Which Countries Generate Kondratieff Waves in Global GDP Growth Rate Dynamics in the Contemporary World?

Almanac: Kondratieff waves: Kondratieff's Theoretical Legacy: Perspectives from Modern Times

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/978-5-7057-6273-6_10

Abstract

It is shown that the Kondratieff wave dynamics in the growth rates of global GDP is generated now by the developing countries, while in the previous era the Kondratieff dynamics was generated primarily by the most economically developed countries of the First World. We re-visit the question of the presence of the Kondratieff waves in the world GDP dynamics. We find that, though in the post 1960 series they are quite visible at the global level, they are hardly visible in the GDP growth rates of the economically developed countries where the Kondratieff wave component (still detectable with special techniques) is almost entirely overwhelmed by the secular trend towards the decline of the GDP growth rates. After analyzing how much this trend is connected with the decline of the population growth rates and the decline of the share of investments in GDP, we move to the analysis of the Kondratieff waves in the GDP growth rates of the developing countries where they turn out to be much more pronounced and visible, which allows us to conclude that the K-waves are currently generated by the Third World. We also show that in the developing countries a pronounced Kondratieff wave dynamics is accompanied by an overall upward trend (that stands in sharp contrast with the pronounced downward trend observed in the developed economies). Finally, we analyze Kondratieff waves in the efficiency of investments as well as demographic characteristics of the developing countries, which allows us to forecast that the GDP growth rates in the developing countries are likely to also step on the downward secular trend starting with the sixth Kondratieff wave.

Keywords: Kondratieff waves, developing countries, developed countries, economic growth, global dynamics, GDP.

1. Introduction

A Russian economist of the 1920s, Nikolai Kondratieff observed that the historical record of some economic indicators then available to him appeared to indicate a cyclic regularity of phases of gradual increases in values of respective indicators followed by the phases of decline (Kondratieff 1922: Ch. 5; 1925, 1926, 1928a, 1928b, 1935, 1979, 1984, 1998, 2002, 2004). The period of these apparent oscillations seemed to him to be around 50 years.[1] This pattern was found by him with respect to such indicators as prices, interest rates, foreign trade, coal and pig iron production for some major Western economies (first of all Britain, France, and the United States), whereas the long waves in pig iron and coal production were claimed to be detected since the 1870s for the world level as well.

Kondratieff himself identified the following long waves and their phases (see Table 1).

Table 1. Long waves and their phases identified by Kondratieff

|

Long Wave Number |

Long Wave Phase |

Dates of the Beginning |

Dates of the End |

|

The First |

A: upswing |

The end of the 1780s or beginning of the 1790s |

1810–1817 |

|

B: downswing |

1810–1817 |

1844–1851 |

|

|

The Second |

A: upswing |

1844–1851 |

1870–1875 |

|

B: downswing |

1870–1875 |

1890–1896 |

|

|

The Third |

A: upswing |

1890–1896 |

1914–1920 |

|

B: downswing |

1914–1920 |

|

The subsequent students of Kondratieff cycles additionally identified the following long waves in the post-World War I period (see Table 2).

Table 2. ‘Post-Kondratieff’ long waves and their phases

|

Long wave |

Long wave phase |

Dates of the beginning |

Dates of the end |

|

The Third |

A: upswing |

1890–1896 |

1914–1920 |

|

B: downswing |

1914–1928/29 |

1939–1950 |

|

|

The Fourth |

A: upswing |

1939–1950 |

1968–1977 |

|

B: downswing |

1968–1974 |

1984–1991 |

|

|

The Fifth |

A: upswing |

1984–1991 |

2007–2008 |

|

B: downswing |

2007–2008 |

? |

Sources: Mandel 1980; Dickson 1983; van Duijn 1983: 155; Wallerstein 1984; Goldstein 1988: 67; Modelski and Thompson 1996; Pantin and Lapkin 2006: 283–285, 315; Ayres 2006; Linstone 2006: Fig. 1; Tausch 2006: 101–104; Thompson 2007: Table 5; Jourdon 2008: 1040–1043; Korotayev and Grinin 2012a, 2012b; Korotayev and Tsirel 2010a, 2010b, 2010c; Korotayev, Zinkina et al. 2011a; Lynch 2004; Akaev, Sadovnichy, and Korotayev 2010; Akaev, Fomin et al. 2011; Akaev, Grinberg et al. 2012; Akaev, Korotayev et al. 2017; Grinin, Korotayev, and Tsirel 2011, Grinin, Korotayev, and Tausch 2016.

