Symbolic Orders and the Structure of Universal Internalization

Almanac: Evolution:Evolutionary Trends, Aspects, and Patterns

Abstract

Big History is a theoretical field attempting to ground a historical evolutionary view of the physical universe. However, in this paper the author argues that such a view by necessity can only remain on the first order of discourse. In the first order of discourse the observer remains external to the system objectively under reflective observation. This approach has proven effective and useful but remains limited in terms of understanding the evolution of the symbolic order. Internal to the symbolic order networks of observers produce and maintain their identities via mechanics of reflection that are independent of any external systemic objectivity. Consequently, in this work the author explores the potential for Big History to approach the problematics of a higher order framework inclusive of observers. The main goal of this approach is to understand the ways in which symbolic orders evolve across time reflectively transforming visions of past and future.

Keywords: Big History, philosophy, futures, cybernetics, systems.

Narrativization of Universal Evolution

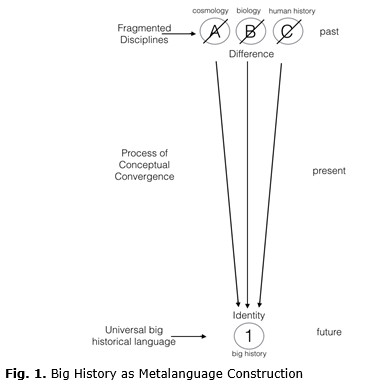

Big History is a subject that formally emerged to meet and potentially satisfy a general desire for a symbolic space capable of holistically integrating fragmented scientific disciplines from cosmology to biology to human history (Christian 2017). Consequently, the ultimate goal of the study of Big History is to create a common language for all academic research so that seemingly disparate phenomena can be understood in an integrated framework (Spier 2017). From this perspective all disciplines, irrespective of their object of analysis on the various scales of reality, are all a part of the Big Historical narrative from ‘Big Bang to Global Civilization’ (Rodrigue et al. 2012).

In this way, as Big History pioneer David Christian conjectures, the aim of Big History is to conceive of a ‘grand unified story’ capable of reclaiming the human desire for a total vision of reality (Christian 2004: 4). This desire has not been satisfied by the hyper-fragmented structure of the 20th century knowledge. Thus, Big History at its most fundamental ground seeks to construct a symbolic order in the form of a temporal narrative (past-present-future) that can reconcile a totalizing understanding of substance (Big Bang to global civilization). One may refer to this desire as the desire for a naturalist ‘metalanguage’ (Evans 2006) capable of transdisciplinary integration (Heylighen 2011). Can human beings converge on an understanding of the structure of substance and its development from its initial emergence to its contemporary actuality? (see Fig. 1)

In the contemporary Big Historical ideal a metalanguage would mean that researchers from any discipline would have the linguistic tools necessary for any problem related to the universal historicity of being. From this ideal we would have a convergence of empirical methodology and conceptual terminology in the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities (Wilson 1998). This is an unresolved problem that has long plagued contemporary academia (Snow 1959; Kauffman 2010). To be specific, a convergence of method and language appears to become beyond reconciliation when we focus on Big Historical eras or epochs of significant qualitative change. For example, in the emergence of spacetime there is contention between theology and physics (Drees 1990), in the emergence of life there is contention between physics and biology (Luisi 2016), in the emergence of humans there is contention between biology and general humanist discourse (Rose H. and Rose S. 2010).

However, the aims of Big History go even one step further. Indeed, it is believed that if we could successfully develop a metalanguage, we would also have a potential convergence of modern global subjective identity and aims. Here we can imagine a world with all humans reflecting on the historical structure of being and contributing to its understanding in or towards a future unified knowledge foundation. Indeed, the desire for a unified knowledge foundation for understanding is something that has structured the whole core of philosophy (Plato 1998; Hegel 1998) and ‘anti’-philosophy (Kuhn 1962; Foucault 1972). Thus, the belief that humans could develop a unified language for knowledge is something that is either viewed as the penultimate quest of reasonable human telos or the penultimate mad delusion internal to human reason.

Considering the discipline of Big History situates itself on the philosophical side of reason in the pursuit of unified knowledge we have an accompanying attempt at a totalizing narrative. As the contemporary story goes, ‘In the beginning…’ there was nothing (an empty substanceless void), and from this nothing, there emerged not just a positive substantial something, but everything we can observe and detect with our technological extensions, from the tiniest subatomic scales to the largest super-galactic scales. This is Big History between nothing and everything (Christian et al. 2011). It is in the sense of this narrative that, where other disciplines would seek specialization, Big History aims for a theoretical edifice that would achieve a holistic comprehension, or at least work in the direction of holistic comprehension (Spier 2017).

In the Big Historical narrative what connects the unimaginably inhuman scales of subatomic, super-galactic space, and everything in between, is the progressive evolution of complex structure in our local region (Aunger 2007a, 2007b). The cosmic evolutionary understanding refers to this complex structure as the materialist hierarchy of interconnected forms (Smart 2008). Thus, in this framework what unites the ‘micro-macro’ worlds of the physical universe to the ‘middle’ world of the human symbolic orders is the ‘evolution of complexity’ in terms of diverse parts (elements) capable of connecting (relating) in higher coherent wholes. These wholes in turn exhibit structural forms with novel properties, from macromolecular chemical communities to the technological global human community.

