Struggle to Balance National Interests: China's High-Speed Rail Diplomacy in Southeast Asia

Journal: Journal of Globalization Studies. Volume 16, Number 1 / May 2025

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/jogs/2025.01.05

Wenjie Huang, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Since China proposed the going-out strategy of HSRs in 2009, China's HSR diplomacy has sparked heated debates about China's intentions. Fr om an economic diplomacy perspective, this article attempts to understand China's HSR diplomacy in SEA fr om four dimensions: context, process, theatre, and outcomes. Available second-hand data show that China's HSR diplomacy, with a consistent tendency as China's overall economic diplomacy over the past 70 years, tends to be more economic than political. In SEA, however, China's growing economic influence has been accompanied by a declining regional reputation. China's increasingly pragmatic approach to protecting its overseas economic interests without making sufficient efforts to handle local opposition mainly caused by environmental and social factors, has led to local Sinophobic sentiments. The conflict represents a microcosm of China's overseas railway projects under the BRI, where the country is attempting to balance the pursuit of economic benefits with the maintenance of a positive global image.

Keywords: high-speed railway, economic diplomacy, Southeast Asia, China’s intention, national interests.

Introduction

Since the official launch of high-speed railway (HSR) development strategy in 2009, China's HSR has continued to achieve leapfrog development. China is expected to dominate the global HSR investment market between 2014 and 2030, attracting increasing international attention (Barrett 2014; Chan 2017). By 2022, China's overseas HSR network had exceeded 40,000 kilometers, ranking first in the world in terms of length (Luo 2022). China's overseas HSR strategy widely encompasses three orientations including Eurasia, Central Asia, and Trans-Asia, among which, in Southeast Asia (SEA), China has actively pursued competitive tendering processes for railway projects covering almost all ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) countries, whose projects form significant parts of China's extensive pan-Asian railway network. According to the development goal in the Mid-to-Long-Term Railway Development Plan to create internationally competitive Chinese HSR brands, there is a further tendency for China's HSRs to continue to be international (Barrett 2014).

Large-scale infrastructure, like railways, can be used as a primary foreign policy tool to achieve commercial interests or expand global influence. Okano-Heijmans (2011: 17) defines ‘economic diplomacy’ as ‘the use of political means as leverage in international negotiations, to enhance national economic prosperity, and the use of economic leverage to increase the political stability of the nation.’ Based on her definition, China's HSR can be comprehended as a government instrument to achieve economic and political effects. On the one hand, as an advanced engineering technology owned by only a few countries, HSR projects that are technology-intensive and monopolistic can boost a country's transition to high-value-added exports (Oh 2018; Leverett and Wu 2017; Ker 2017), provide opportunities to export domestic industrial overcapacity, and enhance Beijing's global image as a leader in high-value-added manufacturing (Zhang and Sun 2016; Ker 2017; Obe and Kishimito 2019; Zhao 2014). On the other hand, as a state-led initiative motivated by a combination of foreign policy and domestic economic objectives (Ker 2017) and intertwined with Beijing's key foreign policy initiatives, typically the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the internationalization of China's HSR has raised broad political concern and sparked heated debate about motivations and implications of the strategy (Pavlićević and Kratz 2017). Contrary to some views that the HSR outreach strategy is likely to promote mutual trust, respect, and benefit, and strengthen cooperation on security with neighboring countries (Xu 2018), many of the existing perceptions fit neatly into the premise of the China threat narrative, which understands the projects in a negative, alarming, and threatening way (Pavlićević and Kratz 2017; Pan 2012). Viewed as a ‘political train’ for China's ambitious connectivity to neighboring countries, the massive railway projects have been given symbolic political significance, including persuading host countries to accept China's increasing influence (Martin 2016) or shaping a more favorable environment for China's rejuvenation (Yan 2014). There is also a widespread suspicion that the HSR lines, which provide unimpeded channels to host countries, could be used for military purposes like transporting military equipment and personnel (Kratz and Pavlićević 2017).

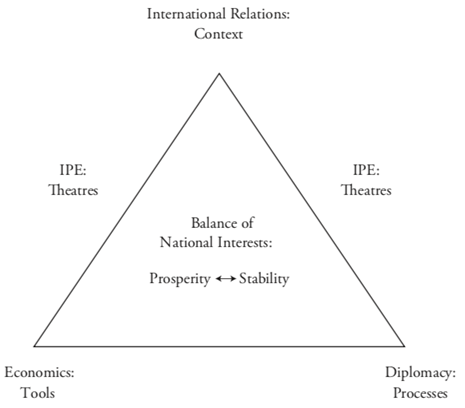

Interested in exploring the potential intention and effect of China's transnational HSR expansion, this article departs fr om extant scholarship's predominant focus on recipient-state perspectives, and attempts to comprehend China's HSR strategy in SEA from Beijing's standpoint, based on a comparison with similar projects in other regions. The analysis was based on an economic diplomacy framework by Okano-Heijmans (2011), which consists of four basic dimensions –context, tools, process, theatre, and outcomes (see Figure 1), as well as a variety of second-hand sources, including existing literature, news, trade data from WITs, and project data from Aiddata. The findings imply that in comparison to similar projects in other regions, such as the China-Europe trains, the railway projects in SEA are subject to greater political controversy, but these projects actually take on a more pragmatic trend prioritizing economic interest over political influence. However, this does not mean that China's HSR diplomacy has a purely economic purpose. Instead, in the face of continuing territorial disputes in the South China Sea and threats from hostile foreign powers to curb China's regional influence, HSR projects are used as an economic tool to enhance China's soft power in the SEA for national security. Unfortunately, current findings indicate Beijing's failure to use HSR to achieve higher levels of soft power while increasing economic prosperity and political influence, which hinders the long-term sustainability of China's pan-Asian railway network.

The following parts of the article will first briefly review the historical development of China's economic diplomacy to understand the context of Beijing's promotion of the transnational expansion of HSRs, and then outline the progress of the projects thus far, as well as the challenges faced. The third section will analyze the business side of China's HSR diplomacy, followed by an analysis of the potential impact of the projects on China's political standing in SEA, and the final section will provide a conclusion and discussion.