Nowadays, Kondratieff's wave theory has a rather peculiar status in the academic world. On the one hand, it has numerous supporters (see, e.g., Phillips 2016, 2018; Phillips and Linstone 2016; Berry and Elliott 2016; Nefiodow 2016; Norkus 2016; Thompson 2016; Tausch 2016; Gallegati 2016; Gallegati et al. 2017; Grinin, Korotayev, and Tausch 2016; Grinin L., Grinin A., and Korotayev 2017; Devezas et al. 2017; Modis 2017; Sokolov et al. 2017; Akaev, Korotayev et al. 2017; Coccia 2018). On the other hand, it is rejected by the majority of mainstream economists (see, e.g., Garvy 1943; Rothbard 1984; Zarnowitz 1985; Mankiw 1989; 2008: 740; 2015: 420; Block and Rockwell 2007: 166–169; Focacci 2017) and even by some world-system scholars (e.g., Morineau 1984; Plys 2012, 2014).

This is connected with the fact that many economists have failed to detect Kondratieff waves in many important economic indicators, including GDP growth rates, for the majority of modern developed economies (see, e.g., Van Ewijk 1982; Metz 1998, 2006; Diebolt and Doliger 2006, 2008; Diebolt 2012, 2014).

In this article we will argue that this might be connected with the point that in the present epoch, Kondratieff waves in the global GDP dynamics are generated by the developing (rather than developed) economies. We will re-visit the question of the presence of the Kondratieff waves in the world GDP dynamics. We will see that although in the post 1960 series they are quite visible at the global level, they are hardly visible in the GDP growth rates of the economically developed countries where the Kondratieff wave component is almost entirely overwhelmed by the secular trend towards the decline of the GDP growth rates. After analyzing how much this trend is connected with the decline of the population growth rates and the decline of the share of investments in GDP, we will move to the analysis of the Kondratieff waves in the GDP growth rates of the developing countries where they appear to be much more pronounced and visible, which will allow us to conclude that in the present epoch the K-waves are generated by the Third World. We will also show that in the developing countries pronounced Kondratieff wave dynamics is accompanied by an overall upward trend (that stands in a sharp contrast with the pronounced downward trend found in the developed economies). Finally, we analyze Kondratieff waves in the efficiency of investments as well as demographic characteristics of the developing countries, which will allow us to forecast that the GDP growth rates in the developing countries are also likely step on the downward secular trend starting with the sixth Kondratieff wave.

2. Kondratieff Waves in the Global GDP Dynamics

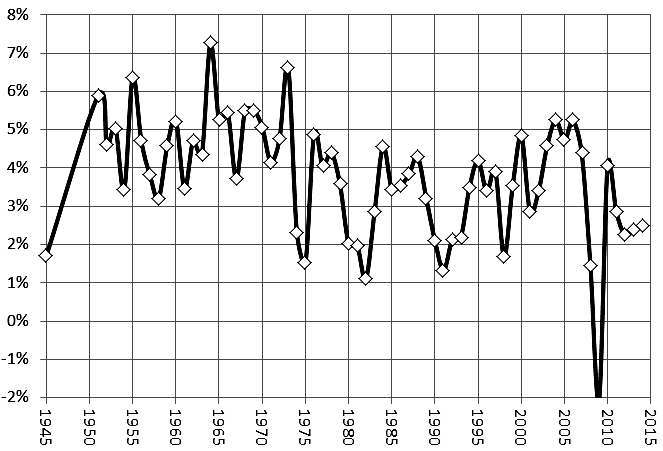

To begin with, let us consider the dynamics of

GDP growth at the level of the World System as a whole. The general dynamics of

annual growth rates

of world GDP for 1945–2014 looks as follows (see Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1a. Dynamics of annual growth rates of world GDP (% per year), 1945–2014

Sources: Maddison 2010; World Bank 2019.