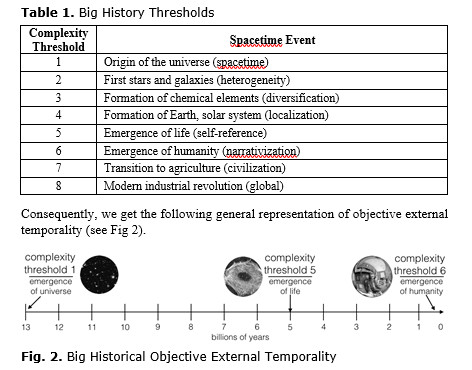

Consequently, the concrete theoretical interpretation of the Big History story relies on the structure of complexity science. Here we can read a story articulating the notion that our universe undergoes fundamental transformations described as ‘complexity thresholds’ (Christian 2008). Complexity thresholds occur when a form of structural organization emerges and stabilizes a novel regime of phenomena (a new level of the materialist hierarchy). Dominant descriptions of these complexity transitions have been grounded in either an informational base (universal complexity as best understood in algorithmic terms) (Baker 2013), or with an energetic base (universal complexity as best understood in thermodynamic terms) (Spier 2005). In these respective frames we seek to understand the way in which the universe generally processes information and the way in which the universe generally organizes energetic flows of matter.

The most common linear demarcation of these information-energy complexity thresholds into a universal narrative includes the following fundamental distinctions (see Table 1).

From these frameworks some Big Historians

have started to speculate on how this historical theoretical approach can help

us understand the complex dyna-

mics of contemporary civilization in regards to

predicting the future of our informational and energetic capacities and

organization (Spier 2010). Such speculations are being articulated with notions

of an immanent ‘Complexity Threshold 9’ characterized by various utopian or

dystopian structural possibilities depending on human decision-making (Voros

2013; Simon et al. 2015). How should Big Historians approach this futures threshold of

immanent possibilities? Can we approach this future horizon with the same

epistemological structure that we have approached an understanding of the

substantial material past?

The question here is one of the nature of historicity itself and its ontological utility for future's speculations (Hofkirchner 2017). If we assume that Big History has succeeded in developing the epistemological tools capable of helping us understand the emergence of complexity, does this necessarily translate into an understanding of future's reality? To be specific, in understanding the rise of novel structure and order in the world, do we see the emergence of a metalinguistic knowledge foundation to unify all meaningful observation? Can our contemporary Big Historical complexification narrative become the dominant narrative structure for universal being in relation to all future observers? What does Big History make of alternative universal narrativization? What does Big History make of the ecology of competing narrativization? What does Big History make of its own historical narrative grounding and actualization? Moreover, does the Big History narrative really claim that once we have integrated our historical evolutionist knowledge of the past that the direct consequence will be a unified global modern subjectivity?

In order to approach these issues let us consider the fact that, for the substantial material past (where we do observe an interconnected complexification) we can simply reflect on the processual content that appears to us as observers and then inscribe this processual content into a symbolic order framing reality (complexity science, cosmic evolution, etc.). Thus, it may seem to be the most logical possible movement to ground an actual Big History community in frames that can handle a futures complexification (Last 2017a). This may be considered as a historical evolutionary view of the physical universe where the observer remains external to the system objectively under reflective observation. Indeed, in some sense, there is no differentiation of Big History from this historical evolutionary frame of reference (Chaisson 2011a, 2014). In what sense is Big History different from, say, cosmic evolutionary theory? Does it need to be?

Evolution of Narrativistic Internalization

These questions require us to consider what happens to the Big Historical observer internal to the cosmic evolutionary process (Last 2018). To be specific, what happens to the external observer of the system objectively reflecting observation (i.e., the Big Historian) when we must consider the immanence of the observer internal to the system transformed by epistemological constructs or ‘narrativization’ (i.e., the action of the global modern subject)? In short, what happens when we no longer consider the observer as passively reflecting being but actively synthesizing being? (Dieter 2008) What happens when the self-loop of presuppositions becomes entangled with the actuality of becoming? What happens when what the observer presupposes becomes itself reflectively formed as actual being? This is a situation where what is the actuality of being is not passively reflected by observers but where what is the actuality of being is something constructed by the totality of reflective observers.

This problem can be presented precisely and clearly as a perspectival shift that does not require the positing of new substance but the positing of new narrative emphasis. Thus, this perspectival shift does not challenge the temporal history of complexity thresholds, but notes that throughout this temporal history of complexity thresholds, the universe has started to ‘internalize’ itself through a ‘progressive’ synthesis or sublation of itself. In order to capture this process of universal ‘internalization’ we can say that the complexifying universe started to form a minimal level of internal self-relation (Maturana and Varela 1991). What are the consequences of this progressive internalization? How is it connected to complexification? How should we understand the complexity of narrative given its irreducibly internal nature?

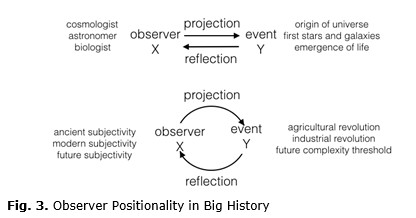

Indeed, the very emergence of a Big History community represents this synthetic sublation process of internalization where the universe attempts to conceptualize itself as a totality. What we seek here to do is put a narrative emphasis on the consequences of this internalization motion as something of significance to future Big Historical research. In order to situate an understanding of this internalization process let us consider the relation between observer X and event Y. When observer X (cosmologist, astronomer, biologist) projects and reflects on event Y (i.e., origin of universe, formation of stars /galaxies, emergence of life), observer X does not change event Y. In other words, irrespective of the actions of observer X (scientific subject), event Y (physical universe) does not change its course of action.