Fig. 1. Analytical framework

Source: Okano-Heijmans 2011: 21.

Context: The Trajectory of China's Economic Diplomacy over the Past 70 Years

The emergence of economic diplomacy can be traced back to ancient times when economic interests were already seen as a driver of diplomatic relations, although the influence of economic factors was then considered as secondary to political considerations (van Bergeijk, Okano-Heijmans, and Melissen 2011). However, with the increasing instability and uncertainty of global institutions and the rapid changes in the shifting balance of power under globalization, more and more countries are paying increasing attention to the potential impact of economic activities in international affairs. Against this background, a number of concepts such as ‘commercial diplomacy,’ ‘trade diplomacy,’ ‘financial diplomacy,’ and ‘economic statecraft’ have been explored, which are primarily concerned with the means, process and practice of a policy. Among them, ‘economic diplomacy’ consists of combined dimensions of economic activities, politics, diplomacy, and their interaction. It aims to achieve national goals using instruments in a non-coercive manner, with the state playing a primary role (Okano-Heijmans 2011).

So far, China's economic diplomacy includes the use of trade, investment, and financial policies to support its diplomatic, political, and strategic purposes, explicitly focusing on securing resources, expanding export markets, and promoting China's soft power (Chaziza 2019). Looking back at the development of China's economic diplomacy over the past 70 years, it can be divided into four stages: the disassociation period, the return period, the integration period, and the leadership period (see Table 1). Along with the shift in China's role from a significant aid recipient country to a donor country after independence, there is a tendency for China's economic diplomacy objectives to change from more political-oriented to more economic-oriented. This trajectory of development reveals the influence of both the international and domestic context on the status of Chinese economic diplomacy and also the return and deepening of China's involvement in global affairs.

Table 1

China's economic diplomacy over the past 70 years

Period | Year | Political | Status | Partners | Approaches | Objectives |

Disassoci- period | 1949–1978 | International: Cold War; the opposition of political systems

Domestic: Planned economy | A relatively weak status in China's overall diplomatic framework; confrontational and revolutionary | Socialist countries such as the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe | Preferential loans Technical assistance Barter trade Promotion of diplomacy through aid, e.g. in 1950, China provided material aid to Vietnam and North Korea | Emerged from isolation status Anti-imperialism and anti-hegemony |

Return period | 1978–2000 | International: the end of the Cold War; the trend of multipolarization

Domestic: reform and opening up; the three–step development strategy; | The status that enhan-ced and served China's domestic strategy | New partner countries represented by Japan, Germany and Africa | Subsidized loans Aid project cooperation A grand aid strategy that combined aid with investment Accepted aid from countries like Japan and Germany Provided assistance to developing countries | Return to the international stage; Creation of |

Integration period | 2001–2008 | International: join the WTO; the strategy of ‘keep a low profile and make a difference’; Western dominated international political and economic order | Proactivity and aggressiveness; became official expression in 2004 White Paper on Diplomacy | The scope of recipient countries was expanded | Foreign aid Bilateral trade agreement and other agreements like the FTA Regional trade cooperation | Integration into globalization and regional integration |

Leading period | 2008–present | The financial crisis; One Belt and One Road; Progress of RMB Internationalization | Became more and more important in China's foreign policy | Major countries in the world | Financial diplomacy Infrastructure construction One Belt and One Road Initiative Multilateral financial institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the New Development Bank | Protection |

Source: author's compilation based on He 2019.

Before its reform and opening up, China was marginalized and behaved as an outsider to the world system. Thus, foreign aid to socialist countries like Vietnam was used as a primary instrument to help China emerge from its isolation and fight imperialism and hegemony, even though it faced persistent impoverishment and structural fragility at home. Later, after the turn of the twenty-first century, more tactics than loans or technical assistance (TA) were used to interact with a wider range of states to generate potential cooperation. Before 2008, China's economic diplomacy focused on how to serve the development of the domestic economy and promote integration into globalization and regional development. A milestone event was China's decision to join the WTO with an advocated concept of ‘broad consultation, joint contribution and shared benefits’ of global governance. After China's return to the international stage, the international environment has long been dominated by norms centered on Western values, in which Chinese companies are at a relative disadvantage. To create a more favorable international environment, China has tried to increase its influence and voice by setting its own leading norms like the principle of ‘non-interference’ and the ‘Beijing Consensus,’ which has become even more popular in parts of Asia, Africa, and Latin America than the previously dominant ‘Washington Consensus’ (Nye and Wang 2009).

After the 2008 financial crisis, when China became the world's second largest economy, the protection of overseas economic interests became Beijing's major concern. Infrastructure construction with supporting development banks or funds has become essential to China's latest approaches to economic diplomacy. Well-known multilateral financial institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the BRICS Development Bank (BDB), the Silk Road Funds, and other multilateral financial institutions have indicated that China is seeking to increase its global influence. Just within the past few decades, infrastructure diplomacy has become the core part of China's foreign policy, in which HSR exports play a vital role (Chan 2016).

Process: China's tortuous HSR bids in SEA

China's HSR diplomacy refers to railway cooperation between countries, which is mainly carried out through inter-governmental negotiations and agreements (Hu, Liu, and Kwak 2017; Huang, Ge, Ma, and Liu 2017). With the implementation of the HSR going out strategy, China has been an active bidder for HSR projects all over the world, among which, China's pan-Asian high-speed rail network in SEA stands out for its extensive connectivity, greater government sensitivity and China's growing economic influence. Compared to other flagship railway projects under the BRI, such as the Iranian High-speed Railway, the Two Oceans Railway, and the African Railway, which are not directly connected to inland cities in China, the 3,000 km network starting from Yunnan in Southwest China links nearly all the key countries in ASEAN, with the three lines running through Vientiane in Laos, Yangon in Myanmar, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam, Bangkok in Thailand, Phnom Penh in Cambodia, Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia, to Singapore. By the end of 2023, Beijing had negotiated railway construction with at least nine ASEAN countries, demonstrating China's ambition to complete the transcontinental network.

