Technological Achievements of the Future as the Path of Destruction of Habitual Human Society?

Almanac: History & Mathematics:Investigating Past and Future

Assuming that extensive experiments on the correction of the human genome will fall on the 2030s and 2040s, the author comes to the conclusion that the real problems associated with the emergence of new subspecies of Homo sapiens will arise already in the 2070–2080s or even in the 2060s. Although such prospects are usually considered in an apocalyptic manner, the tragic course of events is not necessary. But, in any case, there will arise new unprecedented problems, primarily inequality problems, not only socio-economic but legal and political ones, as well as generally the possibilities of democracy in a society of genetically different people, etc.

Keywords: human society, scientific forecasting, liberal democracy.

Introduction. Is a Scientific Forecasting Possible?

The very possibility of forecasting the future has long been a problem that worried all people. In the era of universal belief in God the main problem was human's free will; as the social consciousness secularizes, the center of gravity is shifting to the issue of the existence or non-existence of laws of history that make it possible to predict. It is very difficult for a modern person, especially for a free-thinking and involved in the scientific community person, to make a choice between alternatives. On the one hand, he wants to have freedom of will, even if limited not only by physical laws but also by social ones; in any case, freedom should be so great that a historical forecast would be impossible. This point of view is most consistently argued in K. Popper's book The Poverty of Historicism (Popper 1957). On the other hand, for the thought that some aspect of reality, or rather, not some aspect but the very future of humanity, is beyond the scope of scientific analysis, is absolutely alien.

Synergetics or nonlinear science first made it possible to answer this question in agreement with both attitudes. According to E. N. Knyazeva and S. P. Kurdyumov,

The future is open and not singular, but it is not arbitrary. There is a limited set of possibilities for future development; for every complex system there is a discrete spectrum of structure-attractors of its evolution. This spectrum is determined solely by its own properties. In nonlinear situations of instability and branching of evolutionary paths a human plays a decisive role in choosing the most favorable (and at the same time feasible in this environment) future structure, one from the spectrum of possible structure-attractors. Because of the inevitable elements of chaos, fluctuations and the presence of strange attractors, there are certain limits to our penetration into the future there is a horizon of our vision of the future. At the same time, the synergistic approach allows us to see the real features of a future organization by analyzing today's spatial configurations of complex structures arising in a certain type of fast evolutionary regimes (Knyazeva and Kurdyumov 2001: 5).

However, the declaration of such a promising approach did not give rise to a real methodology for its application. Many economic and social indicators do not have unambiguous numerical values; there are no ways to isolate a discrete spectrum of attractor structures, or, more precisely, every scientist when engaging with futurology creates his own spectrum of attractor structures himself and he selects alternatives within it. Some scientists rely on competition between the United States and China or global debt growth, some on the development of artificial intelligence, others on global warming and different environmental problems, etc. Therefore, understanding the inaccessibility of a purely scientific approach (which is the reason why scientists try to avoid answering the questions that politicians and amateurs most often ask them), let us approach the problem of forecasting the future from more practical positions and pay attention to the elementary, at first glance, question: how to approach the preparation of the forecast.

Unfortunately, I cannot give a reasonable answer to this question which would be convincing for any skeptic opponent. Therefore, in this section of the chapter, the thesis that the initial stage of the forecast, which constitutes at least half of all the work, consists in determining to which field of knowledge this question belongs and, accordingly, by which methods it should be solved, is adopted as an admission. It may seem that I am talking about finding the main trend that determines the future. Of course, in many cases this is the case, but in principle we are talking about more – it is necessary to determine which methods, from which field of knowledge, are most suitable for finding this basic trend (reducing the pathos of the statement, I will note that tomorrow these methods may change).

How Far Ahead Can We Predict?

In this section I want to express a rather controversial idea that there is a segment of the future which is most accessible for forecasting and limited from above and below.

The presence of restrictions from above does not cause any special doubts. If you do not take into account the obvious (for today's science, tomorrow they can be challenged!) restrictions, for example, all people are mortal, mineral resources are limited, over the next tens of thousands / hundreds of thousands / millions of years there will be a supervolcano eruption, a new glaciation, inversion of magnetic poles, etc., the distant future is not available for forecasting. Within the constraints of K. Popper (for more details see Rozov 1995), we cannot go beyond the current trends (and their projected modifications) and, moreover, cover the time in which scientific discoveries and inventions, not made and not expected today, will play an important practical role. The more these trends, discoveries and inventions determine the content of the future epoch, the less one can say about it at present.

The presence of a lower boundary is less obvious. It is quite clear that the very next moment is best predicted the next hour, tomorrow. The best forecast is an extrapolation of well-known (most often linear) trends for steadily changing objects, and the existing state (value) is for all others, that is few and/or unstable changing processes. However, such a trivial forecast is of no value and is not considered as a forecast. The consumer of the forecast wants to know what is going to happen, what might go wrong, what will occur or not occur tomorrow, the closer the predicted time – the more accurately.

My statement about the presence of the lower boundary lies not in the fact that the more distant future can be predicted more accurately than tomorrow, but that the ratio forecast error v. deviation allowed by us decreases with the increase of the distance from the present day. Just as we (of course, with the availability of money or an affordable loan) compare goods and services not in price but in terms of price / quality ratio.

Accordingly, the scale of poorly predicted events decreases when approaching the present moment more slowly than the allowable (expected) deviations from the trivial forecast. Similar phenomena are known for stock price fluctuations (Mandelbrot et al. 1997; Peters 2003).

Mathematically, they can be understood as a fractal character (or non-integer dimension) of the process. In fact, here we are talking about monthly, weekly and daily news in the media, including quite large-scale and unexpected and, naturally, not predicted by any of the analysts. The sources of such events are diverse, they include accidental occurrences of natural and man-made origin, (including diseases and death of leading world politicians), quick transitions of hidden unobtrusive processes to an explicit stage, unexpectedly early manifestations of predicted distant processes, etc. Note that a similar statement regarding economic and financial processes has already been expressed by the 2013 Nobel Prize winner in economics Robert Schiller (2000).

The average most accessible stage for forecasting naturally has a different duration for different historical times and processes. For global phenomena, as we believe, it begins in a few years (for definiteness, let it be 5–10 years) and ends in one or two generations (for definiteness, 30–60 years).

The Complexity and Details of the Forecast

It is clear that the future as well as the present and the past will be determined by the combination of different trends. However, in our opinion, it does not make sense to take into account (or fully take into account) more than one or two, maximum three, phenomena in the forecast. First of all, because the probability of guessing all the major trends is extremely small, with an increase in the number of processes taken into account and the construction of multifactor scenarios, there is a high risk of making a mistake in at least one of the selected factors and distort the predicted future. It is more important to predict at least the main contours than to furnish and decorate them with dubious details.

Now, after a prolonged introduction, let us proceed to the forecast itself or, more precisely, to the choice of those areas of knowledge and the main trends on which the forecast will be built.

What Has Happened to Liberal Democracy?