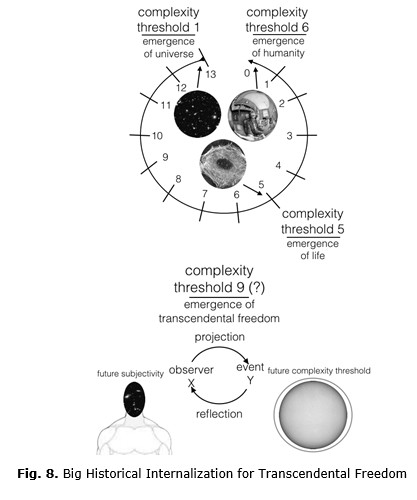

However, the closer we get to the real of human history (i.e., what Big History demarcates as Complexity Threshold 7–9), the more obviously we are dealing with a phenomenon where all observers X projections and reflections are responsible for event Y. Indeed, as for the real of past historical transitions like the agricultural or industrial revolutions (i.e., Complexity Thresholds 7 and 8), event Y becomes nothing but the collective activity of observers X. The agricultural and industrial revolutions are not events constituted in an observer-less, narrative-less realm, but irreducibly within and by observers constituted by narrative self-action. The difference here for the Big Historical future is that for Complexity Threshold 9 the observers are ‘meta-aware’ of their narrative position in the Big Historical drama (see Fig. 3).

How are we to interpret this Big Historical fact? Big Historical interiorization during complexification suggests that complexification is somehow related to interiorization, of the universe becoming increasingly conscious of itself (Teilhard de Chardin 1955). Consequently, the passive reflection correspondence between human epistemological constructs (i.e., Big History narrative) and the ontological nature of reality (i.e., physical evolution of universe) becomes simply untenable in relation to the future of the present moment. For example, in contemporary science the inadequacy of passive epistemological reflection becomes unavoidable when reflecting on the future of conscious and technological evolution (Kurzweil 2005), the connections between physics and computation (Lloyd 2006), and a future physics dependent on observation (Smolin 2001).

In all of these contemporary scientific domains we are dealing with a situation where epistemological constructs or narratives must be inscribed into the ontological nature of the thing under observation. For example, technological singularity theory is a narrative that becomes directly involved with itself in the creation of the technological singularity; quantum computational theory is a narrative that will itself generate technologies of immanent universal consequence to all observers (even if no one knows what these consequences will be); and modern quantum gravity narrativization requires a way to reconcile observation with the strange dynamics of curved spacetime. The irreducible commonality to all such scientific problematics includes interiorization: What is reality inclusive of observation? What is reality inclusive of narrative?

Thus, in order to properly grasp how the universe internalizes itself through its complexification understanding the nature of observation is something that Big History must confront seriously. In creating a grand narrative architecture for complexification we do achieve a sense of holistic unity with universal being. However, there is a real sense in which this obfuscates the real of observational dynamics and narrativization. To confront this problematic I propose that we must be able to think a Big History where the human observer X (the constructor of a Big History) becomes, as an ontological fact, a direct causal agent in the materialist chain of events Y (the future evolution of the universe), and not merely an epistemological effect of empirical material phenomena (Last 2018).

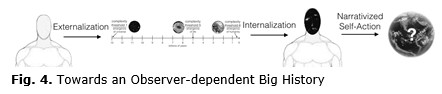

This means that the narrative is directly responsible for facilitating the becoming of being itself: not a story about being but a story that constitutes being itself (Žižek 2012). In this sense, perhaps, the point of the Big History community is not merely to reflect on the totality of being (where observer X reflects positive content Y), but to engage in the necessary meta-reflection on why there exist beings who narrativize the whole of being? One can say that Big History reflects objective nature; one can also say that Big History cognitively transforms the conscious elements narrativizing being. Thus, in accordance with the literature pointing towards Big History as a social movement (e.g., Katerberg 2018), one can ask whether Big History serves the evolution of the modern global subject epistemologically, and one can also ask whether the modern global subject serves Big History ontologically. To what end? What is the Big Historical mission that a cosmic synthetic sublation should tend towards? (see Fig. 4)

In order to consider these questions we must operate on the level of the becoming of ideational beings (Kojève 1980). In terms of the standard Big Historical complexification nature differentiates itself in higher order integrations. But when reaching the level of ideational internalization we have nature reflectively exploring itself through the ideas of free externalization (Big Bang to global civilization) and then returning to itself (modern global subject). What are the action-based consequences? How does the modern global subject who has internalized the whole of nature change modern global society? Is there a thinkable universality that emerges that actually transcends mere reductions to an observer tethered to scientific reflection correspondence?

In this perspective of Big Historical internalization the conflict or tension between the modernist scientific constructionist view seeking universal totality and the postmodern critical view seeking to deconstruct universal totality seem to gain new dimensions. Indeed, in the same way that many contemporary scientific projects have an issue of what to do with an observer-dependent understanding of science, is not the main challenge that postmodern social critique poses to modernist scientific construction the general issue of reality when one also wants to consider the way reality is entangled with internal observational narrativization? (Lyotard 1984)

This is not to say that contemporary sciences like quantum gravity focused on the external real are merely social constructions (as has been adequately parodied [Sokal 1996]), there is an external real here (the real of black holes, Big Bang, etc.) (Frolov and Zelnikov 2011). However, there is also the real of observationally constituted narrativization that cares about the real truth of quantum gravity and this is always left out of the model (Last 2018). Here one can say clearly and concretely that this divide may primarily be a divide between the real of the external objective material constitution of the world, and the real of the internal subjective action in the world. When we think of the consequences of narrativized internalization for the next big historical complexity threshold we are dealing with an irreducible entanglement of these two reals as if narrativized observers are repetitively centering themselves around the truth of being.

Research Focused on Narrativistic Internalization

The postmodern challenge to modernist scientific narrativization is here the issue of a historically unreflective totalization of the narrative (Kuhn 1962; Foucault 1972). In modernist thought it is possible to conceive a narrative that captures the whole of temporal substance towards a universal metalanguage (‘Big Bang to global civilization’). However, in post-modernism there is no ‘one’ narrativistic reconciliation or scaffolding for totality (Derrida 1997). This is for simple yet complex reasons related to the reality of internalization: the narrative is irreducibly contingent in relation to its particular historical disclosure (i.e., what dimensions of being we can observe) (Heidegger 1988), its particular sociohistorical instantiation (i.e., a discourses regime of symbolic social power) (Foucault 1980), and its subjective interpretational symbolic meaning architecture (i.e., the irreducible personal value or utility of the narrative for a mortal and finite self-consciousness) (Peterson 1999).

