh: Asnad Tazeh America Darbareh Kodetaye 1332 [An Inquiry in the Gallery of History: American New Documents about the Coup 1953]. Tehran: Journal of Negahe Nou 114: 11–56.

Bashiriyeh, H. 2001 [1380]. Mavane-e Tose'e-ye Siasi Dar Iran [Impediments to Political Development in Iran]. Tehran: Gaame Nou.

Bazargan, M. 1984 [1363]. Enghelabe Iran Dar Do Harkat [Iran's Revolution in Two ways]. Tehran.

Bullard, R. W. 1992 [1371]. Namehaye Khososi va Gozareshhaye Mahramaneh Sir Reader Bullard Dar Iran [Letters from Tehran: A British Ambassador in Second World War, Persia]. Translated by G. H. Mirza Saleh. Tehran: Tarhe Nou.

Calhoun, C. 1998. Explanation in Historical Sociology: Narrative, General Theory, and Historically Specific Theory. American Journal of Sociology 104 (3): 846–874.

Chubin, Sh., and Zabih, S. 1974. The Foreign Relations of Iran: A Developing State in a Zone of Great-Power Conflict. University of California Press.

Collins, R. 2005. Mann's Transformation of the Classic Sociological Traditions. In Hall J. A., and Schroeder R. (eds.), An Anatomy of Power the Social Theory of Michael Mann (pp. 19–32). Cambridge University Press.

Dowlatabadi, Y. 2006 [1387]. Hayat-e Yahya [Life of Yahya]. Vol. 1. Tehran: Ferdows.

Ehteshami, A., and Zweiri, M. (eds.). 2008. Iran's Foreign Policy: From Khatami to Ahmadinejad. Ithaca Press.

Ehteshami, A. 1999 [1378]. Syasate Kharejie Iran Dar Dorane Sazandegi [Foreign Policy of Iran in the Construction period]. Translated by E. Mottaghi and Z. Poustinchi. Tehran: Islamic Revolution Documents Center.

Foran, J. 2001 [1380]. Moghavemate Shekanandeh: Tarikhe Tahavolate Ejtemaie Iran az 1500-Revolution [Fragile Resistance: Social Transformation in Iran from 1500 to the Revolution]. Translated by A. Tadayon. Tehran: Rasa.

Gasiorowski, M. J. 1991 [1371]. Syasate Kharejie America va Shah [U.S. Foreign Policy and the Shah: Building a Client State in Iran] / Translated by J. Zanganeh. Tehran: Rasa.

Gnoli, G. 2016 [1395]. Sheklgiri-e Ideh-ye Iran va Hoviate Irani dar Iran-e Bastan [Idea of Iran: An Essay on its Origin]. In Ashraf, A. (ed.), Iranian Identity from Ancient until the End of Pahlavi (pp. 47–56). Translated by H. Ahmadi. Tehran: Ney.

Haji-Yousefi, A. M. 2005 [1384]. Syasate Kharejie Iran Dar Partow Tahvolate Mantagheh [Foreign Policy of Iran in the Light of Regional Developments]. Tehran: Institute for Political and International Studies.

Hedayat, M. 1965 [1344]. Khaterat va Khatarat [Memoires and Perils]. Tehran: Zavvar.

Hobson, J. M. 2000. The State and International Relations. Cambridge University Press.

Hunter, Sh. 1990. Iran and the World: Continuity in a Revolutionary Decade. Indiana University Press.

Hunter, Sh. 2010. Iran's Foreign Policy in the Post- Soviet Era: Resisting the New International Order. Praeger.

Kinzer, St. 2008. All the Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror. Wiley.

Lambton, A. K. S. 1980 [1359]. Nazarieh Dowlat dar Iran [Some Reflections on the Persian theory of Government]. Translated by C. Pahlavan. Tehran: Azad Book.

Lambton, A. K. S. 1960 [1339]. Malek va Zare dar Iran [Landlord and Peasant in Persia]. Translated by M. Amiri. Tehran: Institute of Book Translation and Publication.

Larijani, M. J. 1990 [1369]. Maghoolati dar Estrategy Melli [Issues in National Strategy]. Tehran: Institute of Book Translation and Publication.

Lenczowski, G. 1977 [1356]. Reghabat Russia va Gharb dar Iran [Russia and the West in Iran 1918–1948: A study in Big-Power Rivalry]. Translated by E. Raeen. Tehran: Javidan.

Mahdavi, A. H. 2005 [1384]. Tarikhe Ravabete Kharejie Iran [History of Iran's Foreign Relations: From the Safavid to the Second World War]. Tehran: Amir Kabir.

Maleki, Kh. 1989 [1368]. Khaterat-e Syasie Khalil Maleki [The Political Memoirs of Khalil Maleki]. Tehran: Sehami Enteshar Corporation.

Mann, M. 1986. The Sources of Social Power, A History of Power from the beginning to A.D. 1760. Vol. 1. London: Cambridge University Press.

Mann, M. 1993. The Sources of Social Power: The Rise of Classes and Nation-States, 1760–1914. Vol. 2. London: Cambridge University Press.

Mann, M. 2012. The Sources of Social Power: Global Empires and Revolution, 1890–1945.Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press.

Mann, M. 2013. The Sources of Social Power: Globalizations, 1945–2011. Vol. 4. Cambridge University Press.

Martin, V. [ed.]. 2005. Anglo-Iranian Relations since 1800. London and New York: Routledge.

Matthee, R., and Andreeva, E. (eds.). 2018. Russians in Iran: Diplomacy and Power in the Qajar Era and Beyond. I.B. Tauris.

Rajaee, F. 2013 [1392]. Moshkeleye Hoviya-e Iranian Emruz [The Problematique of the Contemporary Iranian Identity]. Tehran: Ney.

Rosenau, J. N. 1970. The Adaptation of National Societies: A theory of Political Behavior and Transformation. New York: McCaleb-Seiler.co.

Ramazani, R. K. 1966. The Foreign Policy of Iran: A Developing Nation in World Affairs 1500–1941. University Press of Virginia.

Saikal, A. 2005 [1384]. Syasate Kharejie Iran 1921–1979 [Iranian Foreign Policy 1921–1979]. In Avery, P., and Hambly G.R.G. (eds.), The Cambridge History of Iran (pp. 113–115). Translated by M. Saghebfar. Tehran: Jami.

Sariolghalam, M. 2000 [1379]. Syasate Kharejie Jomhori-e Eslami-e Iran [Foreign Policy of Islamic Republic of Iran]. Tehran: Center of Strategic Research.

Seifzadeh, H. 2005 [1384]. Syasate Kharejie Iran [Foreign Policy of Iran]. Tehran: Mizan.

Zowghi, I. 1989 [1368]. Tarikhe Ravabete Syasi Iran va Ghodrathaye Bozorg 1900–1925 [The History of Diplomatic Relation of Iran and the Great Powers 1900–1925]. Tehran: Pazhang.