The number of books and articles on crisis, decay and the end of Western democracy is already very large and continues to grow. As examples of the alarm that Western liberals and democrats declare, I will mention some well-known books (Runciman 2018; Mair 2013; Levitsky and Ziblatt 2018; MacLean 2017; Tooze 2018; Rosenfeld 2019; etc.), but this enumeration is only a tiny part of a huge and growing list. Moreover, the alarm that the authors of these and other books declare is not the speculations of alarmists, but real fears based on facts. The political systems of the leading Western countries with a long history of democracy are crumbling, parties with a long history and a well-established circle of supporters give way to new populists, who proclaim sonorous slogans that they are unable to implement. The European Union, which in the past had only recruited new members, is now beginning, or has already begun, to decline in number and, moreover, in the eyes of many has turned from the quintessence of the European spirit into a bureaucratic structure that is stifling traditional Europe. Liberal democracy itself loses its attractiveness, and many Western leaders sometimes use transparent hints or quite openly, as the Hungarian leader V. Orban, oppose liberal democracy to a non-liberal, populist one, which ignores the minorities' views.

So what is the reason for these changes, which occurred even before the main transformations that will be discussed in this chapter?

First of all, we emphasize once again that the system we call democracy is not democracy at all, but rather liberal democracy. The word ‘liberalism’ is extre-mely polysemantic and every day acquires more and more different, sometimes contradictory, meanings. In this chapter liberalism refers to various rights of people, ideally not subject to revision by popular vote – the right to life, freedom from torture and extrajudicial punishments, the right to own property, equality of people before the law common to all, freedom of speech, freedom of conscience, etc. Of course, in fact, this list has changed many times and continues to change. The main thing is that all these diverse rights and freedoms limit democratic expression of will (in practice, of course, it looks different – the results of votes and their interpretations by honest and dishonest politicians limit or expand the list and determine the forms of realization of rights and freedoms).

This description of liberal democracy is extremely simplified; in order to bring it closer to reality, it is necessary to add not only representation instead of direct democracy, the presence of a management apparatus, a market economy, the power of money and corruption, but also a social state, globalization, weak and contradictory international law, etc. However, in order not to obscure the main issue with additional entities, we will roughly and straightforwardly attribute the social state to democracy, and globalization and international law to liberalism. Obviously, this is a very clumsy truncation of the number of entities; for example, in the United States it would be more reasonable to attribute most of the social state to liberalism and not to democracy.

But for us something else is more important: how this compromise between democracy and liberalism could exist and be perceived for so long by the majority from the most illiterate and naive voter to the knowledgeable political analyst, as the best order that should only be maintained, carefully improved and distributed over the whole world. After all, we remember that the formation of liberal democracy in the second half of the 19th – early 20th century ended with a complete loss of nationalism and with a world war and in the period between world wars liberal democracy in most countries did not recover. Some successes in the field of social guarantees and even liberal freedoms (e.g., the electoral rights of the poor and women) were more likely to work against liberal democracy than for it.

It was only in the fifties or even in the early sixties, after a prolonged period of post-war development, the time of active introduction of communists into the governments of Western countries and anti-liberal McCarthyism opposed to them, that liberal democracy for many years became the only alternative system. Why then was it that not only the repulsion of liberal democracy, but even doubts about it faded into the background? Making up a long list of reasons, one should mention the horror of the Holocaust, the rejection of Stalinism, the destruction of the traditional society with its traditional gender and racial discrimination, the growth of social guarantees, etc. But all this can be expressed in a few words; people saw their life getting better, and they believed that liberal democracy was the basis of these improvements in the present and a guarantee of continuation in the future, both in the area of material well-being and comfort and in ensuring their rights and freedoms.

Now this belief is blurring or coming to an end. Why?

In order to identify the culprits of growing distrust of liberal democracy in the present, we first have to try and take a look into the recent past.

Starting with the Industrial Revolution of the turn of the 18th – the 19th centuries, or even of the earlier agricultural revolution, at first only the Western society, and then the whole world, lived in an environment of frequent, sometimes overlapping, big and small technological revolutions. All these revolutions destroyed the old occupations of people, replaced them with more productive work with new equipment and new technologies, but at the same time immediately, or with some time lag, very difficult for the poor and unemployed, created new occupations which, as a rule, required more knowledge, more attention and accuracy.

The destructive side of the ongoing and beginning economic changes (among them we note not the most important, but a very relevant one, the reduction of customs duties and ease of international financial transactions) and technological revolutions, which will be discussed further, manifested primarily in the mass migration of industrial employment from the first world to the third, primarily to China, as well as the beginning of economy robotization (see below).

However, robotization of economy is just beginning, and we will consider its consequences below, whereas the transfer of the manufacturing to China and other third world countries has been going on for quite a while, since the time when illusions related to liberal democracy, the future of the European Union and the entire Western world, have flourished. Thus, disappointment in liberal democracy and its destruction began seemingly at the wrong time, in one (retroactively invented) version too late, and in the other – too early.

But this impression is deceptive. Automation and transfer of the traded sector, industrial production to the third world countries in the first place, sharply reduced the number and incomes of the middle stratum of employees especially of its central part and number of people engaged in technically difficult physical labor. Following them, employment and incomes of service workers and white-collar workers with routine duties began to decline. A significant part of the remnants of the former splendor of the middle class, which includes both physical and mental labor, has turned into poorly paid labor, which only the strongly overgrown strata of migrants from poor countries are ready to perform.

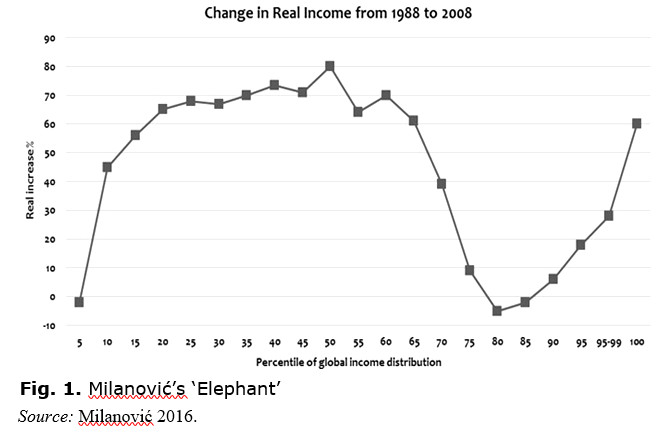

As a result, instead of the previous concentration around the middle class occupations, engineering and physical labor at large factories and average earnings, the labor market became polarized and stratified. On the one hand, there are masses of low-paid workers, often with short-term contracts, and on the other, there is a far from numerous number of entrepreneurs, managers and professionals whose incomes have increased many times over. The now famous Milanović's ‘Elephant’ (see Fig. 1) clearly shows that the workers and the middle class of Western countries turned out to be the main losers (or rather, non-winners because their incomes remained at the level of the 1970s – the 1980s, rather than reduced) as a result of the economic and political changes of the last decades. At the same time, all social benefits have not vanished; on the contrary, new ones were added, making the budgets of developed countries increasingly deficit, even the introduction of universal benefits is mentioned, but it is impossible to cover the original income inequality and, even less, the uncertainty about tomorrow.

First, the unreliable world, where the future, tomorrow's orders, tomorrow's work and tomorrow's earnings are even more unreliable than today's, makes people reject the liberals who are leading them into this quagmire, makes them believe in conspiracy theorists, fake news, promises of populists and nationalists. It forces people to oppose violation of traditions, strangers, globalization, international law, etc.