Here, as regards the Big History community, we must be able to think how future understanding of being will change Big Historical narrativization, how Big Historical social power instantiation effects narrativization, and how this narrative functions for the individuation or transindividuation process. In that sense the phenomenological instantiation of one master narrative of being, from Biblical narrativization (Sternberg 1987) to Newtonian narrativization (Goldstein 2011), to Marxist narrativization (Lukács Ge. and Lukács Gy. 1971), to Big Historical narrativization (Christian 2004), is a problem that cannot stand when one thinks of the observer within the system. The master narrative is only possible when one operates under the fantasy that the observer is external to the system. In that sense we must always leave room for the way in which the observer's totalizing understanding is never itself totality.

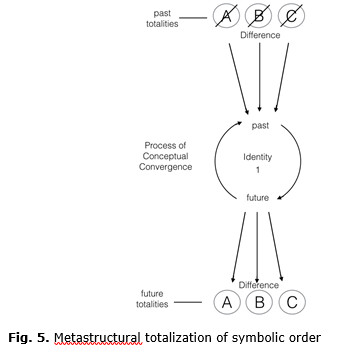

This gives us a different view than the view that conceptual coherence is a process whose past is fragmented and whose future is unified in a metalanguage. To be specific it gives us a view that totalization of temporal substance is always something that subjectivity repeats in the present moment (reducing both past and future to the narrativistic present). Here we get a view of the narrativistic temporality of the subject (Ricoeur 2010). In this sense past humans engaged in symbolic totalization (e.g., Biblical, Newtonian, Marxist, etc.), and we are continuing this evolution of symbolic totalization with new/different content (in the Big Historical sense, the content of cosmic evolution and the theory of complexity science). Thus, when the observer is within the system we must attempt to think the psychoanalytic ‘metastructure’ of the symbolic order. In this metastructure there is no unifying ‘metalanguage’ between particular historical subjectivities that would unify knowledge of being (see Fig. 5).

However, the impossibility of metalanguage does not necessarily leave us in pure discursive relativity of infinite possible interpretations of the world (i.e., ‘all interpretations are valid’). There is a possibility that the metastructure of the symbolic order and the narrativistic present is somehow related to ethical-political directives (or backgrounds) that must be stabilized across time. These ethical directives/backgrounds are by no means relativistic, but rather, absolute (Jameson 2013). Indeed, what we often find in the ethical-political directives of symbolic orders is often an invariant desire expressed under conceptual unity independent of particular historical instantiations of narrative frame (i.e., Biblical, Newtonian, Marxist, etc.). This would support the hypothesis that by narrativising the present moment linguistic observers or self-consciousnesses repetitively totalize temporal substance in order to center themselves (‘gravitationally’) in being (Dennett 2014). In that sense our attention moves to this process of how conceptual unities orient the background field of historical observers.

Here we can take a moment to consider a few examples related to Biblical (theological), Newtonian (scientific), and Marxist (political) narrativization. The Biblical narrative centers subjectivity in relation to a past ‘Eden’ and a future ‘God’, the Newtonian narrative centers subjectivity in relation to an ‘Eternal Spacetime’ (with no beginning and no end), the Marxist narrative centers subjectivity in relation to a past ‘Primitive Communism’ and a future ‘Global Communism’. This is not to say that any of these narrativistic temporalities are literally true in a materialist sense (i.e., ‘Eden/God’, ‘Eternal Spacetime’, ‘Primitive/World Communism’). However, it is the case that these narrativistic temporalities are metaphorical truths for subjectivity that have stabilized action in the realm of history. Furthermore, these metaphorical truths have had real material consequences in the establishment of Christian, Physicalist, and Communist societies.

For our Big Historical purposes one can start to see the temporal ‘metastructure’ of the symbolic order independent of whether the symbolic order is instantiated relative to a theological, scientific, or political directive/back ground. One can also start to reflect on how our own Big Historical ‘literal’ totalizing substantial temporality (past ‘Big Bang’ and future ‘global civilization’) may be something that we retroactively come to discover is only a particular narrativization of being in the larger becoming of the concept. How will future subjectivity narrativize the whole of being? Will we discover that the Big Bang is a particular phase transition part of a larger more complex process? Will global civilization transform itself into an entity beyond human comprehension? Or, indeed, one can ask: how does Big History's temporal metastructure operate on its own ‘absolute’ ethical political background directive? Do Big Historians actually operate on this ethical political background directive? Do they reflect deeply enough on this ethical political background directive? Are there alternative possible ethical political background directives?

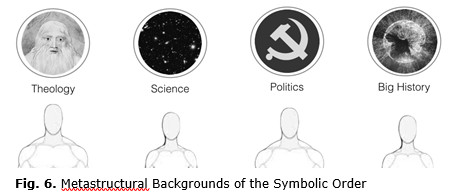

These are what we may call ‘higher order’ internalization issues of the symbolic order. When Big Historical researchers approach the transition of ‘Complexity Threshold 8 to 9’ (global modern civilization to?) we must be able to confront the relation between complexification and internalization. In this context we are focusing on the way in which the universe is progressively synthesizing or sublating itself in unified but competing and antagonistic conceptual forms as absolute backgrounds. In this mode the first step, as mentioned, may be to focus on a meta-reflection of Big History as a movement culture (i.e., the processual action of narrativized beings). Thus, in the same way that the Biblical narrative centers subjectivity in relation to God, or the Newtonian narrative centers subjectivity in relation to Spacetime, and the Marxist narrative centers subjectivity in relation to Communism, we may say that the Big History narrative attempts to center subjectivity in relation to the reconciliation of planetary civilization (see Fig. 6).