Within this dynamics, unusually clearly visible[2] K-waves attract attention first of all. However, the Kondratieff wave component becomes especially visible if a LOWESS (= LOcally WEighted Scatterplot Smoothing) line is fitted (see Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1b. Dynamics of annual growth rates of world GDP (% per year), 1945–2014. Maddison/World Bank empirical estimates with fitted LOWESS (=LOcally WEighted Scatterplot Smoothing) line. Kernel: Triweight. % of points to fit: 50

Note that we are dealing precisely with the Fourth and Fifth Kondratieff waves identified by the students of K-cycles (see Table 2 above). Special attention should be paid to the fact that the peak of the current Kondratieff wave was noticeably lower than the previous peak, whereas previously the peak of every next wave always turned out to be higher than the peak of the previous cycle (see, e.g., Korotayev and Tsirel 2010a, 2010b, 2010c; Korotayev and Grinin 2012a, 2012b; Korotayev, Khaltourina et al. 2010; Grinin, Korotayev, and Tausch 2016). This serves as an additional confirmation of the fact that in the 1970s, most of the global macrotrends that had been observed during the preceding centuries and millennia were reversed (see, e.g., Korotayev and Bozhevolnov 2010; Korotayev 2015a; Korotayev, Goldstone, and Zinkina 2015; Korotayev 2020). However, an appreciable part of the academic community continues to ignore this fact, maintaining faith in the continuous ‘acceleration of the pace of historical development’ and refusing to see that since the early 1970s the pace of historical development is no longer accelerating, but rather slowing down (cf. Modis 2002, 2020).

3. Are There

Kondratieff Waves in the GDP Growth Rates

of the Most Economically Developed Countries?

This slowdown is particularly evident for the group of the most economically developed countries (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Dynamics of annual GDP growth rates (% per year) in economically developed countries, 1961–2014

Source: World Bank 2019: NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG. The notions of the ‘economically developed countries’ ≈ ‘the first world countries’ ≈ ‘the World System core countries’ are operationalized in this paper as High income OECD countries according to the World Bank classification.

As can be clearly seen in Fig. 2, over the last decades, the linear downward trend in the rate of GDP growth has been dominant in economically developed countries (accounting for 40 % of all the variation of the GDP growth rates). Moreover, even the upswing phase of the fifth Kondratieff wave only slowed down this trend, but did not stop it completely.

Thus, unlike for the world GDP growth rates, the K-waves in the developed economies' GDP growth rates are not directly visible in Fig. 2. However, they can still be seen quite clearly if we apply the very technique widely used by Kondratieff in order to detect long waves in the dynamics of economic indicators, that is, to plot not the indicator dynamics directly, but rather the dynamics of deviations fr om the secular trend smoothed by means of a nine-year moving average (e.g., Kondratieff 1979: 626) (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Dynamics of annual GDP growth rates in economically developed countries, 1961–2014: deviations from the secular downward linear trend (identified in Fig. 2) smoothed by means of a nine-year moving average, per cent points

After the application of this procedure, in Fig. 3 one can clearly see the end of the upswing of the fourth Kondratieff wave, its downswing, as well as the upswing and downswing of the present, fifth, K-wave (consisting in its turn of two Kuznets swings [see Korotayev and Tsirel 2010a, 2010b, 2010c]).

Of course, the first explanation that comes to mind in this case is to explain the slowdown in GDP growth rates in developed countries by the reduction in population growth rates, as it was quite real in the years under consideration (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Dynamics of relative annual growth rates of the population in economically developed countries, %, the early 1950s – the early 2010s

Source: UN Population Division 2017.

However, an analysis of the data on the dynamics of GDP growth per capita in economically developed countries shows that the deceleration of GDP per capita growth rates (see Fig. 5) played the main role in reducing GDP growth in the economically developed countries.

Fig. 5. Dynamics of annual growth rates of GDP per capita (% per year) in economically developed countries, scatterplot with a fitted trend line, 1961–2014

Source: World Bank 2019: NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG.

After 1973 in economically developed countries there was observed a pronounced tendency toward deceleration of not only GDP but also of the GDP per capita growth rates, which shows that it is impossible to explain the slowdown in the GDP growth rates of developed countries first of all by the deceleration in their population growth rates. At the same time, it should be noted that the Kondratieff wave component is still visible here, but in an extremely blurred form (especially when compared with the dynamics of this indicator for developing countries, see below). Actually, this dynamics during the downswing phase of the fourth Kondratieff wave was manifested in the fall of per capita GDP growth rates in developed countries significantly below the downward trend line with the return within the fifth K-wave back to the downward trend line during the fifth K-wave upswing. However, to make the K-waves in the GDP per capita growth rate dynamics clearly visible, one should apply again the technique widely used by Kondratieff in order to detect long waves in the dynamics of economic indicators, that is, to plot not the indicator dynamics directly, but rather the dynamics of deviations from the secular trend smoothed by means of a nine-year moving average (e.g., Kondratieff 1979: 626) (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Dynamics of annual GDP per capita growth rates in economically developed countries, 1961–2014: deviations from the secular downward linear trend (identified in Fig. 5) smoothed by means of a nine-year moving average, per cent points

Again, after the application of the above specified procedure, in Fig. 6 one can clearly see the end of the upswing of the fourth Kondratieff waves, its downswing, as well as the upswing and downswing of the present, the fifth K-wave (consisting again in its turn of two Kuznets swings [see Korotayev and Tsirel 2010a, 2010b, 2010c]).

