The Death of Belonging? Interactions between Neo-Medievalism, Security and National Identity

Journal: Social Evolution & History. Volume 22, Number 1 / March 2023

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/seh/2023.01.04

Justin Gibbins, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Zayed University, Dubai

New medievalism or neo-medievalism challenges the authority and capacity of the state. This weakening or hollowing out of the state has implications most notably for security. This is because a host of actors compete against and adulterate the state's monopoly on violence. Identities are also impacted by neo-medievalism, with multiple, cross-cutting and transnational networks of belonging all becoming more prevalent. However, a neglected area within the literature are the impacts on national identity: the perceived sense of belonging to a nation based on shared culture, memories or institutions. National identity is seen as becoming increasingly obsolete due to the myriad of state challengers. This paper instead argues that neo-medieval security considerations are themselves shaping national identity in different ways. This is addressed by examining the impacts of three such developments: the changing nature of warfare, the increasing role of non-state actors and the prevalence of transnational organizations.

Keywords: national identity, neo-medievalism, organizations, security, states.

INTRODUCTION

Neo-medievalism, born during the superpowerdom of the Cold War in which state-centricity was paramount, seemed to endure a lengthy lull immediately after its inception. As one scholar pointed out, it ‘has led the quiet life of a sleeping beauty’ (Friedrichs 2001: 476). Exploited by some for its ‘conceptual slipperiness’ (Holsinger 2007) and ‘ephemeral’ (Fitzpatrick 2011: 11) in its nature, even its major architect, Hedley Bull, argued that it was states, not transnational, cross-cutting entities, that were responsible for forging an international society (2002: 245). With the theoretical dominance of the idealist/realist prism, neo-medievalism was also relegated early on to an epiphenomenal position. Broadly speaking, Idealism looked towards institutionalism to remedy international anarchy and focused on the constraining capacities of international organizations. Realism continued to privilege the state as the most important actor within the international system and had little need to broaden the political horizons to include the plethora of supra-state and sub-state actors to help understand the international system.

The post-Cold War epoch has witnessed a resurgence. Neo-medievalism fits well into the various strata of a political world no longer anchored to the machinations of two hegemonic powers. At the domestic level, it captures a disintegrated world order in which state authority, as seen in weak and failed states, is challenged by competing sources of internal and external power. At the regional level, some institutions have evolved into ‘imperial conglomerates’ (Khanna 2009) with political, monetary and legal powers that transcend states in many areas. At the international level, neo-medievalism captures the embedded interdependence and transnationalism in which a host of international actors – non-governmental organizations, intergovernmental organizations, multinationals as well as other entities – vie for influence. At all stages, neo-medievalism fundamentally ushers in change, wherein established loyalties abate, and new ones emerge. With regard to Hedley Bull’s original typology, there are five categories in which neo-medievalism plays out: the technological unification of the world, the regional integration of states, the disintegration of states, the rise of transnational institutions and the resurgence of private international violence (Bull 2002: 245). As such, it is the aspects attached to both security and the economy that are most being transformed.

As ‘a system of overlapping authority and multiple loyalty, held together by a duality of competing universalistic claims’ (Friedrichs 2001: 475), neo-medieval sub-state and supra-state entities are reflective of both the disaggregated and fragmented world as well as the harmonized and globalized one. The wealth of studies available is emblematic of its revival. Its conceptual power has been applied to individual states such as Hungary (Deets 2008), Sri Lanka (Norell 2003), Bosnia (Simms 2003) and Malta (Brommesson 2008). Its dynamics have been explored within the immediate literature produced after the September 11, 2001 attacks (Berzins and Cullen 2003) as well as militant groups which exemplify a common neo-medieval circumstance: when a state loses its monopoly on violence, sub-state actors flourish (Klauck 2017; Ünay 2017). Additionally, neo-medie-valism has also been applied to the digital domain in which the shift from a modern to a postmodern political economy is as seismic as the historic move from the medieval to the modern era (Kobrin 1998). As a non-traditional polity, the European Union has also been investigated with regard to its fuzzy borders (Angelescu 2008) and its increased regional grand strategy rather than global approach (Winn 2019).

However, national identity, the perceived sense of belonging to a nation reflected in various shared traditions, culture, institutions, history and language, is a neglected aspect within neo-medievalism. There are three reasons for this. Most basically, national identity does not fit into the fragmented, regionalized and globalized identities that are symptomatic of changing political actorness. On the one hand, sectarian identities are flourishing with over 100 secessionist movements worldwide (Kingsbury 2017) with even strong states like India and China marred by nationalist movements that position ethnic and cultural identities in opposition to the broader state in which they operate. On the other hand, the pull of mega institutions weakens national identities by positioning them in a network of many. In short, national identity is being pushed and pulled from inside and out. Secondly, national identities are anachronistic and symptomatic of an attachment that no longer reflects the postmodern world. With regard to the prevalence of multiple loyalties and identities, Czerny argues that neo-medievalism:

… has often come under fire from ‘inter-nationalists’ and believers in the continuing strength of deeply embedded national identities. However, I would argue that the fragmentation of identities will basically cut across, coexist and overlap with pre-existing national identities, although the latter will become increasingly empty rituals divorced from real legitimacy, system affect or even instrumental loyalty (Czerny 1998: 55–56).

Similarly, the Italian philosopher and critic Umberto Eco located neo-medievalism as ‘transformation between the end of a world-wide empire and the rise of a new political balance – a very pluralistic period in which the whole deck of historical cards is shuffled and no nostalgia for the past is allowed’ (Eco 1987). National identities are a bygone belonging, no longer capable of competing with the wealth of identity challengers that are anathema to holistic images of the nation. Thirdly, the host of sub-state actors has weakened the state’s ability to formulate a dominant and subsuming identity. Obvious examples include how the global norms of human rights (e.g., Bailliet 2012) and climate change (e.g., Hale 2018) have been influenced by sub-state actors. As such, states are less norm entrepreneurs and more vehicles for sub-state norm creators to fashion a rules-based world. National identities have simply become a means to an end.