Nonetheless, the unstable political context in the host countries has hindered the negotiation process. For the Sino-Thai HSR project, the whole process went from the Abhisit government (2008–2011) to the subsequent negotiations with the Yingluck government (2011–2014) and later Prayut government (2014–2023), with each regime change requiring a new round of negotiations (Jiang 2022). Similarly, in November 2016 and May 2017, China Communications Construction Group (CCCC) and Malaysian Rail Link signed separate agreements for the Malaysia East Coast Rail Link, comprising Phases I and II, with a total value of RMB106 billion. A groundbreaking ceremony was held in August 2017, with an estimated completion date of 2024. However, when Mahathir came to power in 2018, the East Coast Rail Link and HSR line from Kuala Lumpur to Singapore were temporarily shelved as one of the highlights of anti-corruption purges against the previous government (Ibid.). In response, China threatened to prosecute Malaysia for breaching a previously signed agreement to restart the East Coast Rail Link in 2021 after new rounds of negotiations. Still, there was no progress in constructing the Malaysia-Singapore line, a necessary part of China's Pan-Asian rail network, which was canceled. As shown in Table 2, among all the railway projects listed, only one was completed, while more than half of the projects were suspended/canceled or suspended before construction resumed. Even for the projects that were under construction, the negotiation process tended to be long and back-and-forth, reflecting the host countries' fluctuating support of the Chinese partnership.

Table 2

China’s railway bids of the Pan-Asian railway network in SEA

Country | HSR Project | Length/km | Cost (US $ billion) | Progress |

Indonesia | Jakarta–Bandung high-speed railway | 143 | 7.85 | Bid: 2008 |

Vietnam | North-south high-speed railway (Hanoi-Ho Chi Minh City) | 1545 | 58.7 | Bid: 2010, failed |

Laos | Laos-China railway | 427 | 6.04 | MoU: 2010 |

Thailand | Sino-Thailand high-speed railway (Nong Khai–Bangkok) | Phase1: 252 | 10 | MoU: 2014 |

Malaysia | East Coast Rail Link | 648 | 10.7 | Agreement: 2016 |

Singapore & Malaysia | Kuala Lumpur–Singapore high-speed railway | 350 | 26 | Bid: 2017 |

Myanmar | China-Burma high-speed rail (Kunming-Rangoon) | 1920 | 20 | Contract: 2011 |

Philippines | Bicol rail scheme | 565 | 2.8 | Current status: Current status: negotiation |

Cambodia | Kunming-Cambodia high-speed railway | n.a. | n.a. | Current status: planned |

Source: author's compilation based on online sources.

Compared to the China-Europe freight train, which was initiated by local actors as a low-cost means of transport (Tjia 2020), the Pan-Asian rail network is a state initiative and therefore more politically contentious, especially for cooperation with smaller SEA countries, including those with which China is in conflict over the South China Sea. It is evident from Table 2 that China faces more challenges in promoting HSR diplomacy in countries with unfavorable diplomatic relations. For instance, in the 2006 bidding process for the North-South HSR, despite the Vietnamese government's request for China's assistance in sending experts to study the project, they ultimately chose Japan as their cooperation partner, a decision that was met with disappointment in China (Xing 2023). Besides, the China-Burma railway was shelved for more than a decade after the 2011 MoU, which scheduled the project to be initiated within three years and be completed in five and a half years. Myanmar's Ministry of Railways and Transport stated that the project would not be implemented, citing the expiration of the MoU and the absence of a renewal request from the Chinese side (Jiang 2022).

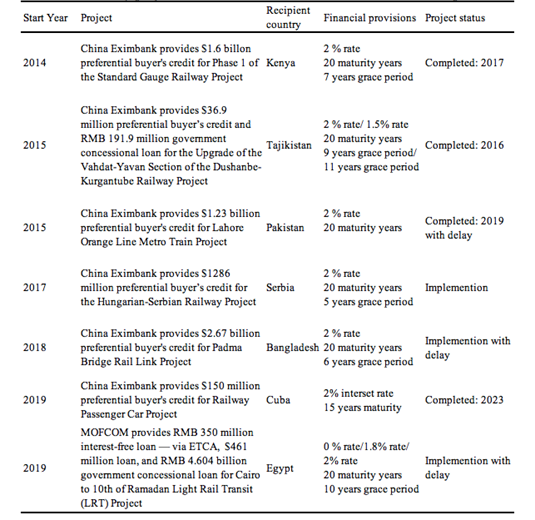

In addition, high debt levels and rising loan rates pose financial risks that could lead to project delays. Chinese projects under the BRI are strongly backed by state-owned policy banks, including the Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China, as well as sovereign wealth funds (e.g., the Silk Road Fund), which provide a range of financial instruments, typically grants and low- or zero-interest concessional loans, to support the development of recipient countries (Sejko 2016). A significant proportion of the funding, up to 85 per cent, has been provided by China to railway projects like those in Pakistan under the CPEC and the Hungarian-Serbian railway. Notably, despite the geopolitical importance of the SEA, China has not granted more preferential terms to related railway projects than to other counterparts (see Table 3). Specifically, while China rejected Thailand's request to lower the loan rate for Sino-Thai HSR (Chen 2016), it granted a significant concession on loans to Bangladesh, as low as 2 %, and also allowed Pakistan to successfully lower the interest rate on infrastructure projects worth about $11 billion from 3 % to 1.6 % through lobbing (Wikipedia n.d.).

Table 3

Chinese railway projects in non-ASEAN countries with a loan rate of up to 2 %

Source: Aiddata.