Does this require us to more seriously introduce psychoanalysis into Big History? (Blanks 2016) In psychoanalytic terms we may call these metastructural background directives. ‘Others’ that stand-in for the impossibility of a universal metalanguage. These ‘Others’ come to be conceived of by the subject as absolute complete and consistent languages which guarantee ethical political action. Thus, the subject of Biblical narrativization has no doubts about the necessity of reconciliation with God (in terms of understanding his Will), the subject of Newtonian narrativization has no doubts about the necessity of reconciliation with Spacetime (in terms of understanding its mechanics), the subject of Marxist narrativization has no doubts about the necessity of reconciliation with Communism (in terms of understanding its determination).

In relation to the aforementioned meta-antagonism of modernism and postmodernism one can see that thinking the external objective materialist real and internal subjective action based real together does not merely relativize the Big Historical narrativization project, but rather, absolutizes it internal to observer-dependent historical process. In other words, this is not a standard interpretational situation where one totalizing modernist scientific metalanguage (Friedman 2005) stands opposed to an egalitarian ancient multiplicity of narrative epistemologies (Davis 2009). Instead this higher order focus is on the way in which Big History in its current representations ‘metastructures’ a particular formal epochal disclosure of being.

When we think of Big History in these terms we are thinking in terms of a narrativistic desire for a future complexity threshold that results in a harmonious global order (Spier 2010). In that sense we cannot understand contemporary Big History ‘objectively’ independent of its contextual emergence within our postmodern information age with all of its problems and antagonisms (Last 2017b). We cannot think of contemporary Big History ‘objectively’ independent of its possible failure to reconcile planetary civilization and help instantiate a totally other observationally narrativized world. It is in this sense that we think of Big History as not simply a story about being but a story that constitutes (this temporal era of) being itself. It is in this sense that the Big History narrative is conceived as an integral part of the larger conceptual becoming of the concept itself. Can Big History think this concept in its becoming?

Higher Orders of Universal Internalization

There is an important form of dynamical flexibility when we think of Big History in terms of the evolution of symbolic orders. The most obvious example is related to reflecting on the transcendental horizon that structures a big historical frame. In this sense, instead of assuming the objective real of a materialist hierarchy governed by the progressive constitution of complexity thresholds, we ask what is being centered or oriented in the modern global subject by the complexity threshold framing perspective? Beyond a desire for harmonious global reconciliation are we preparing epistemologically for some sort of qualitative transition in our experiential structure? (Barrat 2013; Bostrom 2014; Kaku 2014). Indeed, as one can argue that Big History tends towards higher levels of complex integration (like a harmonious global civilization) (Spier 2010), one can also argue that Big History tends towards higher levels of experiential qualities (Last 2017a).

Towards the possibility to think this within Big History we may note that in past complexity thresholds (e.g., 6 and 7) there have not only been quantitative increases in information processing (Delahaye and Vidal 2016) and energy flows (Chaisson 2011b), but also qualitative changes in internal experience (Thompson 2010; Deacon 2011). In the human realm there have been qualitative changes related to the emergence of beings with ideational-notional capacities (not just apes, but subjects of the dialectic of self-consciousness [Hegel 1998]) and the emergence of beings with exceptional ideational-notional determination (not just humans acting like apes, but subjects of the Overman [Nietzsche 1883]). Is the next qualitative transition beyond the human as has been discussed in much of the contemporary speculative futures literature (Vinge 1993; Kurzweil 2001; Goertzel B. and Goertzel T. 2015)? What does Big History have to add to this speculative futures literature? Can Big History understand how new ethical-political centers of being (God, Spacetime, Communism, etc.) tend towards stabilizing new totalizing narrative temporalities via ideational-notional determination? What are the mechanics of such conceptual background formation?

In this sense we call attention to higher order evolution of the symbolic order. Symbolic orders create and transform the processual content of our future through a multiplicity of frames of reference. Indeed, within this meta-level field some of these narrative frames are historical evolutionist centering on global unity via complexification (Heylighen 2014). However, we also find narrative frames that are physical eternalist centering on the true nature of spacetime via mathematical reduction (Penrose 2004), ideational eternalist centering on the true nature of love via emotional transference (Sloterdijk 2011), discursive relativist centering on the nature of free subjectivity via identitarian activism (Barry 2017), metaspiritualist centered on the nature of global becoming of subjective actualization (Kripal 2007), self-referentialist centered on deconstructing or identifying the core of subjective experience itself (Metzinger 2004; Hofstadter 2007), or traditional religious centered on the presence of God (Barth 2003).

Although all of these symbolic orders are not necessarily in ontological contradiction or conflict, many of them are. For example, there is no obvious ontological contradiction between the historical evolutionist view and the self-referentialist view. One can simultaneously hold without internal contradiction or incoherence the evolution of all material and the fictional nature of subjectivity. However, there is contradiction and incoherence between the ideational eternalist view and the discursive relativist view. One cannot hold the eternity of ideal truth and the relativity of discursive construction. How do we understand their internal narrativistic interconnections or how to reconcile their differences? Here to confront the action-based real of the transition between Threshold 8 and 9 we also have to confront the real of a narrative temporality internal to the subject and the consequences of its centering (‘gravitational’) formations. To be constructive on the level of metastructure without utilizing a totalizing metalanguage can we consider the epistemological orders of cybernetics as a structuring moment for an ontology of the symbolic (see Table 2)?