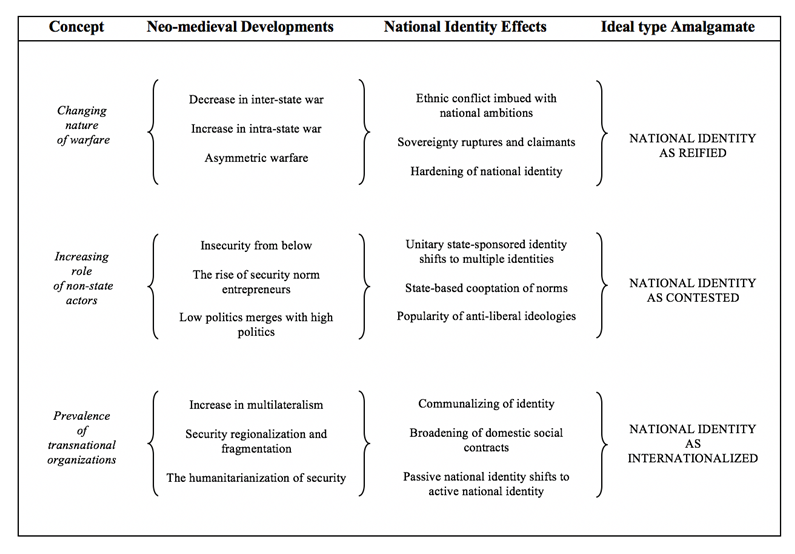

From a methodological standpoint, this paper defines neo-me-dievalism as a concept that can help us make sense of certain security dynamics rather than taking neo-medievalism to be an actual paradigm that can be subject to analysis within international relations. The aim is to argue how national identity, rather than fading away due to the presence of neo-medievalism, is actually being reformulated in a number of ways. It is not suggested that the reformulations presented are the only or necessarily the most important ones. I instead argue that via a careful reading of the available literature, these outcomes are nonetheless tangible and empirically supported, and the findings simply help us to understand the relationship between neo-medievalism and national identity better. The following are discussed: the fluctuating nature of warfare, the growing importance of non-state actors and the predominance of transnational organizations. Each is discussed in two ways. First, I explain how each concept can be characterized by three neo-medieval developments. Second, I explore three national identity effects stemming from these impacts. This empirical section is introduced with Figure 1 which synthesizes the findings. The paper concludes with a summary of how the influences on national identity can be systematized through ideal type amalgamates. In this section, I also briefly discuss the importance of framing neo-medievalism and national identity not as zero-sum game challengers but as a series of interrelationships.

THE CHANGING NATURE OF WARFARE

An obvious neo-medieval impact on security is the shifting nature of conflict. Within this concept, three developments are apparent. First is the decline-of-war thesis (see, e.g., Angell 1911; Levy 1983; Holsti 2006; Goldstein 2011). The hypothesis broadly argues that the costs to war simply outweigh whatever benefits accrue, irrespective of whether conflict is motivated through territorial conquest, the acquisition of resources, personal ambition or ideological differences. Varying time periods appear to tell the same story. Levy (1983) analyzed the declining trend between conflicts between great powers from 1495 to 1975 and argued that the ‘increasing costs of Great Power war relative to its perceived benefits have reduced its utility as a rational instrument of state policy and largely account for its declining frequency’ (1983: 14, cited in Sarkees et al. 2003: 51). Tertrais, reporting on Uppsala Data Conflict Project (UDCP) and Center for Systemic Peace (CSP) data, also concludes that classic international conflict has practically disappeared despite the tripling of the number of states since 1945 (Tertrais 2012: 9). A second trend of warfare is the shadow impact of a spike in civil or intrastate conflicts during the post-World War Two period (Dupuy and Rustad 2018; Dosse 2010). Between 1945 and 1999, approximately 3.33 million battle deaths occurred in 25 interstate wars with a minimum of 1000 dead overall in contrast to 16.2 million deaths within 127 civil wars (Fearon and Laitin 2003: 75). These two developments are of course, by no means uncontested (see, e.g., Fazal 2014), although neo-medievalism offers a number of explanations. They include the internalization of norms (Talentino 2005: 4); leaders and people rather than democracy becoming more war averse (Human Security Report 2015: 150); and the argument that traditional conflict is waning and ‘new wars’ are being forged with a mixture of war, organized crime and human rights violations conducted by global, local, public and private actors (Kaldor 1999). Relatedly, the third aspect of conflict is asymmetric warfare becoming the custom due to the state no longer being the only or indeed the central orchestrator of violence. A shadowy term, asymmetric warfare was first utilized to examine how big nations lose small wars, with insurgents regarding the conflict as ‘total’ but the external power treating it as ‘limited’ (Mack 1975: 181). Within civil wars, violent non-state actors seem to be not bound by the laws which govern states (Lele 2014: 105) and this provides an attractive incentive for non-state groups to engage in terrorism, insurgency and organized crime. Asymmetric intra-state warfare has historically emboldened militarily weaker units with the capacity to break the political will of dominant states to fight. Military methods, rather than military size, can win wars. Neo-medievalism also broadens actor-centrism. Local voices, military bases, autonomous territories and secessionist groups, for example, can also mold state security (Taka-hashi et al. 2019).

Fig. 1. Neo-Medieval Developments and National Identity

To summarize, neo-medievalism has produced three noticeable changes within warfare: the decrease in inter-state war, the increase in intra-state war and the proliferation of asymmetric warfare. These, in turn, are responsible for a number of national identity impacts. The first is the manner in which ethnic conflict becomes imbued with national characteristics. Ethno-nationalism places the concept of the na-tion – common linkages of culture, language, myths or history – as being defined ethnically. As the ethnic group is a community of people, kin survival is logically compelled by self-determination and self-government. As Gurr (1993) points out, the rise of nationalism in the modern period combined with the ‘problem of fit’ with 600 language groups, 5000 ethnic groups and fewer than 200 states (cited in Woods et al. 2011: 154), leads to factions vying for political legitimacy. Ethnic conflict is often characterized as a national struggle. The demise of colonial wars, coupled to the de-ideologization of conflicts due to the end of the Cold War, has catapulted ethnicity as a principal reason for conflict. Claims for statehood have tended to be legitimized via nationalism and the post-colonial break up which spawned an increase in the number of states has led to many ethnic claims over national governance (Rubinoff 2000: 273.) Additionally, the principle of self-determination, enshrined within international law via Article 1 of the United Nations Charter as well as the 1960 Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, has similarly linked ethnicity to statehood. The norm of self-determination has galvanized ethnic groups, perhaps most notably in weak and fragile states, to vie for political representation. Finally, conflict at an ethnic level can exacerbate the degree of violence being carried out. In the most extreme cases, within genocide for example, methods such as categorization, discrimination, dehumanization, persecution and eventual extermination, are framed and justified due to the out-group being an existential threat. The entity most invested with this responsibility is the state and tyrannical governments therefore often frame ultra-nationalistic and hyper-militarized identities as a mechanism to oppress ethnic groups which themselves are seen as a threat to the nation.