While negotiating on the Jakarta–Bandung HSR in Indonesia, China's first flagship HSR project in SEA, China offered to bear most of the cost, with CDB providing 75 per cent of the total financing on generous terms without requiring a sovereign loan guarantee from the local government. The interest rate on the total guarantee-free loans was as low as 2 % (Leverett and Wu 2017; Qin 2021), which outcompeted Japan that requested the Indonesian government to fund in bidding (Drache, Kingsmith, and Qi 2019). Moreover, China did not dominate the joint venture through high investment but left a larger share (60 %) to the Indonesian companies – China Railway Corporation (CRC) reportedly took over only 40 % of the joint venture.

However, this generosity gradually faded after the Jakarta-Bandung HSR project. For instance, in the construction of the subsequent Boten-Vientiane railway, even China Exim Bank announced to undertake US$480 million (70 % out of the total cost) in annual instalments over the medium term to the Sino-Laos joint venture company, the interest rate was 0.3 % higher than Indonesia's, and China held 70 % of the joint venture's shares. Before the groundbreaking in 2017, the Sino-Thai HSR experienced a five-year negotiation process without reaching a final consensus on the financial terms. Thailand was dissatisfied with the disparity in interest rates, with China demanding a 2.5 % interest rate for Thailand but only 2 % for Indonesia. The conflict over the loan interest rate led to the Sino-Thai railway being postponed three times before construction (Fu 2016). Finally, the Thai government had to finance the rail line itself (Pavlićević and Kratz 2017). When it comes to the recent railway bid in the Philippines, it was reported that China asked for a 3 per cent interest rate on loans sought by the Philippines to build three railway projects – two in Luzon, one in Mindanao – estimated to cost at least P276 billion. The former finance secretary Carlos Dominguez warned that China would demand higher interest rates than those offered by alternative financiers like Japan (as low as 0.1 %). Thus, Dominguez decided to directly cancel the application instead of suspending it (Rosales 2022).

Theatre: Why SEA? A Business PerspectiveA number of studies have identified the economic impacts of HSR on along-route cities, including but not limited to increased productivity, reduced delivery costs and transit times of goods, increased consumption, and technological innovation under certain conditions (Kobayashi and Okumura 1997; Priemus 2009; Couto 2011; Chu, Wang, and Chen 2011; Zhao 2014). The economic benefits brought by the HSR projects, such as ‘spatial development,’ are evidenced to facilitate trade, new urban centers, and real estate development along the lines (Martin 2016). These benefits are expected to spill over from the cities along the rail lines to the surrounding areas, thus boosting the regional economy (Zhao and Zhang 2012).

Over the past decade, China has remained the largest trading partner in goods with ASEAN, and its share among all extra-ASEAN trading partners is steadily increasing year by year, reaching a quarter in 2020 (see Table 4). Over the past two decades, China's total exports to ASEAN have doubled more than 15-fold, reaching about US$289.9 billion (30 % of ASEAN's total imports) in 2020. Among major destinations, China's exports to Vietnam grew by 53 %, followed by Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia (Nugroho 2015; WITs Data n.d.). Also, China's imports from ASEAN also increased significantly. In 2000, China's imports from ASEAN were only US$16.4 billion, 3.8 % of ASEAN's total exports. However, in 2021, the volume reached US$280.8 billion, with China's share rising to 21 % (The ASEAN Secretariat 2022). Overall, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Indonesia are China's most important ASEAN trading partners in terms of value, with Vietnam showing huge potential for growth.

Table 4

China's rank and share in trade in goods with ASEAN, 2009–2021

Value | Share | Rank | |

2009 | 178,049 | 15 | 1 |

2010 | 234,296 | 16 | 1 |

2011 | 294,989 | 16 | 1 |

2012 | 319,390 | 17 | 1 |

2013 | 351,583 | 18 | 1 |

2014 | 366,711 | 19 | 1 |

2015 | 363,497 | 21 | 1 |

2016 | 368,567 | 21 | 1 |

2017 | 440,973 | 22 | 1 |

2018 | 478,535 | 22 | 1 |

2019 | 507,963 | 23 | 1 |

2020 | 503,302 | 25 | 1 |

2021 | 669,200 | 25 | 1 |

Source: ASEAN Secretariat 2022.

In particular, Yunnan, which borders Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam, has become an important hub city in the Pan-Asian rail network, connecting the SEA countries with the inland areas of southwest China. In the early 2000s, trade between Yunnan and ASEAN countries surged by 26 % year-on-year, and the trade value in 2004 (US$1.28 billion) accounted for 34.1 % of the province's total foreign trade, with Myanmar and Vietnam coming first and second among the top ten trading partners (HKTDC 2005). Meanwhile, the Yunnan government has attracted famous Chinese and foreign logistics companies (e.g., China's Shunfeng Express and Singapore's MapletreeLog) to settle and set up overseas logistics companies widely in Laos, Thailand, Myanmar, Vietnam, and other countries to establish a cross-regional logistics network connecting China and the SEA. The Yunnan provincial economic work conference held in 2021 indicated that the logistics driven by corridors was only the first step. The Yunnan government emphasized that trade with logistics should be further promoted and that industries should be developed on a larger scale via trade (Department of Commerce of Yunnan Province 2022). Yunnan's economic weaknesses in a geographical location far away from China's three economic cores (the Yangtze River Delta, the Pearl River Delta, and the peripheral sea region) are expected to be turned into an advantage by importing various goods and vibrant natural resources from Indo-China Peninsula to China's hinterland (Zhao 2014). So far, shuttle trains launched by China have demonstrated the economic potential of China's cross-border railways to generate economic returns. For instance, the expansion of China-Europe freight trains has outpaced the growth of global trade – a total of 8,641 China-Europe freight trains ran in the first six months of 2023, up 16 % year-on-year, carrying about 936,000 standard containers of goods, an increase of 30 % during the same period last year (Global Times 2023). Similarly, from January to February 2023, the cross-border goods on the Laos-China railway reached 600,000 tons, of which 510,000 tons were imports, which presented a fivefold increase year on year. The total value of international freight transport exceeds 600 million RMB in six months, with goods from seven provinces, including Hebei, Shandong, and Jiangsu, being transported to Laos, and further to Myanmar, Thailand, and Singapore by train (Guo and Huang 2023).