Table 2. Higher Orders of Symbolic Evolution

|

Order |

Description |

Discursive Level |

|

1 |

In the first order of cybernetics we are attempting to think the external physical world as it is in itself. For contemporary Big History this would be something like the ‘big bang to global civilization’ narrative |

Physical sciences; Knowledge of the world |

|

2 |

In the second order we are thinking of the observer's relation to the external physical world as it is in itself. For our purposes this would be a particular Big History researcher's relation to the Big History narrative |

Deconstruction, |

|

3 |

In the third order we are thinking of the observer's relation to its own internal states of mind including conscious images, visions, symbols, and so forth. For our purposes this would be the genesis of representational modes to relate to self and world |

Psychoanalysis, Self-knowledge |

|

4 |

In the fourth order we are thinking of the observer's relation to the social-historical world and the way in which a self-narrative structures or centers its conception of time and direction of action. For our purposes this would be the self-action of a Big Historian or a Big History community |

History, Sociology; Self-knowledge, its action and consequences |

|

5 |

In the fifth order we are thinking of the totality of observational relation to the social-historical world and the way in which the totality of self-narratives structure or center conception of time and direction of action. For our purposes this would be the self-action of all historical narrativization |

Religion, Philosophy; Self-society know- |

The higher order focus here becomes self-action on the level of historical totality. In the inclusivity of each order we must reflectively take into consideration more observation and more of the consequences of observation internal to the system. The external world thus loses its objective quality and gains a complex matrix of multiple internalizations. However, as mentioned, this complex matrix is not ‘infinite’ in its possible viable interpretations, but rather must possess a metastructure that limits the range of interpretation. In that sense we have to consider all of the possible configurations of the totalizing backgrounds that a finite and mortal self-consciousness would situate as its absolute ethical-political directive in relation to. For example, what is the metaphysical background of the ideational eternalist and how does it differ from that of the discursive relativist? How can both be situated as viable interpretations of being? In order to answer this question we also have to consider what this matrix of symbolic backgrounds is ultimately attempting to reconcile on the terms of the observer's desires.

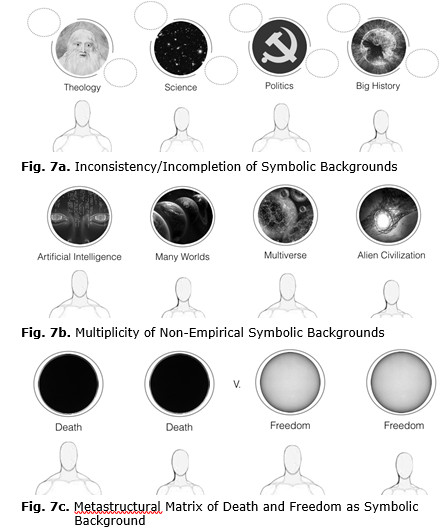

Thus, there may not be a metalanguage unifying all modern global subjects but rather a unified metastructural matrix of symbolic desire expressed temporally as a part of the becoming of the concept. What is common to all of these symbolic orders independent of the way in which they reflect material content (i.e., objective external real) and the way in which they direct a particular ethical-political action (i.e., subjective internal real)? We can, of course, say that each symbolic order is stabilized by its ‘Other’ or Background (i.e., God, Spacetime, Communism, etc.), but we can also say that every ‘Other’ or Background is not only different but internally inconsistent and incoherent (Žižek 2012). This means that the problem of the inconsistency and incoherence between certain views becomes its own solution, since ultimately, each view cannot map totality. Consequently, the impossibility of a true Other/Background is actually the positive liberating condition for the construction of any Other/Background whatsoever (see Fig. 7a).

We see that the problem of the ‘true’ or ‘real’ Other/Background is more and more a feature of the symbolic order in terms of what is often referred to as ‘post-Truth politics’. Indeed, science itself cannot escape this problem considering that many scientists are themselves starting to act in relationship to Other/Backgrounds with no empirical correlate. In this sense we see that all that is required for a subject to act in relationship to a non-empirical Other/Background is an internally consistent theoretical edifice that satisfies the reason of a particular form of historical subjectivity. For example, what types of Big History narratives must be considered if we are acting, not in relationship to the historical real of complexity thresholds, but instead in relationship to the Multiverse Universe of all possible configurations of physical law (Wallace 2012)? Or the Many Worlds Universe of all possible materialist branching directions/decisions (DeWitt and Graham 2015)? Or the Artificial Intelligence Universe of qualitatively other forms of observation (Bostrom 2014)? Or the Alien Civilization Universe of higher intelligent constitution of being (Vidal 2014; see Fig. 7b)?

However, considering that every symbolic order is ultimately stabilized by a finite and mortal self-consciousness, can we see that what is reflected in this Other/Background is something missing in being? Could it be that what is reflected in this Other/Background is some fundamental absence (Deacon 2011)? Thus, in the same way that solutions to quantum gravity may require physicists to remove their dependence on an absolute background existing independently of observation (Smolin 2001), could it be that understanding the immanence of Threshold 9 requires Big Historians to play with the consequences of background independence? In the same way that we start the contemporary Big History with a void that is filled in with all substance (i.e., “‘In the beginning…’ there was nothing [an empty substanceless void], and from this nothing, there emerged not just a positive substantial something, but everything”) can we say that all forms of historical subjectivity are desiring voids that freely fill in this absence with the necessarily missing substantial content?

In that sense the metastructure of the symbolic order would emerge around a capacity for higher action: what we may call ‘freedom’ as the ability to determine one's own reality. The real of freedom would here be juxtaposed against the constraining (and undeconstructible) background real of finitude and mortality: what we may call death as the fundamental limiting condition for any symbolic order whatsoever. In this situation, the formation of a particular ‘Other/Background’ within the metastructural matrix of the symbolic order would be dependent on the way in which a particular finite-mortal self-consciousness conceptually recognized desire for freedom against the background of its own imminent disappearance (see Fig. 7c).