Secondly, the blame for the ideological consequences of socio-economic changes and globalization should not be put exclusively on populists. Every single left-wing and mainstream politician opposing them turned out to be completely unprepared for the destruction of the usual picture of the world and the usual perspectives. There are a great many of them increasingly paying no regard to the problems of the majority, directing their efforts to provide various benefits to formerly discriminated groups of the population, migrants, and more and more exotic sexual minorities. Surprisingly enough, caring so much about various minorities and the equality of opportunities, they themselves began to turn into a closed community which mainly includes only the elite people, members of families who have been in power for a long time or near it and graduates of elite universities imbued with a left-wing, social democratic and simply socialist ideas.

Therefore, somewhat exaggeratingly, it can be said that not only democracy, turning into populism, played false liberalism, but liberalism, turning into a struggle for positive discrimination, played false democracy and even itself, its own principle of equality of all before the law. Unfortunately, if we add to this the very widespread corruption of mainstream politicians, their connection with big business (populists are easily forgiven such things, and even worse ones), then the blame can really be laid on both sides.

Populism, a political trend that is very often diminished, as a rule, with negative connotations, but each political scientist gives his own definition of populism or completely dispenses with definitions believing that without definition everyone understands what is at stake, became the leading political trend that supplants mainstream conservatives, liberals and social democrats.

Based on the works of the third-party Russian observers (Makarenko and Petrov 2018; Zotin 2019), I will try to formulate my vision of populism.

1. At first glance, the main feature of populists is their ‘anti-elitism’, but in fact it is rather a slogan that helps push the representatives of the old elites from the political Olympus than a clear characterization of populism. Despite the passion of the populist accusations of the elite, anti-elitism of the populists remains rather vague; the really egalitarian movements of the opponents of the current elite, who consider it rotten, corrupt and worthless, as well as representatives of the ‘second rows’ of the old elite, who are looking for other ways to achieve power, can be distinctly anti-elite. In addition, populist anti-elitism does not prevent referring to famous former members of the elite (e.g., starting from Bolivar), or seeking to take the places of the current elite themselves, and moreover, to have representatives of the former elites and not the most exemplary ones among their leaders. It is unlikely that the anti-elitist Trump, who is habitually called populist, is really better and ‘cleaner’ than the old Washington elites. In other words, it is not important that anti-elitists are present in political life (as they have been from former times), but that their anti-elitist speeches of various kinds have a wide response.

2. The second feature of populism according to Mudde and Kaltwasser (2017) is the Manichaean ideology which divides the ‘right’ people supporting this populist and the ‘wrong’ people supporting the old corrupt elite, and therefore, not any people at all in the full sense of the word. In other words, this division destroys the liberal rules for the protection of rights and the consideration of minority opinions, which can become the majority in the next elections. In another version (Makarenko and Petrov 2018) the second feature of populism is ‘plebiscitarity’, which includes both inattention to existing institutions and inattention to the opinion of the minority who had lost the plebiscite. Descending to the very pragmatic level of describing the organization of state power, it can be said that populists ignore the complex system of checks and balances between branches of government that prevents the transformation of democracy into a dictatorship.

However, it is not that simple; left-wing advocates of the rights of women, national, racial and sexual minorities also treat their opponents with contempt and, being in the majority, no less scornfully regard the opinions of their opponents, calling them fascists, sexists, racists, trash, etc. In this sense, left-wing fighters against populism differ little from their opponents. Although in the political life of Western countries violence until recently played an ever diminishing role, the very highlighting of Manichean ideologies may mean the beginning of a reverse tendency. In any case, a comparison of today's ‘Gilets jaunes’ (yellow vests) with the recent ‘occupy’ is quite obvious.

3. The third feature, according to A. Zotin (2019), is to push the boundaries of the politically possible, for example the encroachment of Gilets jaunes on the fight against global warming. According to Makarenko and Petrov (2018), the third most important aspect of populism is ‘the problem with the responsibility of power and control over it’. But connecting their opinions together we understand that it is a question of something greater, – readiness for refusal or even rejection of liberal restrictions itself, – freedom of speech, freedom of conscience, equality of people before the law that is common to all, etc.

Here it is necessary to touch upon the relationship between populism and democracy. According to its slogans, modern populism contributes to the inclusive development of democracy, unlike populism in the 1920–30s, when populism quickly passed into dictatorship or even from the very beginning had combined with the cult of the leader. Indeed, populists are not so ready to go beyond liberal democracy, like their predecessors in the 20th century. However, the Hungarian and Polish examples show that the difference between the attitude to democracy between the prewar and modern populist movements is primarily due to external circumstances formed over the past decades and for the time being existing normative standard of the democratic way of legitimizing the authorities. Therefore, the transition of populist movements from pointed democracy to outright struggle with democratic institutions does not take place immediately but takes years, maybe even 10–15 years (as, e.g. in present-day Venezuela), but the path itself from ‘ochlocracy to despotism’ changing many forms, has retained its essence since the time of Aristotle.

4. The fourth and ‘probably the most important feature of populism’, according to A. Zotin (2019), is ‘operating with the resentment feelings of voters’, to which we can add the inattention of the populists to the opinions of experts, except for the group they choose which usually includes conspirologists with unverifiable assertions.

These resentment moods are quite different – from anecdotal (but nevertheless real):

– when the sky was blue and the grass was green;

– when men were courageous and women were virtuous, to various social ones:

– when trade unions defended workers and the rich paid 80–90 % tax;

– when men were breadwinners and women kept the house and raised children;

– when marriage was possible only between men and women;

– when gays and lesbians hid in dark corners and did not come out into the streets and squares, but still, most of the populist resentment wishes are in one way or another connected with national relations, and the new nationalism is not as aggressive as the former, is mainly defensive in nature and is in the first place turned to the country, and not outside, like classic offensive nationalism;

– when foreign goods did not compete with ours;

– when migrants did not take away our jobs;

– when our taxes were not used for the maintenance of migrant idlers;

– when there were no districts which the native inhabitant of the country was scared to enter;

– when minarets and muezzins did not violate the appearance and peace of my country, at the same time, many resentment attitudes are in the nature of overt xenophobia (behind the deliberate political correctness of books, feature films, university courses, business rules, there is a clear disunity among the representatives of different races, migrants and the ‘indigenous’ population, the rarity of inter-ethnic, inter-religious and interracial marriages);

– when my country was my country, and not a through passage for different foreigners;

– when political correctness did not interfere with calling kikes ‘kikes’ and niggers ‘niggers’;

– when there were not so many people of different races dressed in strange clothes walking in the streets.

At the same time, the fight against xenophobia may be xenophobic in nature. In Western European countries, especially in England and France, left-wing anti-Semitism is growing, less and less hidden behind the condemnation of Israel's policies on the occupied territories, unlike Eastern Europe where right-wing anti-Semitism continues to prevail also becoming more widespread especially in Hungary and Poland.

Dissatisfaction is also manifested on the part of migrants and foreign minorities who are not assimilated or even, on the contrary, are moving away from the ethnic majority (titular) nation. For some migrants, the Western reality seems so godless and immoral that it provokes extremist sentiments and even Islamist attacks; some are dissatisfied with their second-class status, their belonging to the poor part of society; others believe that positive discrimination is not enough and does not block the negative impact of hidden racism that prevents them from entering the big world.