The second effect on national identity stemming from the shifting nature of warfare is the advent of sovereignty ruptures and the proliferation of new claimants. The rupture of sovereignty ‘results from the violent contest between the governing authority and its opponents constitutes the core feature of civil war’ (Sambanis and Schulhofer 2019: 1547). Taking Krasner’s definition of sovereignty as ‘the assertion of final authority within a given territory’ (1988: 86), conflict, especially at the ethnic level, involves clashes over national identity and are characterized by which group gets to usher in the new zeitgeist of the nation. The emphasis here, however, is the zero-sum game nature of sovereignty and the manner in which it has been used to ‘beat the competition’:

In situations of existential competition, success by one is likely to spell the demise of the other. In situations of non-existential competition, a gain by one means a loss by the other. In such situations, political entities use the tool of sovereignty to beat the competition because the legitimacy that sovereignty confers makes it one of the more potent tools in their toolbox (van Veen 2007: 9).

Sovereignty is wedded to both internal and external legitimacy. Internally, it places one group as the dominant benefactors in the power grab for the state. Externally, the body that claims sovereignty becomes recognized by other sovereign states and this enables them to utilize the diplomatic, commercial and international legal ties that are the benefits of statehood. What is more, sovereignty claimants do not always take the guise of ethnic groups because sovereignty is linked to a neo-medieval fanning out of actors not defined by any single ethnic group but by a multiplicity of agents. For example, tensions can exist between elite sovereignty and popular sovereignty with no ethnic distinction being the cause. Coup d’états also seem to be a common albeit declining form of sovereignty challenge with the 2010–2019 period having 47 unrealized coups and 13 realized ones; 2000–2009, 43 and 23; 1990–1999, 73 and 62; 1980–1989, 93 and 65; and 1970–1979, 88 and 93 (Peyton et al. 2021). In short, there seems no shortage of sovereignty claimants within the fragmented neo-medieval framework.

The third warfare-related effect is the hardening of national identity. Rather than waning, national identity can become more impervious. On a national level, the spike in sovereignty competitors certainly might seem to disaggregate identity on a homogenous nationwide level. However, two reflections are apparent. For some conflicts, national identity is central for three reasons: as an end in itself as identity creates belongingness for the group, as the ultimate justification of the group’s land and resource claims, and as a means to provide a focus for advancing the group’s culture, religion and customs (Kelman 2001: 191). With reference to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, for instance, ‘acknowledging the other’s identity becomes tantamount to jeopardizing the identity – and indeed the national existence – of one’s own group’ (Kelman 2001: 192). As national identity functions as a tool for group survival, its constituent components become more extreme and unyielding. ‘Soft’ national identity, one might argue, has more fluid boundaries and might be synonymous with non-violent nationalism. Scottish and Catalan national identities might be representative of this kind. ‘Hard’ national identity has more rigid boundaries, with little interest in accommodating the opposing identity. The destructive implications might lead to an ‘authoritarian’ identity which pitches opposing identities as existential threats. The second reflection on the hardening of identity is whether or not the group functions as a majority or minority. Korostelina in her study of the impact of national identity on conflict with regard two ethnic minorities in Crimea, concluded Russians who adopt a national identity and who believe they are the dominant group will be more inclined to engage in violence against other ethnic groups whereas Crimean Tatars who identify with national identity are more inclined to configure Ukraine as a multinational rather than an ethnocentric nation (Korostelina 2004: 225–6). If one minority feels it is linked to a more dominant national identity, say evident within an adjacent ‘great power’ state, then expressions of national identity might be more prone to violent expression. National identity hardens not merely as a precursor for conflict but also as a product of conflict.

THE INCREASING ROLE OF NON-STATE ACTORS

A second focus of neo-medievalism concerns the burgeoning role of non-state actors within international as well as domestic security. Westphalianism historically wedded security to the state and the corresponding security dilemma has become more obsolete. As Zielonka identifies:

The Westphalian state is about concentration of power, hierarchy, sovereignty and clear-cut identity. The neo-medie-val empire is about overlapping authorities, divided sovereignty, diversified institutional arrangements and multiple identities. The Westphalian state is about fixed and relatively hard external border lines, while the neo-medieval empire is about soft border zones that undergo regular adjustments (Zielonka 2014: 81).

There are three aspects to the increasing role of non-state actors. The first concerns what can be called ‘insecurity from below’ (Czerny 1998: 39). The state has become one of several oligopolistic security competitors. As Czerny goes on to clarify, ‘the rise of civil wars, tribal and religious conflicts, terrorism, civil violence in developed countries, the international drugs trade’ all indicate that:

A kind of generalised ‘insecurity from below’ has emerged, bound up with the dual character of globalisation as a global-local dialectic, whipsawing the state between the international and transnational, on the one hand, and an increasingly complex set of micro- and meso-level phenomena on the other – what Rosenau has called ‘fragmegration’ (Czerny 1998: 39).

The second development is the rise of security norm entrepreneurs. Power diffusion has created a panoply of sub-state security actors. Cybersecurity is a pertinent area to locate this trend. Glen, for example, identifies three clusters of agents shaping this issue: traditional international diplomacy carried out by national governments; multi-stakeholder entities which include civil society, businesses, research institutions, governments and NGOs; and the private sector dominated by technology companies (Glen 2021: 1127–8). States, of course, still continue to have a dominant role within the proliferation of security norms such as in nuclear weapon non-use or in sovereignty. However, the neo-medieval collage results in middle-power and small-power states having a more pioneering role. For instance, Australia and the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) (Ralph 2017), Chile and international human rights (Fuentes-Julio 2020) and Sweden and conflict prevention (Björkdahl 2007). What is more, these state-centric responsibilities towards norms are themselves influenced by public discourse, domestic civil society and broader citizen-driven NGO linkages. A final aspect concerning the growth of non-state actors is the manner in which low politics has molded into high politics. It is, of course, well established that state security has incorporated human security since World War Two. This has broadened the dimensions of security in a wide array of areas. New security threats including water, food and energy security; gender-based violence; global health threats; migration; religious extremism and terrorism; organized crime and human trafficking; cyber threats and populism (Gueldry et al. 2019). These challenges forge new modes of global governance necessary to deal with them:

If government denotes the formal exercise of power by established institutions, governance denotes cooperative problem-solving by a changing and often uncertain cast. The result is a world order in which global governance networks link Microsoft, the Roman Catholic Church, and Amnesty International to the European Union, the United Nations, and Catalonia (Slaughter 1997: 184).