Radical Speculation on the Nature of Freedom

Here I want to attempt to put a Big History

focused on universal internalization into a radical dialogue. Could it be that

it is possible to put ‘Complexity Threshold 1’: the origin of universal

spacetime as a physical container for consciousness; against its most radical

opposite for ‘Complexity Threshold 9’: the immanent desires of conscious

freedom? In this situation the symbolic order, through its progressive

conceptual syntheses, may be attempting to internalize its external otherness

so that it can return to its own notion, its own free state of being, where it

can freely constitute external otherness? From this presupposition the

universal ethical-political background directive of the symbolic order (its

most totalizing internalization) would be the most radical form of freedom

thinkable: the freedom from a determining spacetime matrix itself (the way

in which our consciousness is conditioned by finitude and

mortality as opposed to infinite and immortal unity with God). Is it possible

to think a conscious removal of such fundamental limitations? Is it thinkable

for consciousness to habitually set its own fundamental limitations?

First, let us consider the foundational epistemologies in modern sciences and humanities. In the modern sciences an understanding of external objectivity is situated under an ontological regime of absolute spacetime. This is a Newtonian epistemology that we still carry with us today even if it has received post-classical modifications (i.e., general relativity, quantum mechanics). These post-classical modifications open the possibility of ‘absolute’ spacetime itself undergoing phase transitions in extreme forms as a consequence of action density. In other words, spacetime itself evolves, and changes (as is recognized by the contemporary Big Historical narrative). In that sense we can now think of action constituting spacetime itself (i.e., complexity thresholds actively creating), as opposed to action occuring in spacetime (i.e., passively receiving complexity thresholds).

Now, when we think of foundational epistemology in the humanities is not the first gesture an understanding of internal objectivity under a regime of absolute freedom? This is a Kantian epistemology that we still carry with us today even if it has received post-Kantian modifications (i.e., Hegelian negativity, Freudian unconscious). Here can we think of human subjectivity as unconsciously negating the present moment with symbolic orders (temporalization of all substance) that tend towards self-actualization or self-realization? Here human subjects are conceived as the actors of a narrative capable of actualizing-realizing themselves against nothing but their own (free) self-posited background. In this system everything falls except for the repetitive insistence (the infinite immortal repetitive insistence) of the symbolic order to instantiate itself as a true reality.

Thus, we come to the ultimate possibility of a higher order Big History focused on universal internalization. In this frame Big History can move from first order narrativization within the evolution of spacetime as Threshold 1 to the higher order narrativization of observers tending towards absolute freedom as Threshold 9. What are the ultimate consequences of universal self-narrativization as a gravitational force? When we think of the totality of narrativized self-action in the historical process, is it not possible to think that future observers will be able to lift the present moment to a state of freedom so radical that spacetime itself will fall away? Is the point of internalizing all temporal substance to ultimately release it in a state of eternal freedom? Indeed, in the highest states of human creative self-action the subjective experience of eternity is often experienced as most real and most true (see Fig. 8).

References

Aunger R. 2007a. Major Transitions in ‘Big’ History. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 74: 1137–1163.

Aunger R. 2007b. A Rigorous Periodization of ‘Big’ History.

Technological Forecas-

ting and Social Change 74: 1164–1178.

Baker D. 2013. 1050. The Darwinian Algorithm and a

Possible Candidate for a ‘Unifying Theme’ of Big History. Evolution: Development within Big History, Evolutio-

nary and World-System Paradigms / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, and A. V. Korotayev, pp. 235–248. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Barrat J. 2013. Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Barry P. 2017. Narratology. Beginning Theory: An Introduction to Literary and Cultural Theory. Manchester University Press.

Barth K. 2003. God Here and Now. London: Routledge.

Blanks D. 2016. A Psychoanalysis of Big History. Third IBHA Conference: Building Big History: Research and Teaching (14–17 July, University of Amsterdam).

Bostrom N. 2014. Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chaisson E. 2011a. Cosmic Evolution

– More Than Big History by Another Name. Evolution:

A Big History Perspective / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, A. V. Korotayev, and

B. H. Rodrigue. Volgograd: ‘Uchitel’ Publishing House.

Chaisson E. 2011b. Energy Rate Density as a Complexity Metric and Evolutionary Driver. Complexity 16(3): 27–40.

Chaisson E. 2014. The Natural Science Underlying Big History. The Scientific World Journal. DOI: 10.1155/2014/384912.

Christian D. 2004. Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Christian D. 2008. Big History: The Big Bang, Life on Earth, and the Rise of Humanity. Chantilly, VA: The Teaching Company.

Christian D. 2017. What is Big History? Journal of Big History 1(1): 4–19.

Christian D., Brown C., and Benjamin C. 2011. Big History: Between Nothing and Everything. New York, NY: McGill-Hill Education.

Davis W. 2009. The Wayfinders: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters in the Modern World. Toronto: House of Anasi.

Deacon T. 2011. Incomplete Nature: How Mind Emerged from Matter. New York: W.W. Norton.

Delahaye J. P., and Vidal C. 2016. Organized Complexity: Is Big History a Big Computation? arXiv preprint, arXiv: 1609.07111.

Dennett D. 2014. The Self as the Center of Narrative Gravity. Self and Consciousness / Ed. by F. S. Kessel, P. M. Cole, D. L. Johnson, and M. D. Hakel, pp. 111–123. Psychology Press.

Derrida J. 1997. Deconstruction in a Nutshell: A Conversation with Jacques Derrida (No. 1). Fordham University Press.

DeWitt B. S., and Graham N. (Eds.) 2015. The Many Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Dieter H. 2008. Between Kant and Hegel. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Drees W. B. 1990. Beyond the Big Bang: Quantum Cosmologies and God. Open Court Publishing.

Evans D. 2006. An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis. London: Routledge.

Foucault M. 1972. Archaeology of Knowledge. New York: Routledge.

Foucault M. 1980. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977. Pantheon.

Friedman T. 2005. The World is Flat. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Frolov V. P., and Zelnikov A. 2011. An Introduction to Black Hole Physics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goertzel B., and Goertzel T. (Eds.) 2015. The End of the Beginning: Life, Society, and Economy on the Brink of Singularity. San Jose: Humanity + Press.