However, it is not necessary to see in the resentment moods only the fight against progress, xenophobia, racism, etc. People tend to consider the course of life from the time of their youth as the only true one; people are tired of the global nature of the modern world that is breaking their habits and customs. And although modern left-wing liberal leaders strongly oppose manifestations of localism and see only sexism and xenophobia in traditionalism, the original principles of liberal democracies do not forbid anyone to have their own views and their own ideas of happiness.

Of course, these and other types of sometimes rough and even bloody discontent existed before the 2008 crisis. In the nineties and zero years there was genocide in Rwanda, a long war in the former Yugoslavia, the event of 9/11, the US invasion of Iraq, mass discontent with neoliberalism and IMF policies, corruption scandals, rising income inequality, etc., but nonetheless it seemed to many, if not to the majority, that the world is getting better, that the difficulties of growth will be overcome, that globalization improves the lives of a huge number of people and brings humanity closer together, etc.

After the crisis of 2008–2009 and its second wave in Europe, accelerated growth of inequality and rising unemployment (often hidden from statistical reports) in Western countries, the Arab spring which raised great expectations but developed into large-scale wars in the Muslim world, the growing conflict between Russia and the Western world, the end of democratization of China, etc. historical optimism was replaced by historical pessimism; liberal democracy cracked simultaneously in many old and new democracies. To many people globalization was then seen not as good, but as evil, migrants as enemies, technological progress with the threat of further deterioration of the working class and middle classes, and resentment nationalist feelings captured millions of people.

Thus, popular Russian questions ‘Who is to blame?’ and ‘What is to be done?’ were set before the Western society. As is usually the case, there is no clear answer to the question ‘What is to be done?’ And to the question ‘Who is to blame?’ the most popular answer, supported by many voters (and in some countries by the majority which rejected the traditional parties as well), is ‘Our corrupt and talentless elites’; they are accused of:

– increased corruption (partly due to simplified transnational transactions and facilitating the process of tying up loose ends);

– the increased dependence of deputies and ministers on party bureaucrats, political consultants and party sponsors (the ‘deep state’ in terms of conspiracy theories);

– focusing on international issues and interaction with international globalist organizations while neglecting national traditions and domestic issues;

– excessive attention to the problems of various minorities, migrants, the introduction of multiculturalism while not paying attention to the majority working at factories, farms, in offices, shops and receiving a decreasing part of the common pie.

There is a fair amount of truth in all these accusations. However, I do not think that the growing problems of the present world are rooted in the fact that the elites have become so much worse. Schröder or Berlusconi ruled in the most optimistic times, and Merkel or Macron (despite the too hasty and unsuccessful course of the reforms) clearly do not belong to the worst leaders of the Western world.

The main fault of the elites is that they did not foresee, and, having seen, did not recognize the problems that the globalization of the economy and financial markets, the growth of inequality, the transfer of manufacturing to the third world, automation and robotization, the economic growth of China and other third world countries, reformation in the Muslim world, increasing migration, etc. are bringing about. Already faced with the problems, they did not find solutions and were powerless in front of populists, offering simple and lashing answers to insoluble questions.

Moreover, left-wing liberal in name (and in fact left-wing, but not liberal) politicians, especially from the US Democratic Party, made special efforts to protect previously discriminated groups and various minorities. For some reason, the simple idea that people's self-perception is determined not only and not so much by the discrimination of their predecessors and even their own position today but by the dynamics of their changes, turned out to be alien to them. As a result, maximum frustration, maximum dissatisfaction with life became the lot of white-collars and blue-collars in rich countries, very prosperous on a global scale (the neck of Milanovic's elephant) and generally not the poorest in their countries but descending down the social scale. The most offended turned out to be heterosexual white men with secondary education, the target for the attacks of the ‘voices of progress’. Moreover, these seemingly evaluative statements have quite visible confirmations (Case and Deaton 2015) – approximately in the middle of the 1970s, blue-collar incomes stopped growing in the United States, and since the end of the 1990s not only did the growth of life expectancy for whites without higher education stop but there began an increase in their mortality rate. Nevertheless, the American democrats ignore rising mortality and falling incomes, but discuss the issue of paying reparations to African Americans for the sufferings of their great-great-grandfathers. Moreover, the opponents of populism are not embarrassed by the fact that they are moving further and further away from liberal principles: freedom of speech, equality of all before the law, presumption of innocence and the restrictions imposed by left-wing liberal progressists are often introduced not in the form of Western law but in the form of the Russian ukaz (decree), addressed only to a certain group of the population (men, white people, heterosexuals, etc.), change their severity over time and are more often used not by the court but by administrations of state companies and organizations of private ones. And although left-wing liberal politicians distinguish the most patronized citizens from among the most miserable, in their opinion, segments of the population: the Chinese government chooses from those that are the most loyal, Islamists from the most orthodox and fanatical, and populists from the most traditionalist layers. I see a certain generality in this neglect of a liberal understanding of human rights.

So the Western world on the eve of important technological changes that destroy the traditional society is in a bad condition. The failed triumph of the populists in the elections to the European Parliament in 2019 should hardly reassure defenders of liberal democracy; it rather showed the inability of populists to offer effective solutions to contemporary problems than the ability of liberals and social democrats to meet the challenges of their time.

At first glance, non-democratic and semi-democratic countries, especially China, as well as India, Russia and the Muslim world feel much better and are more prepared for a new world. However, it seems to me that this is to a great extent not a prediction but an illusion, a ‘horror story’ of the Western world. Yes, of course, nondemocratic countries, especially China, are much more willing to apply the achievements of electronics, mathematics and genetics to retain power, suppress dissent, economic exploitation, etc., but their inflexibility is unlikely to allow them flourish in a world that is extremely indebted to itself and, most importantly, in which very soon there will be a lack of work, what precisely pulled them out of poverty and made it possible to catch up with and overtake the western countries.

Technical Progress and Changes in the Global Division of Labor as Two Main Factors for the Growth of the Transformation of the Labor Market and the Growth of Inequality within Western Countries

Perhaps, the most basic today's socio-economic processes are the changes related to inequality. The convergence of the economic level (primarily in terms of GDP per capita) of the West and the East, the first and the third world is accompanied by an increase in social inequality within countries, covering most of the third world countries, Russia (a fragment of the second world) and almost all western countries (although in varying degrees).

In other words, we can state the degradation of social states, if we understand them not as a characteristic of the share of public expenditures for social needs, but as a form of society organization. At the same time, of course, one can argue for a long time about whether it is appropriate to call a social structure without private property, market and democracy a social state, i.e. whether the USSR and other socialist countries can be considered social states. However, the existence of similar features and interdependent history in the creation of social states of the West and the humanization of the post-Stalinist Soviet system will not be challenged.

As it is known, in the end, the former triumph of social equality in the USSR, turned into a sharp social stratification in the 1990s, mass unemployment and the destruction of many forms of social protection for the poor including those that during the 20th century were not perceived as social achievements but as inalienable rights of the citizens. Around the same years, but quite differently, the degradation of social states in the West took place. Contrary to popular belief during the years of rampant ‘Thatcherism’ and ‘Reaganomics’ there was no significant decrease in the share of government expenditures in GDP (and in particular, social expenditures). The reduction of social expenditures in the composition of GDP, about which there was so much written, amounted to 3–5 % – 15–20 % in different countries.