To recap, the increasing role of non-state actors has three impacts: insecurity from below, the rise of security norm entrepreneurs and the forging of low politics into high politics. Stemming from these, national identity is fashioned in several ways. The first is how unitary state-sponsored identity, due to bottom-up pressures, shifts to multiple identities. The state may retain a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence but is not the sole authority on purveying national identities. However, it is worth noting that democracies are more prone to national identity fractures than non-democracies. As argued by Fukuyama:

Globalization has brought rapid economic and social change and made these societies far more diverse, creating demands for recognition on the part of groups that were once invisible to mainstream society. These demands have led to a backlash among other groups, which are feeling a loss of status and a sense of displacement. Democratic societies are fracturing into segments based on ever-narrower identities, threatening the possibility of deliberation and collective action by society as a whole (Fukuyama, n. d.).

The assertion of new groups accompanied by the corresponding backlash from others can be seen as clashes over national identity. Within the United States, it has been argued how the weakening of classical American nationalism, and the consequent loosening of the connections of mutual loyalty, has created a vacuum at the core of American national identity (Hazony 2018). Additionally, the Pew Research Center analyzed attitudes in the U.S., France, Germany and the U.K. and concluded that the criteria for national belonging – being born in the country, sharing national customs, being Christian and speaking the national language – have become less strict for many over the 2016–2020 period polled (Silver et al. 2021). The waning of old identities ushers in new forms of belonging. These, of course, can produce notable tensions. Within Brexit, the UK decision to leave the EU after its 2016 referendum, national identity issues over sovereignty, immigration and democracy were paramount. Cultural pluralism, with government multicultural policies designed to integrate rather than assimilate, and with backlash against this model due to race riots and the terrorism of 9/11 and 7/7, certainly functioned as a motivator for Brexit, it has been argued (Ashcroft and Bevir 2016: 356). The crisis of multiculturalism also permeates other European states. To coin the identity dilemma, as one scholar articulates, ‘in the past, groups perceived as incompatible with European identity were usually located beyond European borders. But now they are firmly established within Europe itself’ (Chin 2017: 2).

A second development is the state-based cooptation of norms. The lifecycle of norms evolves from a process of creation, diffusion and internalization and it is an understandable focus that international norms have impacted on the domestic make-up and identities of states. That is to say, domestic identities have been shaped by international forces. However, the role of norm entrepreneurs, and their ability to foment the norm which eventually becomes elevated from the local, to the national, to the global level, is key. Motivated by altruism, empathy and ideational impetuses, and strategized through persuasion and activism, ‘norm entrepreneurs are critical for norm emergence because they call attention to issues or even ‘create’ issues by using language that names, interprets, and dramatizes them’ (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998: 897). Of course, the abolitionist movement, the International Committee of the Red Cross, labour rights and women’s suffrage all predate the appearance of neo-medievalism. However, post-World War Two norm proliferation indicates the increasing power of norm galvanizers. Risse and Sikkink argue how human rights norms have been established through a network of advocacy groups which serve a threefold purpose: they raise moral consciousness against norm violators, they empower and protect domestic resistance to norm breakers, and they create a transnational structure which pressures repressive regimes (Risse and Sikkink 1999: 5). However, in order to consolidate norms, whether via realist raw self-interest, liberal institutionalization or constructivist socialization, states are essential for this process of consolidation. This is because states alone have the capacity to municipalize the norm so it becomes embedded at a national level and then a component of national identity. Additionally, only states possess the legalistic wherewithal to reinforce the norm through legal means by making the norm law via treaties or via constitutional amendments. Modern states embed norms because modern states are expected to carry out certain functions. Examples of common organizational structures and practices include policy planning, the principles of science and the promotion of public welfare (Goodman and Jinks 2008: 728). As such, neo-medievalism results in states being buffeted both bottom-up by pressures coming from NGOs and local norm advocates as well as top-down pressures from IGOs and advocacy networks with international linkages.

A final observation springing from the increasing role of non-state actors is the popularity of anti-liberal ideologies. As highlighted in a recent Foreign Affairs article:

Populist politicians across the globe call for major changes in the norms and values of world politics. They attack liberal order as a so-called globalist project that serves the interests of sinister elites while trampling national sovereignty, traditional values, and local culture (Cooley and Nexon 2021).

On the face of it, what might be labelled a nativist spike seems anti-medieval: that political elites via anti-democratic measures are centralizing their authority in a manner more reflective of the unabashed power of the state. An analysis of illiberalism in Turkey, Poland and Hungary, as well as encroaching elements within the Czech Republic and Slovakia, highlights the decline of liberal principles based on individual liberties, minority rights and separation of governmental powers, as well as democratic structures essential for linking popular will to public policy (Polyakova et al. 2019: 2). However, there are three factors worth highlighting which link neo-medievalism to illibe-ralism and then to national identity. First, liberal tenets such as expansive images of national identity that capture all citizens within the polity irrespective of their ethnic, religious or political identity, tend to be undermined by illiberal leaders (Polyakova et al. 2019: 5). Liberalism itself is configured as a threat to citizens, and populist leaders who promote nationalism through the privileging of specific ethnic and religious identities therefore position themselves as vanguards or protectors of what are seen as weakened, formally dominant ethno-cultu-ral traditions. Second, neo-medievalism has effectively weakened the ability to create pan-national identities because the proliferation of non-state actors also has a voice in shaping the national psyche. This flux and destabilization have catapulted populist leaders into a position of defenders of traditional national identity. For instance, eastern and central European populism, it has been argued, has been aggravated by the ‘fear of diversity and fear of change, inflamed by the utopian project of remaking whole societies along western lines’ (Krastev and Holmes 2019). Finally, the manner in which low politics has become high politics has placed national identity issues at the forefront of ideology. The most obvious articulation of right-wing identity-based ideology is how mass immigration is the principal threat to national identity. However, as cultural rather than economic cleavages have become more dominant, ‘immigration has added non-economic significance to the right-left distinction’ which helps explain working-class support for far-right parties (Kopyciok and Silver 2021: 4–5). A mistrust of globalism and the authorities who are responsible for it often creates bedfellows of elements of the left and right. Both tend to configure established elites as having hijacked the nation for their own interests, and more established, historically embedded practices of national identity, as they are planted at the popular level, are invoked and utilized to create resistance to this process.