Besides, China has manifested a ‘resource for technology’ approach to HSR cooperation with some underdeveloped countries. One example of this is the construction of the China-Laos railway, for which the loan was supported by revenues from five potash mines in Laos. Furthermore, the government granted extensive concessions to Chinese investors for a wide range of business opportunities, including rubber plantations, banana estates, and casino operations (Leverett and Wu 2017; Reuters 2021). ‘China builds high-speed railways for other countries when it has funds, or it takes something else for change if the recipient country does not have enough money, which is a fair way of trading,’ said a relevant person in charge from the Ministry of Railways in an interview with the Southern Weekend (Han 2014). While China provides construction funds, technology, and equipment for the HSR projects and allows the host countries to participate in the operation, it negotiates for a local resource in exchange for the HSR construction fees, such as oil and gas resources in Central Asia and potash mines in Myanmar, thus establishing a long-term cooperation mechanism.

For the host countries, HSR, as a core component of China's overseas investment under the BRI, provides opportunities to create new jobs, increase foreign currency income, train workers, and generate spill-over effects for local development (Bräutigam and Tang 2011). However, as recipient countries' exports to China are growing much more slowly than their imports, the deepened cooperation has further widened the trade deficit. This has led many critics to question whether China's OBOR is a ‘win-win cooperation’ that will benefit all stakeholders (Scobell 2018). Indeed, a considerable number of China's overseas railway projects have met with resistance from local communities. For example, in Africa, the construction of the Standard Gauge Railway project in Kenya was met with local resistance and sparked considerable controversy. The public outcry arose from concerns about Beijing's potential acquisition of strategic assets such as the port of Mombasa. In South Asia, popular protests suspended the marking of demolition sites around heritage sites for the construction of the Lahore Orange Line metro train in Pakistan (Aiddata n.d.). These bottom-up problems demonstrate the need for China to pay greater attention to the influence of soft power beyond the purely economic factor in order to reduce the China threat narrative and to improve its reputation.

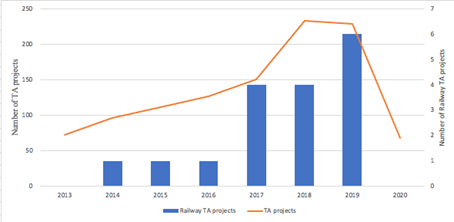

Outcome: Unbalanced National Interests Threaten Long-Term SustainabilityFor decades, the world has witnessed Beijing spending billions of dollars to increase its influence and improve its global perception. Since 2013, according to Aiddata, there has been a notable increase in the number of Chinese investments in TA projects, mainly in the provision of scholarships and training (see Figure 2). Excluding medical humanitarian aid projects related to COVID-19, there was also a particular increase in TA projects related to railways from 2016 to 2019. These projects, seven located in SEA countries and five in African countries, focused on providing training programs related to railway technology, engineering, and operations. The upward trend shows that Beijing is committed to enhancing the country's soft power and fostering a positive image of a responsible international power.

Fig. 2. Chinese TA projects from 2013 to 2019

Source: Aiddata, 2024.

Soft power, as interpreted and developed by scholars like Nye, is the ability to get what one wants through attraction rather than coercion or payment. As a form of national power, strongly correlated with a country's endowment of resources based on culture, values, and policies, it is similar to, but not the same as, influence at the be-havioral level (Nye 2008). This approach encompasses a range of strategies, including but not limited to the establishment of organizations or agendas, the planning of overseas infrastructure projects, the promotion of people-to-people exchanges, and so on. In order not to frighten its neighbors, the use of soft power fits into China's foreign policy strategy and is vital for generating positive long-term influence like nation-building and branding. However, despite China's growing investment in TA projects, its soft power has conversely deteriorated, with China facing increasing criticism in regions like Africa and also SEA, wh ere China has been one of the leading investors (Shanbaugh 2015).

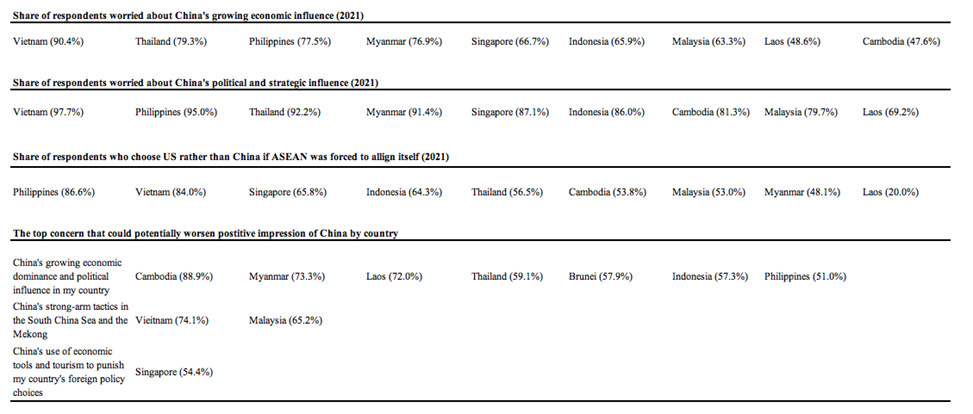

According to the 2021 report by the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, although 76.3% of respondents viewed China as the most influential power in the SEA, 72.3% of them had negative sentiments, indicating that China may still have a long way to go to win the hearts and minds of the ASEAN people. In terms of the underlying causes of negative sentiment, with the exception of Vietnam and Malaysia, wh ere respondents indicated that concerns about China's use of strong-arm tactics in the South China Sea and the Mekong River were a significant factor in their negative perceptions of China, concerns about China's growing economic dominance and political influence were the most frequently cited concerns. In Cambodia, for exampe, 88.9 % of respondents said that the issue had a detrimental impact on their positive perception of China (see Figure 3). ‘It is crucial for the state to have a strategy to create a balance between investments from different countries and not to depend on or be biased towards just one particular country like China,’ said a former board member of the Bank of Thailand. In this context, the construction of the Pan-Asian railway network is highly likely to trigger stronger Sinophobic sentiments while increasing China's regional economic influence, leading to more challenges that may hinder China's promotion of HSR in SEA.