The mass automation and robotization predicted by E. Toffler (1980) and other sociologists and futurologists did not happen in the 1980–90s. Nevertheless, the total number of working class of Western countries and their earnings really stopped growing in the 1970s and even began to decline.

The main process, contrary to all predictions, was the growing transfer of industrial production to the third world countries. It must be said that the idea of using the cheapest labor played an important role from the very beginning of the existence of capitalism and it took various forms. From the 17th to the first half of the 19th century there was the massive use of female and child labor, as well as the organization of home-based production in the poorest and most land-hungry villages. The most severe form of such exploitation was slavery, the decline of which began with bans on bringing new slaves into and out of the country (1823, 1834, the 1840s, etc.) and the abolition of slavery in the southern states of the US (1863). However, even after the ban on slavery in the United States, in many colonies in Africa and the Caribbean certain forms of slavery persisted for a long time, although they did not have such an impact on the world economy.

However, the attempts to find other ways of searching for cheap labor continued. One such attempt was the transfer of enterprises to very poor colonial and semi-colonial countries. G. Clark in his book A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic very clearly describes the factory in Bombay (Clark 2007). Extremely poor organization of work, very low qualifications of workers and the high cost of transporting goods more than covered all the additional profits from the 12-hour working day and very low wages.

Since the days of Ford's factories, first in the USA and then in other Western countries, an 8-hour period of intensive work of competent, skilled and well-paid workers has become the standard. Further gains of the working class, partly occurring under the influence of Soviet propaganda and fear of social upheaval including annual vacation, full or partial payment for working days, missed due to illness, trade union protection, unemployment benefits, etc., further raised labor costs but did not reduce the growth rates of the economies of Western countries. On the contrary, the 1950s and 1960s were the years of the fastest growing industry in western countries and in the world as a whole.

Why did the idyll of social states in the early 1970s crack, and from the late 1970s began the process of de-industrialization of Western countries? There are many mutually exclusive and even more complementary answers to these questions. I will dwell only on those things that seem to me the most important.

The indisputable reasons for the growing success and scale of industrial projects in the third world countries were the increasing literacy of their people and especially the changing economic policy of China, the largest and most literate country with unique labor traditions and a cult of education. The development of communication facilities, first faxes, and then cell phones and email can be mentioned as the next important reason. However, it seems to me that their role was not so great and cellular communications and the Internet became widespread in the third world countries much later. And although the telefax (a new technique for transmitting the already long-existing photo-telegrams) is much more convenient than long-distance telegraph and paper letters, it did not play the main role.

More important, in my opinion, was the role of medicine, primarily of new antibiotics and drugs against the terrible Asian diseases.[1] Medical facilities along with the construction of new hotels removed the fear of engineers and managers in Asia with its terrible diseases (China's dry climate could have played a role compared to the previously available India) and allowed them to organize manufacturing facilities in Asia over long periods of time and also invite a variety of specialists if considered necessary.

Against this background, robotization and automation stepped into the sidelines and the words ‘artificial intelligence’ left the front pages of newspapers and magazines. Industrial production, including very advanced one, moved on a massive scale to China and other countries and cheap low-skilled migrants from less successful countries moved in the opposite direction and many of them went to work for lower wages to factories and plants in western countries.

Ultimately, the resulting picture in the most coarse (almost caricature) form can be formulated as follows.

In Russia, despite the fall in prices, hydrocarbons and other raw materials are the main source of income, i.e. the bulk of the country's income is generated by capital-intensive industries in which a small part of the population is employed. In the West, managers, financiers, engineers, and scientists, who also made up a small percentage of the working population, became the main earners (breadwinners). Of course, both of them are few in comparison with the army of service workers represented mainly by people with second-rate (although often higher) education and low wages.

Now let us consider robotization and automation, which receded into the background in the 1980–90s, but now are finally returning to us, reinforced by nanotechnology, superpowerful computers, 3D printers and other achievements of the technology of the 21st century.

First of all, it turned out that automatic machines and robots became able to perform not only industrial operations but also dramatically increase labor productivity in the service sector. Small pieces of paper with bar codes, pasted on each product on the shelves of stores, significantly increased the productivity of salespeople and cashiers, as well as simplified logistics of the largest and universal stores. This is probably the most effective example of the benefits of automation in the service sector, although not the only one.

In the end, the need for human labor together with the employment began to decline and income differentiation started to increase. If in the countries of continental Europe, especially in Scandinavia, with its social democratic traditions, these processes have not (yet?) led to a sharp increase in the property stratification rates, then in English-speaking countries, especially in the USA, the Gini coefficient has increased 1.5 times or more (Piketty 2014).

Thus, automation and robotization continued the process initiated by the migration of industries and the changing international division of labor. It is quite obvious (although it is not known how soon – in 3–5 years or in 10–15 years) that with further robotization of production and the service sector, the number of employees will further decrease, and the requirements for each employee, on the contrary, will increase significantly. First of all, the employee will be required to combine discipline and creativity which is widespread only in Western countries (but is currently becoming widespread in China itself and especially in Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong). Since the need for extra-class employees will be relatively small, high western wages will not be a big burden for the employer. Therefore, we can expect the return of some of the most advanced industries back to the United States, Japan and Europe.

Of course, China will fight for its position in the international division of labor retaining industrial production by all possible means: accelerated investment in the development and introduction of new technologies, mass copying of robots of previous generations, monopolization of access to raw materials, etc. A special impression was made by the statements of Terry Gow (World Robotics 2013; Bonev 2013), the head of the Taiwanese firm Foxconn, the world's largest manufacturer of microelectronics, who claimed that his company would replace part of its employees in factories in China with 1 million robots within three years, i.e. almost double the global fleet of industrial robots. At the time of the announcement Foxconn had already produced 10,000 robots and planned to increase their number to 300,000 in 2012 and to 1 million by 2014. However, the actual success in 2012 was about 20 times less than promised, while Foxbot robots themselves were evaluated by experts as cheap and fairly reliable but noticeably inferior to the best world models in their capabilities and usability. In May 2015 about 50,000 robots were involved; this is significantly more but it is the same 5 % of the promised amount. Although the level of application of robotics in China is growing at an impressive rate, it is unlikely that it will overtake more developed countries in the coming years because the salaries of yesterday's farmers are still low and robots are more needed to prove the supermodernity of production and impeccable product quality than to reduce its cost price.

The economic effect of using robots, 3D printers and automated systems is most pronounced in the countries with high labor costs. At the same time, the transfer of such highly automated enterprises to developed countries will noticeably reduce employment at the periphery and semi-periphery, but hardly increase it in the center of the World system. In both cases there will remain millions of people, not capable enough, or insufficiently educated and not in demand by the new economy. Large masses of the population, especially with low labor discipline, in developed and developing countries, will be more likely a burden for their rulers and a factor of pressure on the labor market than a factor of development. At the same time, if the emerging crisis phenomena in the Chinese economy do not take on dramatic forms, then the bulk of export-oriented production but not returning to the West will remain in China and neighboring countries.