THE PREVALENCE OF TRANSNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS

The final aspect of neo-medievalism is the increasing prevalence of transnational organizations. Although the term usually refers to international non-governmental organizations which transcend the nation-state, this section instead focuses more on intergovernmental organizations. Again, three impacts can be addressed. The first is the primacy of multilateralism. Not merely is multilateralism characteristic of a neo-medieval world within which many spheres of influence flourish and necessitate cooperation through burden-sharing, but unilateralism is becoming increasingly dangerous and vilified. Unilateralism may well satisfy short-term goals but can lead to long-term harm to the state’s reputation even if it is regionally hegemonic. For example, out of ten inter-state conflicts from 1990 to 2010, only two were not addressed by the United Nations Security Council (Fox 2014: 243). The UN is also a transitioning actor in aiding the shift from conflict to peacetime governance via post-conflict reconstruction (Fox 2014: 244). With the advent of United Nations sanctions, International Court of Justice rulings as well as the past record of the International Criminal Court and Tribunals, unilateralism can, at least for some, produce a high cost to governments. A second development within security organizations is the dual paradox of security regionalization and fragmentation. Regionalization has understandably flourished within a post-Cold War world. In a review paper, Kelly distills several variables associated with regionalism which contrast with global structures and fits in well with neo-medieval power diffusion (2007: 198 and 223–4). Security issues at the local level form regional dynamics and in-ternational organizations designed to deal with them while weak and failing states turn the security dilemma inward and produce, according to various theorists, IOs which enforce domestic sovereignty and ignore internal repression. Fragmentation takes several forms including the manner in which security has effectively been outsourced which, according to some, shows an increasing unwillingness to deal with conflict resolution (see, e.g., Gowan and Witney 2014). Within institutions themselves, private security companies and contractors have mushroomed. Reasons include the security gap with a proliferation of failed states, terror groups and revived quarrels; globalization causing a surge in trade which has widened the gap between state actors; new modes of warfare in which military technologies have enabled civilian companies to flourish; and privatization in which markets are being more dominated by the activities of non-state actors (Pałka 2020: 5–6). A final feature of transnational security organizations is the humanitarianization of security. Post-World War Two human security has been spearheaded by international organizations. As one scholar noted:

Not only did the last century see the emergence of regimes committed to the physical destruction of populations but also of entities devoted to monitoring and assisting populations in maintaining their physical existence, even while protesting the necessity of such an action and the failure of anyone to do much more than this bare minimum (Redfield 2005: 329).

Humanitarianization has developed in a number of ways. International humanitarian legal norms have become omnipresent with basic principles of military necessity, precaution, distinction and proportion being codified within legislation as well as the emergence of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine. The United Nations security framework has increasingly been shaped by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Additionally, agencies have shifted from being aid providers to dealing with the actual causes of conflict. Also, humanitarian arguments have simply become more dominant within international security discussions (Reid-Henry and Sending 2014: 431 and 434).

To sum up, the increase in multilateralism, security regionalization and fragmentation, and the humanitarianization of security all stem from the increasingly dominant role played by transnational security organizations. In relation to the impacts on national identity, the first is the communalizing of identity. Rather than hard-bordered, territorially defined conceptualizations of security, states have become more inclined to socialize their security with regard to others. A logical outcome of this has been the fruition of security communities. Most associated with Karl Deutsch, security communities are a group of integrated people, attaining a sense of continuity of institutions and practices, and united by a sense of agreement that common problems can be resolved through peaceful change without the use of large-scale force (Deutsch et al. 1957: 5). Security communities can communalize national identity in two main ways. The first is the benefits attached to the cooperation between common identities. As security communities are predicated on the notion of integration, national identity plays a role in forging interdependence. This is because ‘integration is achieved when there is a prevalence of mutually compatible self-images of the states participating in the process, up to the point of developing a common identity and mutual expectations of shared economic and security gains’ (Kacowicz 1999: 542). Such shared identities can include political systems, namely democratic values and institutions, but also common language, history and geography. The second is the importance of the commonality of goals. Countries with shared histories are more inclined to configure externalities in the same way. It is, of course, by no means a uniform process but security communities can act as a tool for coagulating opinion to produce common responses to common problems. As an example, in the Community Vision for 2025, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations stresses ‘an inclusive and responsive community that ensures our peoples enjoy human rights and fundamental freedoms’ and ‘a community that embraces tolerance and moderation, fully respects the different religions, cultures and languages of our peoples, upholds common values in the spirit of unity in diversity’ (ASEAN 2015: 4). Transnational institutional change also impacts on security communities and identity. Attitudes to the nation, patriotism and ethnic identity, have a level of resilience due to globalization pushback, path-dependency and historical legacy. Globalization seems to function as the backdrop to social, cultural and national changes which are deprioritized for more here-and-now national sentiments and priorities. For example, the real or potential loss of territory/sovereignty or existence of geopolitical threats leads to higher support for restricting immigrants from non-dominant groups (Ariely 2019: 776). As such, neo-medieval patterns of globalization become one more piece in the national identity puzzle with contested multiple loyalties producing both global as well as national citizens depending on other influences.

Secondly, transnational organizations have influenced the broadening of domestic social contracts. Social contracts define the relationship between the individual or group and the government and include such values as security, freedom and welfare. Neo-medieval security regionalization and fragmentation, as well as the humanitarianization of security, have enabled externalities to reshape the social contract. National contracts respond to global concerns. Naturally, such linkages are difficult to attain as there is no formal contract between citizens and an imaginary global authority, but national governments are being held accountable for their ability to provide global public goods (Derviş and Conroy 2019). Examples might include the reduction of carbon emissions as well as the abolishment of nuclear weapons. Of course, universality within international law is an increasingly difficult ideal to work towards but that is not the point. The issue is how global fears help shape national identities. Additionally, such processes occur due to weak domestic social contracts which are more inclined to be substituted with global ones. Fragile domestic contracts can be revealed through citizens’ trust of governments. According to the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development, of the 40 countries listed, 13 have seen lower trust levels in 2020 than in 2010 and 25 have trust levels of lower than 50 per cent (OECD 2022). Other data indicate how trust in the political systems of European nations is markedly low, with Pew Research Center indicating that trust in the US government is at a historic nadir (Ortiz-Ospina and Roser 2016). Arguably, a lack of faith in domestic government is causing citizens to turn to alternatives. As a United Nations Development Programme reports mentions:

International covenants, security pacts, trade regimes, financial agreements, governance institutions, social movements and forces, all add concrete boundaries and pressures to the eventual shape and reach of a national social contract. Although national actors may have the feeling that they are involved in their own negotiations, existing supranational structures and forces may greatly reduce the space for maneuver and may influence the result of those negotiations (UNDP 2016: 13).