In addition to the project delays caused by the political and project financial factors previously outlined in section three, other factors, particularly environmental and social factors, may contribute to a further decline in China's reputation at the grassroots level. For example, the construction of the Jakarta–Bandung HSR has been met with local protests over potential damage to land and homes, and environmental concerns over waste dumping, which led to the project's completion date being postponed from 2019 to 2023 (South China Morning Post 2016; 2017; Garlick 2017; Barahamin 2022). In Myanmar, despite Beijing's statement that land exploitation along the railway would enhance the commercial feasibility of the project and promises of additional funding, opposition came from local individuals, political parties, and social organizations, and led the Myanmar government to cancel the HSR project throughout the country and put the plan on hold indefinitely (Wang and Jia 2017; Martin 2016; Jiang 2022).

Fig. 3. Poll on Southeast Asian public perceptions of China

Source: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute 2021.

To alleviate local resistance caused by potential debt ratios, land damage, and Sinopobic sentiments, China has made concessions in many respects, including withdrawing ownership of land around the line and resource collateral for its loans, as China did in the Sino-Thai HSR negotiations, wh ere land use remained with Thailand and a rice-for-rail agreement was proposed (Kratz and Pavlićević 2017). At the national level, Chinese government support focused on improving core HSR R&D and maintaining a low-cost and high-speed construction advantage (Chan 2016; Nolan 2014; Naughton 2015) was also effective in international competition. However, China's flexibility in financing, ownership, and implementation of these proposed railway projects did not relieve anxieties and worries. As many Chinese scholars have pointed out, more attention should be paid to the importance of letting ‘politics and culture go first’ in promoting China's BRI. Moreover, in the long run, the core issue that will help China gain more local support still lies in how China can promote inclusive cooperation, taking into account more environmental, social, and governance issues, as supported by its win-win cooperation.

Conclusion and DiscussionDeveloped against the backdrop of China's global rise, China's HSR diplomacy has caused broad discussion on China's intentions in promoting HSR abroad. Opinions are divided on whether the purpose of the strategy is more political or economic (Oh 2018; Leverett and Wu 2017; Ker 2017; Pavlićević and Kratz 2017). A review of the development of China's economic diplomacy over the past 70 years, suggests that China's HSR going out has occurred n the context of China's commitment to using economic diplomacy to protect its economic interests abroad (He 2019). However, different to pure ‘power-play’ economic diplomacy, which seeks to increase international influence through intervention, or those of ‘business-end’, which use diplomatic instruments to promote economic development (Van Bergeijk et al. 2011; Okano-Heijmans 2011), China's HSR diplomacy is expected to be a strategic dual-ended strategy to achieve both economic prosperity and national security by increasing China's soft power. By focusing on the progress and challenges of HSR projects in SEA, the article finds that: first, compared to other regions, China's railway projects in SEA are more politically controversial and face greater challenges in project implementation; second, contrary to China Threat Theory, China's approach to related railway projects shows a more pragmatic and economically oriented disposition; third, China's railway projects in SEA exemplify the challenge of balancing national interests – a conflict between China's economic influence and regional reputation, faced by the country's overseas infrastructure. Such an unbalance of national interests stems from fears of over-dependence on China. Besides, other well-documented issues such as high debt, social and environmental concerns have caused local protests and pose additional challenges to the long-term sustainability of China's HSR diplomacy.

Notably, even as the largest developing economy, China's HSR cooperation with smaller counterparts in SEA is not characterized by its unilateral dominance. Factors such as each party's impatience, the host country's external options, and domestic constraints can affect the outcomes of project negotiations (Leverett and Wu 2017). For instance, in the case of the Jakarta–Bandung high-speed railway, Indonesia took advantage of China's impatience to promote the railway as a symbolic project to export China's HSR, thus gaining more bargaining power in negotiating project items. The bargaining power of host countries suggests that China should be more careful about the factors that may lead to local Sinophobic sentiments, which have impeded the progress of China's HSR projects.

This article contributes to the existing literature by understanding China's HSR diplomacy from an economic diplomacy framework developed by Okano-Heijmans (2011) of context, tools, process, theatre, and outcomes. The argument is built on various sources, including journal articles, news, reports, and trade and investment data. However, it was only an assumption based on secondary sources without first-hand data like interviews with relevant Chinese officials. In addition, due to Covid-19 and the extended construction period of the project, specific data like trade and investment data generated by the construction of the railways have yet to be made available. Further research could be performed to analyze the impact of China's HSR diplomacy by conducting field research and tracking operational data of Chinese HSRs operating in SEA.

REFERENCES

ASEAN Secretariat. 2022. ASEAN Statistical Yearbook 2022. Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat.

Aiddata. 2024. Global Chinese Development Finance. URL: https://china.aiddata.org/.

Aiddata. n.d. ICBC provides Rs. 1.36 billion in additional financing for the Lahore Orange Line Metro Train Project. URL: https://china.aiddata.org/projects/57673/.

Barahamin, A. 2022. ‘Infrastructure-first’ Approach Causes Conflict in Indonesia. China Dialogue, May 11. URL: https://chinadialogue.net/en/business/infrastructure-first-appro-ach-causes-conflict-in-indonesia/.

Barrett, E. C. 2014. Chinese High Speed Rail Leapfrog Development. China Brief XIV (13): 10–13.

Bräutigam, D., and Tang, X. 2011. African Shenzhen: China's Special Economic Zones in Africa. Modern Asian Studies 49 (1): 27–54.

Chan, G. 2016. China's High-speed Railway Diplomacy: Global Impacts and East Asian Responses. New Zealand, February. URL: https://www.eai.or.kr/data/bbs/eng_report/2016021517332269.pdf.

Chan, G. 2017. From Laggard to Superpower: Explaining China's High-Speed Rail ‘Miracle’. Kokusai Mondai (International Affairs) 661: 1–9.