It is the United States and other western countries that will find themselves in a very difficult situation, especially in social terms (as is clear from the ongoing political processes). But, nevertheless, it seems to me, the real economic damage that they will suffer, will not be so great despite the very unfavorable age structure of the population and various socio-political problems. Western countries have accumulated the greatest experience of effective and non-criminal provision of population employment outside the material production and the simplest forms of services, although there economic and political changes, as described above, also lead to difficult and previously not expected problems.

Two Ways to Create New System of Employment

Although the list of new occupations can be quite long, it seems that the two currently observed forms of employment which we call Russian and Western will be of primary importance. As discussed below, these names are rather conditional; the first form could also be called raw material and the second one Japanese or even traditional one but we will adhere to the chosen names.

The Russian form of artificial employment creation largely consists of activities that interfere with ordinary life and even more extensive activities to overcome these hindrances. The two main scenarios are: 1) theft and damage of material values => protection of property, houses, offices, etc.; 2) the creation of complex and inconvenient rules => activities for the implementation and circumvention of the rules. As a result, the work of a security guard has become one of the main male occupations in Russia. A significant part of Russian business consists of the firms producing various surrogates for Western and Chinese goods, and many of them are engaged only in creating unnecessary tangible and intangible objects that these enterprises require, etc.

Nevertheless, this seemingly harmful and detrimental activity is really important and even useful for the Russian economy. Its main functions are to transfer a significant part of the raw material income from a narrow circle of people directly connected with the extraction and export of raw materials to broad masses of people, as well as to multiply raw material income through expanding domestic demand and developing the non-tradable goods and services sector. In addition, the extra costs of various goods and services stimulate more intensive work of people of different professions. This has a clear resemblance to the Keynesian scattering of money from an airplane, but the source of funds is not a printing press but raw materials export. So, unlike the purely Keynesian mechanism (although in Russia the redistribution largely goes through the state budget), such activities do not cause significant harm to the financial system and do not threaten excessive inflation or a sharp decline in household incomes. Its result is economic and political stagnation, a slow decline in the standard of living of the population and the popularity of the power, but at the same time, Russia despite the aggressiveness of its foreign policy remains a quiet haven in a rapidly changing world.

Of course, all of these areas of activity, in no small part corrupt and even criminal, are characteristic not only of Russia but also of many other poorly organized raw material countries. Moreover, the growing customs barriers between western countries and the bureaucratization of public administration are expanding the scope of such activities in the richest countries with market economies, but perhaps in Russia they became widespread and acquired a rich variety of forms.

The second form, which was named Western (see above), is an already observed though not large-scale expansion of employment, an essential part of which is personal and even intimate contact between people including a physical one; that sort of employment, in which it is inherently difficult to substitute human labor or cannot be substituted by a robot at all. For example, the share of medical care in the US economy from 1960 to 2014 increased from 5 to 17.5 % (National Health Expenditures 2015).

This includes:

– medical care;

– care for the elderly, disabled and severely ill;

– parenting and childcare;

– management of physical training, cosmetology, massage, etc.;

– individual educational services;

– individual counseling on a variety of topics, for example interior design and clothing selection;

– individual and collective psychological help, including face-to-face communication (companions);

– various sexual services;

– role-playing games of various kinds.

At present, this list includes very different professions: from respectable occupations of professionals (doctors, professors, lawyers) to despicable prostitution. However, the boundaries of respectable and disrespectful activities from this list are blurred; porn models and porn actresses (like Sasha Gray) become respected members of society and professors from small provincial universities are transformed into low-paid proletariat (or even a precariat without guarantees of long-term employment and other labor protection measures). Another evidence of the commonality between these classes can be found in the films ‘The Sessions’ and ‘She's Lost Control’, the activities of the heroines of which simultaneously apply to both medicine and prostitution. In addition, there are still many other multidirectional (and significantly different from country to country) changes of places in informal tables of ranks and their relative levels of payment. It is important to note that the items in the above list are interconnected which shows once again the existence of a commonality between the classes listed. Unlike the first basic types of the Russian form of artificial employment, practically all such activities (it can be politely called as the extended ‘care work’ sphere) really satisfy human needs, from vital to exotic, and do not complicate the receiving of the same goods and services that do not require such an army of workers in more organized societies.

Social and Gender Structure of the Western Society in the Coming Decades

When describing the proposed structure of society in the near future, in addition to the rather widespread and not provoking heated debates about the role of automation and robotics, I will need very debatable statements about gender differences.

The first statement is a thesis about a smaller dispersion of intellectual abilities (IQ in the first place) of women than men with approximately equal values of averages, and accordingly, their smaller share among the most stupid and most intelligent. For the first time such statements were made by Darwin himself (Darwin 1897) and were described in detail in the article by Shields (1982). Not the only, but the most mass source on which these allegations were based, was the mass measurements of IQ and school success in Scotland in the first half of the 20th century (Hollingworth 1914; Fraiser 1919; Roberts 1945; Scottish Council 1933, 1949). There is an extensive literature that either claims that the differences in dispersion identified at that time were exaggerated, unreliable, or could not be extended to the modern period due to the fact that they were carried out in a period of pronounced inequality between women and men (Wai et al. 2010; Lubinski 2006; Hyde 2009; Hedges and Nowell 1995; Ali et al. 2009; etc.). Indeed, modern measurements indicate that in developed countries with the highest level of gender equality the differences in dispersion have decreased, although they have not yet been reduced to zero and have not lost their significance; it also turned out that there are racial differences – for example, in Mongoloids, gender differences in the dispersion of mental abilities are smaller than those of the white race, etc.

Another reason for such allegations is a higher proportion of men, both among violators of public order, criminals, the mentally retarded, suicides, etc. and among great scientists, the richest people, innovators in culture and politics, etc. Although the differences in crime rates and the number of suicides also decreased slightly with a decrease in gender inequality, they clearly do not tend to disappear completely (Cooper and Smith 2011; Vasilchikova and Kukharuk 2009; Thomas and Gunnell 2010; Health, United States 2010).

The second statement which appeared relatively recently is also not fully accepted but does not cause such violent disputes. This is a different level of bisexuality among women and men. If gay men and even overt bisexuals are very noticeable among men but make up a relatively small percentage, the distribution among women is different. According to the most common modern ideas and sociological polls (not contradicting everyday experience), a considerable part of heterosexual women is characterized by a slight degree of bisexuality (Dickson et al. 2013; Wienke and Whaley 2015; Field et al. 2013). With today's great freedom of sexual morals, it easily turns from friendly hugs and kisses into having some lesbian experience among a significant proportion of women.

The controversy over both allegations is not finished and is unlikely to be completed in the near future, however, the author will rely on his predictions on those ideas that seem most appropriate to him even if in fact they carry a certain amount of sexist prejudice.

In the most idealized form that will never be achieved anywhere (see the reasons below), the configuration of the social and gender structure of the future Western society, in the author's opinion, will consist of three groups (strata). Below, to heighten the effect, these strata are described almost as ascriptive estates of the feudal society, but in fact, even in times of the most pronounced manifestation of such a configuration of society, all three strata will not have sharp boundaries and often friends and close relatives, belonging to different strata, will maintain close communication with each other. The topmost stratum (tentatively 10 %) will consist of politicians, top managers, financiers, programmers, engineers, and scientists. This will be a predominantly (conditionally two-thirds) male community, in which the gender roles inherent in modern times, and even traditional times, will partially remain.