As such, international organizations help fossilize international concerns within domestic social contracts.

A final consideration concerns how the neo-medieval impacts of transnational organizations shape national identity from being a passive to an active entity. I take passive national identity as being similar to everyday reproductions of nationalism (e.g., Billig 1995; Déloye 2013). This taken-for-granted process sees nationalism produced through, for example, media, symbols on money, literature, sport, and so on. Unlike the more commonly studied extremist nationalisms, which precisely because of their radicalism sit outside of the boundary of mainstream invocations of national identity, passive national identity is a grassroots rendering of largely unconscious social acts which solidify themes into the nation. Active national identity is more about change. Identity ruptures cause individuals to reevaluate the established national identity being lost or the new one emerging. For example, the current refugee crisis caused by the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine is testing how humanitarian European states’ really are. Of course, transnational civil society also humanitarianizes national identities. NGOs are particularly vibrant within democracy promotion as they ‘enhance democracy by expanding the number and range of voices addressing government’ (Silliman and Noble 1998: 306). As such, the fanning out of actors, particularly with regard to transnational organizations and the humanitarianization of security, activates national identity by injecting human security issue areas into the national vision and helps popularize and foment such concerns abroad.

CONCLUSION

This paper has argued that national identity, despite claims of its gradual obsolescence due to the fragmentation and globalization implicit within the enveloping neo-medieval order, actually functions as a shapeshifter. The various impacts on national identity, as shown in Figure 1, can be categorized according to ideal types to aid examination.

Within the changing nature of warfare, national identity is reified. Ethnic identity frequently becomes imbued with national ambitions because the acquisition of sovereignty is the best way to enable the ethnic group to realize its goals. The spike in sovereignty ruptures and claimants indicates that both intrastate and interstate conflicts still continue to be framed within the desire for nationhood. Additionally, to galvanize citizens in a struggle, to imbue a solid sense of belonging, and to absorb various historical, emotional and cultural strands into a composite whole, national identity becomes hardened.

With regard to the increase in non-state actors, national identity is contested. Unitary state-sanctioned national identity is being challenged by sub-state and civil society actors. Alternative visions of national identity are constantly jostling for supremacy within the narrative of nations. Norm entrepreneurs are also shaping the identity of nations and states coopt norms once a critical mass has been reached in order to both claim ownership and to legitimize them. Anti-liberal ideologies have also become part of the neo-medieval patchwork. A mistrust of established political and economic elites as well as certain political and economic projects reflective of globalism have created tensions within states about traditional national identities being besieged.

In terms of the rise of transnational organizations, national identity is internationalized. The communalizing of identity is a product of security arrangements that are becoming more multilateralized and regionalized. Common goals and values socialize security considerations. Weak domestic social contracts coupled with global fears enable citizens to search for social contracts from outside of their national domain. Passive national identity, reproduced in an everyday manner, is being challenged by more active national identity which incorporates transnational groups as an important vehicle to shape and internationalize domestic concerns which are less and less likely to operate in a territorially bound bubble.

In conclusion, there are three important advantages worth highlighting with regard to neo-medievalism, national identity and the study of their relationship. Firstly, even if nation-statism is under siege from neo-medievalism, the fact remains that national identity is ‘sticky’ and ‘sedimented over time’ (Norval 1999: 84). National identity changes but seldom disappears. And even its disappearance produces new entrants. As such, rather than examining national identity as a state-mandated, uniformed block of meaning, the interrelationship between neo-medievalism and national identity captures both stasis and change within a country’s national image. Secondly, no epoch is without challenges and the current one might be marred by the same cleavages and threats as emerged in the early post-Cold war period. As the philosopher Pierre Hassner articulated nearly three decades ago:

Peace or war? Utopia or nightmare? Global solidarity or tribal conflict? Nationalism triumphant or the crisis of the na-tion-state? Progress on civil rights or persecution of minorities? New world order or new anarchy? There seems to be no end to the fundamental dilemma and anguished questions provoked by the post-Cold War world (Hassner 1995: 215).

Looking at neo-medievalism and identity as an interrelationship captures the actors involved, be they part of the fragmented world of non-state actors, the state-centric world of states or the globalized world of transnational organizations, and the impacts they have in terms of the challenges that buffet nations. Finally, security challenges shape nations’ sense of themselves which impacts on how they behave. Whether national identity is reified, contested or internationalized influences the manner in which the state deals in its relations with others. An identity-reified state will be more inclined to address problems through the lens of state power because the national identity of such a state is heavily attached to state-centric concepts such as self-determination and sovereignty. An identity-contested state will be more disposed to approaching problems in a disintegrated and contradictory manner as the panoply of sub-state actors shape the state’s reaction to the issue being addressed. An identity-internationalized state will logically be more prone to multilateralize its interactions and to galvanize its agency through collective action. Who a nation is shapes what a nation does, and the utilization of the dynamics of neo-medievalism, lodged most logically within the constructivist approach, can help our understanding of the linkages between national identity and international relations.

REFERENCES

Angelescu, I. 2008. On Neo-Medievalism, Migration and the Fuzzy Borders of Europe: A Critical View of the Schengen Convention. Europolis, Journal of Political Science and Theory, 3: 44–64.

Angell, N. 1911. The Great Illusion: A Study of the Relation of Military Power in Nations to their Economic and Social Advantage. 3rd edition. New York and London: G.P. Putnam’s & Sons.

Ariely, G. 2019. The Nexus

between Globalization and Ethnic Identity:

A View from below. Ethnicities, 19 (5): 763–783. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796819834951.

ASEAN. 2015. ASEAN Community Vision 2025. URL: https://www.asean.org/wp-content/uploads/images/2015/November/aec-page/ASEAN-Commu-nity-Vision-2025.....

Ashcroft, R., and Bevir, M. 2016. Pluralism, National Identity and Citizenship: Britain after Brexit. The Political Quarterly 87 (3): 355–359. URL: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12293.

Bailliet, C. (ed.) 2012. Non-State Actors, Soft Law and Protective Regimes: From the Margins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Berzins, C., and Cullen, P. 2003. Terrorism and Neo-Medievalism. Civil Wars 6 (2): 8–32. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/13698240308402531.

Björkdahl, A. 2007. Swedish Norm Entrepreneurship in the UN. International Peacekeeping 14 (4): 538–552. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13533310701427959.

Billig, M. 1995. Banal Nationalism. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Brommesson, D. 2008. Neo-Medievalism from Theory to Empirical Application: The Order of Malta as a Model. Internasjonal Politikk 66 (4): 615–632.