Chaziza, M. 2019. China's Economic Diplomacy Approach in the Middle East Conflicts. China Report 55 (1): 24–39.

Chen, X. 2016. China Railway Wins $3.3bn Bangladesh Railway Deal. [Zhontie huode mengjiala tielu 33 yi meiyuan dadan]. Jiemian, March 31. URL: https://www.jiemian.com/article/593849.html (in Chinese).

Chu, L., Wang, H., and Chen, L. 2011. The Impact of High-speed Rail Operation on Xiamen's Logistics Market and Countermeasures. [Gaotie yunying dui Xiamen wuliu shichang de yingxiang ji duice]. Comprehensive Transportation 9 (September): 61–65. (in Chinese).

Couto, A. 2011. The Effect of High-speed Technology on European Railway Productivity Growth. Journal of Rail Transport Planning & Management 1 (2): 80–88.

Department of Commerce of Yunnan Province. 2022. Yunnan: Striving to Promote the Construction of a Radiation Centre for South and Southeast Asia and Building a New High Ground for Opening Up to Outside world. [Yunnan: fenli tuijin mianxiang dongnan dongnanya fushe zhongxin jianshe gouzhu duiwaikaifang xin gaodi]. May 24. https://swt.yn.gov.cn/articles/38524. (In Chinese)

Drache, D., Kingsmith. A. T., and Qi. D. 2019. One Road, Many Dreams: China's Bold Plan to Remake the Global Economy. Bloomsbury China.

Fu, C. 2016. Expert Said China-Thailand Rail Project in Flux Because of Concessions to Indonesia's High-speed rail. [Zhuanjia zhongtai tielu xiangmu shengbian xiyin dui yinni gaotie rangbu da]. Sina Finance, April 12. URL: http://finance.sina.com.cn/chanjing/cyxw/2016-04-12/doc-ifxrcizu4056950.shtml. (In Chinese).

Garlick, J. 2017. Understanding China's Railway Diplomacy. Global Times, September 26. URL: http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1068315.shtml.

Guo, W., and Huang, Z. 2023. China-Laos Railway Imports Five Times More Cargo Than Last Year. [Zhonglao tielu jinkou huowu yunliang tongbi zengzhang wu bei]. China International Import EXPO, February 27. URL: https://www.ciie.org/zbh/bqxwbd/20230227/36430.html. (in Chinese)

Global Times. 2023. China-Europe Freight Train Transport Volume up 30% during H1. Global Times, June 6. URL: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202307/1293848.shtml.

Han, X. 2014. Construction of the Pan-Asian High-speed Rail Starts Next Month From Kunming South to Singapore. [Fanyagaotie xiayue donggong jianshe cong Kunming chufa nandi xinjiapo]. The People, May 8. URL: http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2014/0508/c1001-24990040.html. (in Chinese)

He, P. 2019. China's Economic Diplomacy in 70 Years: Overall Evolution, Strategic Intentions and Contributory Factors. [70 nian zhongguo jingjiwaijao de zhengti yanbian zhanlue yitu he yingxiang yinsu]. World Economy Studies 11 (November): 3–13. (In Chinese).

HKTDC. 2005. Sharp Increase in Yunnan-ASEAN Trade in 2004. April 1. URL: https:// info.hktdc.com/alert/cba-e0504b-6.htm.

Hu, W., Liu, W., and Kwak, S. Ch. 2017. The Strategic Marketing of China High-Speed Railway: Government Behavior or Market Behavior. Journal of Marketing Studies 25 (1): 185–194.

Huang, Y., Ge, Yu., Ma, T., and Liu, X. 2017. Geopolitical Space of China's High-Speed Railway Diplomacy. [Zhongguo gaotie waijiao de diyuan kongjian geju]. Progress in Geography 36 (12): 1489–1499.

ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. 2021. The State of Southeast Asia: 2021 Survey Report. February 10. URL: https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/The-State-of-SEA-2021-v2.pdf.

Jiang, Zh. 2022. Thirty Years after the Idea of a Trans-Asian Railway Network, Southeast Asia Is Still A Scattered Mess. [Sanshi nian fanya tieluwang gouxiang, dongnanya yiran yipan sansha]. Voachiness, August 14. URL: https://www.voachinese.com/a/thirty-years-after-conception-high-speed-rails-linking-southeast-asian-... 20814/6700873.html. (In Chinese)

Ker, M. 2017. China's High-speed Railway Diplomacy. Staff Research Report, U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission (February).

Kobayashi, K., and Okumura, M. 1997. The Growth of City Systems with High-speed Rail-way Systems. The Annals of Regional Science 31 (1) (May): 39–56.

Kratz, A., and Pavlićević, D. 2017. Chinese High-Speed Rail in Southeast Asia, Reconnecting Asia. Reconnecting Asia, September 18. URL: https://reconasia.csis.org/chinese-high-speed-rail-southeast-asia.

Leverett, F., and Wu, B. 2017. The New Silk Road and China’s Evolving Grand Strategy. The China Journal 77: 110–132.

Luo, W. 2022. Country Eager to Share its High-speed Rail Experience. China Daily, August 23. URL: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202208/30/WS630d52e6a310fd2b29e74db5.html.

Martin, N. 2016. Asia's High-speed Rail Plans. Made for Minds, April 27. URL: https:// www.dw.com/en/chinas-high-speed-rail-plans-for-asia-inch-closer/a-19217479.

Naughton, B. 2015. The Transformation of the State Sector: SASAC, the Market Economy, and the New National Champions. In Naughton, B., and Tsai, K. S. (eds.), State Capitalism, Institutional Adaption, and the Chinese Miracle (pp. 46–71). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nolan, P. 2014. Chinese Firms, Global Firms Industrial Policy in the Age of Globalization. New York: Routledge.

Nugroho, G. 2015. An Overview of Trade Relations between ASEAN States and China. URL: https://www.waseda.jp/inst/oris/assets/uploads/2015/10/i2-4.pdf.