The second stratum, the most numerous (conditionally half of the working population), includes people who have, although not permanent but normally paid jobs, ensuring a comfortable life at their own expense and at the expense of non-overdue loans. Two groups will prevail in this stratum: 1) people employed in more or less computerized systems (and threatened with job cut due to further automation of processes); and 2) those who will be engaged in the enhanced above-mentioned ‘care work’ discussed above. The first group as a whole is unlikely to have any gender peculiarities; rather, its peculiarity will be a constant rejuvenation, the reduction, in the first place, of older workers who are the least prepared for rapid changes in technology and their work responsibilities. The second, and apparently, larger group will be sharply dominated by women, primarily women-extroverts. Let us conditionally assume that in the sum of both groups the proportion of women will be from 60 % to two thirds. Naturally, most of them will not be able to find husbands (or partners for long-term relationships) with comparable incomes and social status. Men from the upper stratum will be occupied either by women of their own stratum, or by young beauties, and men from the lower stratum, which will be discussed below, are unlikely to be highly valued. Therefore, a significant proportion of women will form lesbian and quasi-lesbian unions, not excluding temporary and even long-term relationships with socially ‘unworthy’ men or short-term and unpromising relationships with men from the upper stratum.

The lowest third stratum (taking into account previous estimates, it should account for about 40 % of the working-age population) will consist mainly of men, introverts and especially introvert men. Let us note that an exemplary man from the mass estates of the 19th and 20th centuries, a silent introvert with skillful hands, physically strong, tough and hardworking, loyal to his family and profession will be just as much and even a more unnecessary type than a talkative idler and spendthrift in the countries of the first world. This type of people will not starve or live in poverty, receiving various individual or general benefits, but will have a low social status and an income which is noticeably lower than the median. They will end up with dishonorable activities, such as repair work, particularly dirty and unpleasant jobs (e.g., working in morgues or waste sorting for further processing) that have not yet been automated and transferred to robots; with maintenance at the expense of sexual partners; with frankly criminal activities (theft, street fraud, drug trafficking, etc.). Obviously, this stratum will include a disproportionately large number of descendants of recent immigrants with a different color of skin, often with a different religion (primarily Muslim), lower levels of education, as well as representatives of traditional social lower strata and a crumbling working class.

A natural question arises: why unlike other technological revolutions exactly robotization will deprive such a large segment of society of work. After all, as a rule, the previous technological changes destroyed the old professions, but also gave rise to an even greater number of new ones. I would be glad to believe the optimists who suppose that something similar is waiting for us in the near future. Nevertheless, it is impossible not to see that at the beginning of robotization the proportion not of changes in occupations, but a direct transfer of human occupations to mechanisms – automatic and robotic – is unusually large. Besides, not all the economic changes of previous centuries led to a rapid job creation; for example, in England the problem of ‘unnecessary’ people, displaced from the labor process, generated by enclosing, lasted for many centuries, and was finally resolved only after the Industrial Revolution.

Thus, a significant segment of population is formed with a predominance of men from poor families who have neither intelligible occupations nor prospects for the future. Nowadays, it is widely believed that the main occupation of these people will be computer games and social networking. This is partly true, especially for the youngest members of this stratum who love to play, discuss their games with friends and have frivolous conversations with girls, as well as, on the contrary, for the oldest part of the people who love to read newspapers (political and economic sites) and discuss what they have read with friends and acquaintances. However, for most people of the most active ages computer games, even using the most advanced means of creating virtual reality and fruitless conversations in the network, are insufficient; they need real physical and / or communication activity that has been provided by productive (or counterproductive, e.g. military) activity throughout the entire previous history of mankind. At least four aspects that cause frustration in people who have only occasional work or, who do not have any paid occupation at all, can be specified:

– isolation from human society (virtual communication with partners in social networks and computer games is not enough for healthy people of young and middle age);

– a sense of worthlessness, being excluded from life;

– low income, noticeably smaller than median, and, accordingly, smaller opportunities in comparison with other people, even not wealthy ones;

– disrespect on the part of more successful people, especially those of the opposite sex (which, of course, applies more to men).

It can, of course, be assumed that the Western society will be going so far that social success will no longer play an important role in relations between people and girls will be indifferent to whether her partner has housing and a car, whether he can afford to give her generous presents, pay (or at least share) travel expenses, financially support her during pregnancy and when caring after the babies, bear the cost of maintaining their common children, etc. But it is still hard for me to believe that traditional attitudes, having not only social but also biological roots, will change at such a pace, even despite the examples of Iceland or Sweden, indicating the quickness of changes in gender roles.

This creates a very dangerous situation fraught with social cataclysms. Crime which has decreased over the past decade and a half in almost all developed countries primarily due to the transfer of aggression from the real world to the virtual world will again manifest itself in the real world which will further intensify the destruction of the social world characteristic of the social states of the West.

Another consequence of accelerated automation and robotization in production and social processes is related to the sphere of economy. The ‘hedonistic’ amendments that appeared in the 1990s in statistical reports, when calculating inflation, were at first perceived only as attempts to underestimate inflation (which in part they were). It would seem that it is not so important to anyone that a computer purchased this year for the same thousand dollars as in the past performs mathematical operations three times faster and has twice the memory, if the actual consumer properties of the computer have increased just by a few percent or remained about the same. However, gradually similar improvements in consumer properties (at least as a formal parameter) began to seize an ever wider range of goods, and they were of increasing interest to consumers, especially young ones. If we add to this the real increase in the output of computers, smartphones, and other such things per worker and a decrease in his salary (especially when transferring production to a third world country), then the fictitious understatement of inflation eventually resulted in a sharp slowdown in actual inflation and even real deflation, leading to reduction of final consumption (why buy today if tomorrow it will be cheaper). As noted by L. Grinin and A. Korotayev (2014), the current deflation has some similarities with the deflation, characteristic of B-phases of the Kondratieff cycles of the gold standard times. Until very recently, consumer deflation (or almost zero inflation) of prices was offset by rising stock prices (total world capitalization) and commodity prices. However, at present the growth of capitalization has slowed down and has become very unstable.

In reality, in the long run it would be beneficial (although very painful) for the states burdened with high public debt to raise inflation to 5–10 % or more and pay off their debts. However, the introduction of a high discount rate with deflationary trends in the economy would threaten with an even greater series of troubles: high costs of servicing the public debt, significant, or even almost complete, attenuation of investment activity and in the worst case disintegration of the banking system, to a significant degree severed from the real situation in the economy (e.g., by expanding the scope of the parallel cryptocurrency system). A way out of this slippery situation has not yet been found and radical proposals for de-dollarization of the world economy threaten to have destructive consequences for so many economic and political actors that they cannot be implemented in the foreseeable future. One can only hope that the emergence of new goods and services will give impetus to the global economy and lead it out of its current state of stupor. Or, in addition to economic and social changes, we are also in the process of gigantic transformations in the financial sector, fundamentally changing the role of money; for example, the main function of money is being transformed from a means of payment into a means of assessing the prospectiveness of a borrower which is usually a negative value (Frumkin 2014: 103–142). Social ratings in China can be considered, in one way or another, a manifestation of this tendency, which scares us with the vague but terrible tendency of the transition from the debt economy to political unfreedom.