Bull, H. 2002. The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics, 3rd edition. New York: Columbia University Press.

Chin, R. 2017. The Crisis of Multiculturalism in Europe: A History. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cooley, A., and Nexon, D. H. 2021. The Illiberal Tide: Why the International Order is Tilting toward Autocracy. Foreign Affairs, March 26. URL: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2021-03-26/illiberal-tide.

Czerny, P. G. 1998. Neomedievalism, Civil War and the New Security Dilemma: Globalisation as Durable Disorder. Civil Wars 1 (1): 36–64. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/13698249808402366.

Deets, S. 2008. The Hungarian Status Law and the Specter of Neo-medieva-lism in Europe. Ethnopolitics 7 (2–3): 195–215.

Déloye, Y. 2013. National Identity and Everyday Life. In Breuilly, J. (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the History of Nationalism [online]. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199209194.013.0031.

Derviş, K., and Conroy, C. 2019. How to Renew the Social Contract. Project Syndicate, June 24. URL: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/democracies-renew-social-contract-two-challenges-by-kem....

Deutsch, K. W., Burrell, S. A., Kann, R. A., Lee Jr., M., Lichterman, M., Lind-gren, R. E., Loewenheim, F. L., and Van Wagenen, R. W. 1957. Political Community and the North Atlantic Area: International Organization in the Light of Historical Experience. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dosse, S. 2010. The Rise of Intrastate Wars: New Threats and New Methods. Small Wars Journal, August 25. URL: https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/the-rise-of-intrastate-wars.

Dupuy, K., and Rustad, S. A. 2018. Trends in Armed Conflict, 1946–2017. Conflict Trends. Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO).

Eco, U. 1987. ‘Dreaming of the Middle Ages’: An unpublished fragment. Semiotica 63 (1–2): 239–239. URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1987.63.1-2.239.

Fazal, T. M. 2014. Dead Wrong? Battle Deaths, Military Medicine, and Exaggerated Reports of War’s Demise. International Security 39 (1): 95–125. URL: https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00166.

Fearon, J. D., and Laitin, D. D. 2003. Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War. The American Political Science Review 97 (1): 75–90. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3118222.

Finnemore, M., and Sikkink, K. 1998. International Norm Dynamics and Political Change. International Organization 52 (4): 887–917. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2601361.

Fitzpatrick, K. 2011. (Re)producing (Neo)medievalism. In Fugelso, K. (ed.), Studies in Medievalism XX: Defining Neomedievalism(s) II (pp. 11–20). Woodbridge, Suffolk; Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer.

Fox, G. H. 2014. ‘Navigating the Unilateral/Multilateral Divide’. In Stahn, C., Easterday, J. S., and Iverson, J. (eds.), Jus Post Bellum: Mapping the Normative Foundations (pp. 229–258). Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Friedrichs, J. 2001. The Meaning of New Medievalism. European Journal of International Relations 7 (4): 475–501. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066101007004004.

Fuentes-Julio, C. 2020. Norm Entrepreneurs in Foreign Policy: How Chile Became an International Human Rights Promoter. Journal of Human Rights 19 (2): 256–274. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/14754835.2020.1720628.

Fukuyama, F. n. d. Against Identity Politics. The Andrea Mitchell Center for the Study of Democracy, PA. URL: https://amc.sas.upenn.edu/francis-fukuyama-against-identity-politics.

Glen, C. M. 2021. Norm Entrepreneurship in Global Cybersecurity. Politics & Policy 49 (5): 1121–1145. URL: https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12430.

Goldstein, J. S. 2011. Winning the War on War: The Decline of Armed Conflict Worldwide. New York: Penguin.

Goodman, R., and Jinks, D. 2008. Incomplete Internalization and Compliance with Human Rights Law. European Journal of International Law 19 (4): 725–748. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chn039.

Gowan, R., and Witney, N. 2014. Why Europe Must Stop Outsourcing its Security. European Council on Foreign Relations, December 15. URL: https://ecfr.eu/publication/why_europe_must_stop_outsourcing_its_security326/.

Gueldry, M., Gokcek, G., and Hebron, L. (eds.) 2019. Understanding New Security Threats. London: Routledge.

Gurr, T. 1993. Minorities at Risk: A Global View of Ethnopolitical Conflicts. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

Hale, T. 2018, November. The Role of Sub-state and Nonstate Actors in International Climate Processes. Environment and Resources Department. Chatham House: 1–16. URL: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2018-11-28-non-state-sctors-c....

Hassner, P. 1995. Violence and Peace: From the Atomic Bomb to Ethnic Cleansing. Budapest: Central European University Press.

Hazony, Y. 2018. How Americans Lost Their National Identity. Time, October 23. URL: https://time.com/5431089/trump-white-nationalism-bible/.

Holsinger, B. 2007. Neomedievalism, Neoconservatism and the War on Terror. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Holsti, K. J. 2006. The Decline of Interstate War: Pondering Systemic Explanations. In Väyrynen, R. (ed.) The Waning of Major War: Theories and Debates (pp. 43–64). New York: Routledge.

Human Security Report. 2005. Human Security Report Project (HSRP). URL: http://www.humansecurityreport.info/.

Kacowicz, A. M. 1999 Regionalization, Globalization, and Nationalism: Convergent, Divergent, or Overlapping? Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 24 (4): 527–555. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40644977.

Kaldor, M. 1999. New and Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Kelly, R. E. 2007. Security Theory in the ‘New Regionalism’. International Studies Review 9 (2): 197–229. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4621805.

Kelman, H. C. 2001. The Role of National Identity in Conflict Resolution. In Ashmore, R. D., Jussim, L., and Wilder, D. (eds.), Social Identity, Intergroup Conflict, and Conflict Resolution (pp. 187–212). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Khanna, P. 2009. The Next Big Thing: Neomedievalism. Foreign Policy, September 17. URL: https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/09/17/the-next-big-thing-neomedievalism/.

Kingsbury, D. 2017. Passion and Pain: Why Secessionist Movements Rarely Succeed. The Conversation, October 17. URL: https://theconversation.com/passion-and-pain-why-secessionist-movements-rarely-succeed-85097.

Klauck, C. 2014. New Medievalism in Lebanon: The Case of Hezbollah. Politicus Journal 4 (1): 63–76.

Kobrin, S. 1998. Back to the Future: Neomedievalism and the Postmodern Digital World Economy. Journal of International Affairs 51 (2): 361–386. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24357500.

Kopyciok, S., and Silver, H. 2021. Left-Wing Xenophobia in Europe. Frontiers in Sociology, June 10 (6): 1–17. URL: https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.666717.