Nye, J. S., Jr. 2008. Public Diplomacy and Soft Power. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 616 (1): 94–109.

Nye, J. S., Jr., and Wang, J. 2009. Hard Decisions on Soft Power: Opportunities and Difficulties for Chinese Soft Power. Harvard International Review 31 (2): 18–22.

Obe, M., and Kishimito, M. 2019. Why China is Determined to Connect Southeast Asia by Rail. Nikkei Asia, Janurary 9. URL: https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/The-Big-Story/Why-China-is-determined-to-connect-Southeast-Asia-by....

Oh, Y. Ah. 2018. Power Asymmetry and Threat Points: Negotiating China's Infrastructure Development in Southeast Asia. Review of International Political Economy 25 (4): 530–552.

Okano-Heijmans, M. 2011. Conceptualizing Economic Diplomacy: The Crossroads of International Relations, Economics, IPE and Diplomatic Studies. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 6: 7–36.

Pan, Ch. 2012. Knowledge, Desire and Power in Global Politics: Western Representations of China's Rise. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Pavlićević, D., and Kratz, A. 2017. Testing the China Threat Paradigm: China's High-speed Railway Diplomacy in Southeast Asia. The Pacific Review 32 (2): 151–168.

Priemus, H. 2009. Do Design & Construct Contracts for Infrastructure Projects Stimulate Innovation? The Case of the Dutch High Speed Railway. Transportation Planning and Technology 32 (4): 335–353.

Qin, F. 2021. What Happened to Vietnam and India When They Chose Japan's High-speed Rail Instead of China’s? [Yuenan yindu dangchu buxuan zhongguo gaotie, faner xuan riben, xianzai zenmeyang le]. Zhihu Zhuanlan, December 29. URL: https://zhuan-lan.zhihu.com/p/451364646. (In Chinese)

Reuters. 2021. China and Laos Open $6 Billion High-speed Rail Link. Reuters, December 4. URL: https://www.reuters.com/markets/deals/china-laos-open-6-billion-high-speed-rail-link-2021-12-03/.

Rosales, E. F. 2022. China Wants 3% Interest on Philippines Railway Projects Loan. Philstar Global, July 22. URL: https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2022/07/16/2195708/china-wants-3-interest-philippines-railway-pro....

Shambaugh, D. 2015. China's Soft-Power Push: The Search for Respect. Foreign Affairs 94 (4): 99–107.

South China Morning Post. 2016. ‘China's High-speed Railway Project in Indonesia Suspended Over Incomplete Paperwork. South China Morning Post, January 27. URL: http://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy-defence/article/1906307/chinas-high-speed-railway-project-i....

South China Morning Post. 2017. China to Get Rolling on Stalled Indonesia High-Speed Rail Line. South China Morning Post, March 25. URL: http://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy-defence/article/2081968/china-get-rolling-stalled-indonesia....

Scobell, A. 2018. Why the Middle East matters to China. In Anoushiravan, E., and Niv, H. (eds.), China's Presence in the Middle East: The Implications of the One Belt, One Road Initiative. London: Routledge.

Sejko, D. 2016. Financing the Belt and Road Initiative: MDBs, SWFs, SOEs and the Long Wait for Private Investors. Paper presented at the International Conference & International Forum on ‘China's Belt and Road Initiative: Recent Policy Development and Responses from other Countries’. Lingnan University, December 2–3.

Tjia, Y. N. 2020. The Unintended Consequences of the Politicization of the Belt and Road's China-Europe Freight Train Initiative. China Journal 83: 58–78.

van Bergeijk, P., A. G., Okano-Heijmans, M., and Melissen, J. (eds.) 2011. Economic Policy: Economic and Political Perspectives. The Netherlands: Brill. URL: https://brill.com/edcollbook/title/20423.

Wang, H., and Jia, W. 2017. Foreign Media Views on the Belt and Road Initiative. [Waiguo meiti kan yidaiyilu]. China: Social Science Academic Press. (in Chinese)

WITS – World Integrated Trade Solution. n.d. Trade Statistics by Country / Region. Data. URL: https://wits.worldbank.org/countrystats.aspx?lang=en.

Wikipeida. n.d. China–Pakistan Economic Corridor. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/China%E2%80%93Pakistan_Economic_Corridor#Finance.

Xing, W. 2023. Vietnamese Prime Minister Asks Japan for US$64.8 Billion to Build Highspeed Rail. Seetao, January 19. URL: https://www.seetao.com/details/199627.html#:~:text =17%20years%20of%20high%2Dspeed%20rail%20without%20a%20trace&text=Fan%

20Min-gzheng%20said%20that%20the,a%20similar%20request%20to%20Japan.

Xu, F. 2018. The Belt and Road: The Global Strategy of China High-Speed Railway. Singapore: Springer.

Yan, X. 2014. From Keeping a Low Profile to Striving for Achievement. The Chinese Journal of International Politics 7 (2): 153–184.

Zhang, Zh., and Sun, F. 2016. Focus on Supply-side Reform: Seven Initiatives to Address Excess Overcapacity. [Jujiao gongji ce gaige: sanda qida jucuo huajie channeng guosheng]. The People, February 23. URL: http://finance.people.com.cn/n1/2016/0223/c1004-28143867.html.

Zhao, D., and Zhang, J. 2012. Research into Spatial Pattern Changes of Yangtze River Delta's Accessibility Under the Impact of High-speed Railways. [Gaosu tielu yingxiang xia de changjiang sanjiaozhou chengshiqun kedaxing kongjian geju yanbian]. Resources and Environment in the Yangtze Basin 4 (4): 391–398.

Zhao, Y. 2014. Scenario Analysis of the Impact of the Construction of the Pan-Asian High Speed Rail on the Economic Linkages between Yunnan Province and the Central South Peninsula [Fanya gaotie jianshe dui yunnansheng yu zhongnan bandao jingji lianxi de qingjing fenxi]. Master Diss., Nanjing Normal University. (In Chinese)