Nevertheless, the traditional, long-lasting and unpleasant way out of the economy of debts cannot be excluded (Reinhart and Rogoff 2011). The fact that this did not happen in Japan, which for a long time combined deflation with a high public debt and is not happening now in other countries with growing debts, still does not eliminate this possibility in the future. As a very remote analogy, one can cite the attitude towards immigrants in Western countries. Until quite recently, right-wing politicians and outside observers were surprised at how the majority in the Western society continues to welcome people with different customs, a different level of culture, a different physical appearance, etc., despite the rising costs of providing social assistance and increasing number of excesses (including terrorist attacks). But in recent years, as mentioned above, for one reason or another, a significant part of voters has changed their attitude towards migrants which has become one of the main factors of political change in Western countries.

However, let us leave the current turmoil and cataclysms of the near future and return to the supposed world that was described several pages earlier. If the social order described above had existed long enough, the changes would have affected not only the social-gender structure of the society but also the social-gender structure of humanity itself or at least the population of Western countries. The futility of non-top-quality male introverts in the social division of labor, their danger to social order, low demand for them in the marriage market and simply low social status would lead to a reduction in their number in the population. Of course, not due to the shooting of unnecessary individuals (even East Asia is already far from such actions), but due to the regulation of sex during childbirth (which, as can be expected, will be reached soon enough). Women's unions, single women and even heterosexual families with low husband's status would prefer to have daughters rather than sons who would dramatically change the sex ratio.

The Сollapse of the New Social Structure and the Prospects for a Complete Restructuring of Human Society (the Second Half of the 21st Century)

However, as can be supposed, the above-described society of individual personal services will hardly survive for long (more than 1–1.5 generations), since it will erode from two sides.

1. The first side is the drop in demand for individual services that require human contact due to the possibility, cheapness and even the desirability of replacing them with the services of robots that have some form of artificial intelligence. If yesterday we considered the game of chess with a computer something second-rate, today machines beat the world champions and most of the chess games in the world are held between humans and the electronic device (e.g., a game of Go already took place between man and machine). Apparently, in about 10–15 years, a robotic motor transport without a driver will no longer seem exotic and dangerous on the roads which will dramatically reduce the number of taxi drivers, couriers, peddlers, etc.

In future, the services of robots will be widely used in activities now associated with contact between people. Electronic waiters, nurses, companions, sexual partners for many people will become not only morally permissible (tolerated because of cheapness) but even more desirable than people (and animals) that they replace. For example, for the author of the paper, a great cat lover, it is hard to imagine how electronic toys can be kept at home instead of live, warm and unpredictable creatures but now electronic pets are widespread in Japan and are becoming common in other countries of East Asia and even in the USA. It is quite possible that in 30–40 years or even earlier, keeping real pets will be considered as breeding insanitary conditions, torture of animals and generally an anachronism, whereas their electronic similarities with artificial animal intelligence will be the norm. The widespread occurrence of sex toys and robotic imitations of sexual partners seems to indicate that in other areas of human relations the population of East Asia will not be so interested in occupations involving personal contacts and the described structural changes will affect the East Asian countries to a lesser extent than Western countries.

In addition, the usual glasses, walking sticks, hearing aids, cardioprostheses, artificial pupils, etc. will be complemented by exoskeletons, limb prostheses, controlled by the human nervous system, new sense organs, etc., and turning people into cyborgs will become a natural process without encountering obstacles and without causing active protest. Thus, the growing community of cyborgs (people) and robots will further break the prejudices against the use of robots in the expanded area of care work.

It is also impossible to exclude the option (more popular in futuristic essays than the one described above) that people will soon become accustomed to the fact that robots will perform jobs done exclusively by humans. In this case, the world described by me will only begin to be created and will not take shape until it is destroyed under the influence of new changes. However, it seems to the author that intimate (in every sense of the word) contact between people will not fall victim of modern computer technologies as soon as typewriters or vinyl records. As a remote analogy, one can point out non-living, but important for the consciousness of educated people paper books that continue to be published despite the rapid development of e-books and other gadgets that can replace books and at the same time provide the reader with additional features and amenities.

2. The second side that will not allow the world described above to fully form is medical and especially eugenic intervention in human genetics. Currently, in developed countries, 99–99.5 % of children survive to adulthood, i.e. natural selection among the live-born has virtually ceased. Given that at present a live birth is an infant at a gestation of 22 weeks with a weight of 500 grams than even children with a greater risk of genetic abnormalities survive.

There are different opinions on the extent to which the cessation of natural selection among live births affects the accumulation of mutations (Reed and Aquadro 2006). According to A. Kondrashov (2017), the degree of degradation ranges from 1–2 to 10 % per generation and Kondrashov himself is inclined to the upper estimate. A number of other biologists considers these estimates to be overestimated, disputes on the Internet (e.g., in A. Markov's[2] blog) have revealed great disagreements and almost the same range of opinions was observed both among biologists and amateurs.

The main arguments against degeneration (or rapid degeneration) due to the cessation of natural selection were as follows:

а) The ‘reserves of live-born’ mainly insures against extinction in difficult conditions and allows people to quickly occupy ecological niches, but plays a small role in eliminating harmful mutations.

b) Modern medicine allows eliminating of the influence of moderate genetic abnormalities on the physical and mental health of people.

c) The loss of many qualities important for existence in the wild does not affect the quality of life and human capabilities in the modern world (e.g., a slight decrease in the sense of smell, or vision).

d) Sexual selection, sexual attractiveness of the more adequate people, their achievements largely replace natural selection.

In response, the following counterarguments were given (supplemented by the author's considerations):

a) It is unlikely that death in childhood and adolescence of 60–75 % of the born, naturally including the most sick and weak, is not directly related to natural selection. In particular, the prematurity and the helplessness of human children, compared with the young of other primates, indicates that the prenatal selection of the late stages of pregnancy is reduced in the Homo sapiens species.

b) Even if the influence of moderate genetic abnormalities has little effect on health of the first generations without selection, then with further accumulation of harmful mutations in future generations, the previously accumulated and additional harmful ‘genetic cargo’ will be added.

d) Sexual selection would prevent the accumulation of harmful mutations if people with genetic abnormalities completely left the marriage market and did not find people like themselves and produce offspring of about the same number as completely healthy people. Sexual selection with the social support of the sick and the weak contributes not to ‘washing out’ harmful mutations but to the stratification of humanity into different varieties without any genetic interference in human nature.

Some biologists will certainly find arguments against these social Darwinist theses and other biologists will find a new batch of counter-arguments but the author, far from biological problems, ends the discussion at this point.

No matter who is right in the previous dispute, it is quite obvious that in the next half of the century the degeneration of humanity will not take on a catastrophic size, even if modern medicines and electromagnetic pollution of the ether actually accelerate mutations. For the topic under discussion, the acuteness of the attitude of people to the problem is more important than the acuteness of the problem itself.