Goldstein H. 2011. Classical Mechanics. Pearson Education.

Heidegger M. 1988. The Basic Problems of Phenomenology. Vol. 478. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Hegel G. W. F. 1998. Phenomenology of Spirit. Transl.

by A. V. Miller and J. N. Find-

lay. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.

Heylighen F. 2011. Self-organization of Complex, Intelligent Systems: An Action Ontology for Transdisciplinary Integration. Integral Review 1–39.

Heylighen F. 2014. Complexity and Evolution: Fundamental Concepts of a New Scientific Worldview. Lecture notes 2014–15. URL: http://pespmc1.vub.ac.be/books/ Complexity-Evolution.pdf.

Hofkirchner W. 2017. Imagined Futures Gone Astray: An Ontological Analysis. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute Proceedings 1.

Hofstadter D. R. 2007. I am a Strange Loop. New York: Basic Books.

Jameson F. 2013. The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act. London – New York: Routledge.

Kaku M. 2014. The Future of the Mind: The Scientific Quest to Understand and Empower the Mind. New York: Anchor Books.

Katerberg W. 2018. Is Big History a Movement Culture? Journal of Big History 2(1): 63–72.

Kauffman S. 2010. Reinventing the Sacred: A New View of Science, Reason, and Religion. New York: Basic Books.

Kojève A. 1980. Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit. Cornell University Press.

Kripal J. 2007. Esalen: America and the Religion of No Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kuhn T. 1962. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kurzweil R. 2001. The Law of Accelerating Returns. Kurzweil AI: 1–146.

Kurzweil R. 2005. The Singularity is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology. New York: Penguin.

Last C. 2017a. Big Historical Foundations for Deep Future Speculations: Cosmic Evolution, Atechnogenesis, and Technocultural Civilization. Foundations of Science 22(1): 39–124. DOI: 10.1007/s10699-015-9434-y.

Last C. 2017b. Global Commons in the Global Brain. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 114: 48–64. DOI: 10.1016/j.techfore.2016.06.013.

Last C. 2018. Cosmic Evolutionary Philosophy and a Dialectical Approach to Technological Singularity. Information 9(4): 78. DOI: 10.3390/info9040078.

Lloyd S. 2006. Programming the Universe: A Quantum Computer Scientist Takes on the Cosmos. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Luisi P. L. 2016. The Emergence of Life: From Chemical Origins to Synthetic Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lukács Ge. and Lukács Gy. 1971. History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics. Vol. 215. MIT Press.

Lyotard J.-F. 1984. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Maturana H. R., and Varela F. J. 1991. Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living. Vol. 42. Springer Science & Business Media.

Metzinger T. 2004. Being No One: The Self-Model Theory of Subjectivity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Nietzsche F. 1883. Thus Spoke Zarathustra. The Portable Nietzsche / Ed. by W. Kaufmann. New York: Viking Press.

Penrose R. 2004. The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Peterson J. B. 1999. Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief. Florence, KY: Taylor & Frances/Routledge.

Plato. 1998. The Dialogues of Plato: Volume II: The Symposium; Transl. with Comment by R. E Allen. London: Yale University Press.

Ricoeur P. 2010. Time and Narrative. Vol. 3. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Rodrigue B., Grinin L., and Korotayev A. (Eds.) 2012. From Big Bang to Global Civilization: A Big History Anthology. Oakland: University of California Press.

Rose H., and Rose S. 2010. Alas Poor Darwin: Arguments Against Evolutionary Psychology. London: Random House.

Simon R. B. et al. 2015. Threshold 9? Teaching Possible Futures. Teaching Big History / Ed. by R. B. Simon, M. Behmand, and T. Burke, pp. 232–260. California: University of California Press.

Sloterdijk P. 2011. Bubbles: Microspherology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Smart J. 2008. Evo Devo Universe? A Framework for Speculations on Cosmic Culture. Cosmos and Culture: Cultural Evolution in a Cosmic Context / Ed. by S. J. Dick and M. L. Lupisella. Govt. Printing Office, NASA SP-2009-4802.

Smolin L. 2001. Three Roads to Quantum Gravity. New York: Basic Books.

Snow C. P. 1959. Two Cultures. Science 130, 419. DOI: 10.1126/science.130.3373.419.

Sokal A. D. 1996. Transgressing the Boundaries: Toward a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity. Social Text 46(47): 217–252.

Spier F. 2005. How Big History Works: Energy Flows and the Rise and Demise of Complexity. Social Evolution & History 4: 87–135.

Spier F. 2010. Big History and the Future of Humanity. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Spier F. 2017. On the Pursuit of Academic Research Across All the Disciplines. Journal of Big History 1(1): 20–39.

Sternberg M. 1987. The Poetics of Biblical Narrative: Literature and the Drama of Reading. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Teilhard de Chardin P. 1955. The Phenomenon of Man. New York: Harper & Row.

Thompson E. 2010. Mind in Life: Biology, Phenomenology, and the Sciences of Mind. Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

Vidal C. 2014. The Beginning and the End: The Meaning of Life in a Cosmological Perspective. Berlin: Springer.

Vinge V. 1993. The Coming Technological Singularity. Whole Earth Review 81: 88–95.

Voros J. 2013. Profiling

‘Threshold 9’: Using Big History as a Framework for Thinking about the Contours

of the Coming Global Future. Evolution:

Development within Big History, Evolutionary and World-System Paradigms /

Ed. by L. E. Grinin, and

A. V. Korotayev, pp. 119–142. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Wallace D. 2012. The Emergent Multiverse: Quantum Theory According to the Everett Interpretation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilson E. O. 1998. Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. New York: Random House.

Žižek S. 2012. Introduction. Eppur Si Muove. Less than Nothing: Hegel and the Shadow of Dialectical Materialism. London: Verso.