Korostelina, K. 2004. The Impact of National Identity on Conflict Behavior: Comparative Analysis of Two Ethnic Minorities in Crimea. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 45 (3–4): 213–230. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715204049594.

Krasner, S. D. 1988. Sovereignty: An Institutional Perspective. Comparative Political Studies 21 (1): 66–94. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414088021001004.

Krastev, I., and Holmes, S. 2019, October 24. How Liberalism Became ‘the God that Failed’ in Eastern Europe. The Guardian. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/24/western-liberalism-failed-post-communist-eastern-europ....

Lele, A. 2014. Asymmetric Warfare: A State vs Non-State Conflict. Oasis 20: 97–111.

Levy, J. 1983. War in the Modern Great Power System. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press.

Mack, A. 1975. Why Big Nations Lose Small Wars: The Politics of Asymmetric Conflict. World Politics 27 (2): 175–200. URL: https://doi.org/10.2307/2009880.

Norell, M. 2003. A New Medievalism? – The Case of Sri Lanka. Civil Wars 6 (2): 121–137. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/13698240308402536.

Norval, A. J. 1999. Rethinking Ethnicity: Identification, Hybridity and Democracy. In Yeros, P. (ed.), Ethnicity and Nationalism in Africa: Constructivist Reflections and Contemporary Politics (pp. 61–88). London: Macmillan.

OECD. 2022. Trust in Government (indicator). URL: https://doi.org/10.1787/1de9675e-en.

Ortiz-Ospina, E., and Roser, M. 2016. Trust. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. URL: https://ourworldindata.org/trust.

Pałka, W. 2020. The Awakening of Private Military Companies. The Warsaw Institute, August 20: 1–15. URL: https://warsawinstitute.org/awakening-private-military-companies/.

Peyton, B., Bajjalieh, J., Shalmon, D., Martin, M., and Bonaguro. J. 2021. Cline Center Coup D’état Project Dataset Codebook. Cline Center Coup D’état Project Dataset. Cline Center for Advanced Social Research, January 8. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. URL: https://doi.org/10.13012/B2IDB-9651987_V2.

Polyakova, A. Taussig, T., Reinhert, T., Kirişçi, K., Sloat, A., Kirchick, J., Hooper, M., Eisen, N., and Kenealy, A. 2019. The Anatomy of Illiberal States: Assessing and Responding to Democratic Decline in Turkey and Central Europe. Foreign Policy at Brookings, February: 1–55. URL: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/illiberal-states-web.pdf.

Ralph, J. 2017. The Responsibility to Protect and the Rise of China: Lessons from Australia’s Role as a ‘Pragmatic’ Norm Entrepreneur. International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 17 (1): 35–65. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/irasia/lcw002.

Redfield, P. 2005. Doctors, Borders, and Life in Crisis. Cultural Anthropology 20 (3): 328–361. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3651595.

Reid-Henry, S., and Sending, O. J. 2014. The ‘Humanitarianization’ of Urban Violence. Environment and Urbanization 26 (2): 427–442. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247814544616.

Risse, T., and Sikkink, K. 1999. The Socialization of International Human Rights Norms into Domestic Practices: Introduction. In Risse, T., Ropp, S. C., and Sikkink, K. (eds.), The Power of Human Rights: International Norms and Domestic Change (pp. 1–38). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rubinoff, A. G. 2000. The Multilateral Implications of Ethno-Nationalist Violence in South Asia. South Asian Survey 7 (2): 273–293. URL: https:// doi.org/10.1177/097152310000700209.

Sambanis, N., and Schulhofer-Wohl, J. 2019. Sovereignty Rupture as a Central Concept in Quantitative Measures of Civil War. Journal of Conflict Resolution 63 (6):1542–1578. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002719842657.

Sarkees, M. R., Wayman, F. W., and David Singer, J. 2003. Inter-State, Intra-State, and Extra-State Wars: A Comprehensive Look at Their Distribution over Time, 1816–1997. International Studies Quarterly 47 (1): 49–70. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3096076.

Silliman, G. S., and Noble, L. G. 1998. Citizen movements and Philippine democracy. In Silliman, G. S., and Noble, L. G. (eds.) Organizing for De-mocracy: NGOs, Civil Society, and the Philippine State (pp. 280–310). Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press.

Silver, L., Fagan, M., Connaughton, A., and Mordecai, M. 2021. Views about National Identity Becoming More Inclusive in U.S., Western Europe. Pew Research Center, May 5: 1–54. URL: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2021/05/05/views-about-national-identity-becoming-more-inclusive-....

Simms, B. 2003. The End of the ‘Official Doctrine’: The New Consensus on Britain and Bosnia. Civil Wars 6 (2): 53–69. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/13698240308402533.

Slaughter, A. M. 1997. The Real New World Order. Foreign Affairs, 76 (5): 183–197. https://doi.org/10.2307/20048208.

Takahashi, M. (ed.) 2019. The Influence of Sub-state Actors on National Security: Using Military Bases to Forge Autonomy. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Talentino, A. K. 2005. Military Intervention after the Cold War: The Evolution of Theory and Practice. Ohio: Ohio University Press.

Tetrais, B. 2012. The Demise of Ares: The End of War as We Know It? The Washington Quarterly 35 (3): 7–22.

Ünay, S. 2017. Neo-Medievalism and the New Regional Order in the Middle East. The Daily Sabah, October 7. URL: https://www.dailysabah.com/columns/sadik_unay/2017/10/07/neo-medievalism-and-the-new-regional-order-....

UNDP. 2016. Engaged Societies, Responsive States: The Social Contract in Situations of Conflict and Fragility: Concept Note. The Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre (NOREF): 1–36. URL: https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/Democratic%20Governance/Social_Contract_in_Situations_....

van Veen, E. 2007. The Valuable Tool of Sovereignty: Its Use in Situations of Competition and Interdependence. Bruges Political Research Paper, College of Europe, no. 3, May. URL: https://aei.pitt.edu/10872/1/wp3%20VanVeen.pdf.

Winn, N. 2019. Between Soft Power, Neo-Westphalianism and Transnationalism: The European Union, (Trans)National Interests and the Politics of Strategy. International Politics 56: 272–287. URL: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-017-0126-9.

Woods, E. T., Schertzer, R., and Kaufmann, E. 2011. Ethnonational Conflict and its Management. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 49 (2): 153–161. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2011.564469.

Zielonka, J. 2014. Is the EU Doomed? (Global Futures).

Cambridge: Polity Press.