In this regard, the dynamics of the share of investments in the GDP in the first world countries turn out to be of considerable interest (see Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Dynamics of the share of investment (%) in GDP of economically most developed countries, 1960–2013

Source: World Bank 2019: NE.GDI.FTOT.ZS.

This diagram clearly demonstrates that the steady decline in the economic growth rates of the first world countries in recent decades is not coincidental, while allowing to identify one of the most important factors of this decline – a no less systematic decline in the share of investments in the GDP of economically most developed countries. During the period under consideration, some systematic growth was observed only at its start, up to the year of the inflection of global trends, 1973.[3] Starting from 1973 and up to the present time, a systematic decrease of this indicator was observed in the first world countries. In its dynamics, however, there was a pronounced cyclical component corresponding to Juglar cycles.[4] In general, in the phase of the rise of these cycles in the Western economies there was an increase in the share of GDP spent on investment, whereas at the recession and depression phases this indicator decreased. However, since 1973, at the peak of each new Juglar cycle, the value of this indicator turned out to be much lower than at the peak of the previous cycle, and during the recession this indicator fell every time below the level of the previous recession, which created a systematic downward trend for the share of investments in GDP in the high-income OECD countries, confidently observed after 1973.

4.

Kondratieff Waves in the GDP Growth Rates

of the Developing Countries

At the same time, the developing countries demonstrate a very different dynamics. Let us begin its analysis by examining the dynamics of GDP in the developing countries (see Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Dynamics of annual GDP growth rates (% per year) in developing countries, 1961–2014

Source: World Bank 2017: NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG. The notion of ‘developing countries’ ≈ ‘the Third World countries’ ≈ ‘countries of the World System periphery (and semi-periphery)’ are operationalized in this paper as Low & middle income countries according to the World Bank classification.

As we can see, the dynamics of the annual growth rates of developing countries, actually demonstrates the most significant differences in comparison to those of highly developed countries. Here we are dealing with the wave component predominating in the expressed absence of any downward trend (and a pronounced upward trend as well). Thus, the Kondratieff wave dynamics in the growth rates of global GDP in the last decades of the Great Convergence is generated precisely by the developing countries, while in the previous era of the Great Divergence it was generated primarily by the most economically developed countries of the First World (see, e.g., Korotayev and Tsirel 2010а, 2010b, 2010c; Grinin, Korotayev, and Tsirel 2011; Grinin and Korotayev 2012, 2014b).

It appears appropriate to recollect at this point that in the 19th century, northwestern Europe witnessed the birth of capital-intensive and fossil-fuel based manufacturing. Spreading throughout Europe and the United States, these changes triggered an explosive growth of the gap in per capita incomes between the First and Third World that became known as the Great Divergence (see, e.g., Pomeranz 2000; Goldstone 2008, 2012; Clark 2008; Allen 2011; Sadovnichiy et al. 2014; Malkov et al. 2010a; Korotayev, Malkov et al. 2010; Korotayev 2014, 2015а; Grinin and Korotayev 2014a, 2015; Korotayev, Goldstone, and Zinkina 2015). In the 20th century, the Great Divergence peaked before the First World War and continued until the early 1970s, then, after two decades of indeterminate fluctuations, in the late 1980s it was alternated by the Great Convergence since the majority of the Third World countries reached economic growth rates that far exceeded those of most First World countries (e.g., Sala-i-Martin 2006; Korotayev and Khaltourina 2009; Spence 2011; Derviş 2012; Grinin and Korotayev 2014a, 2015; Akaev 2015; Malkov et al. 2010a, 2010b; Korotayev 2013, 2014, 2015a, 2015b; Malkov and Korotayev 2014; Korotayev, Andreev et al. 2014; Korotayev, Zinkina et al. 2011a, 2011b, 2012; Korotayev and de Munck 2013, 2014; Korotayev and Zinkina 2014b; Zinkina et al. 2014).

It is also noteworthy that, unlike the highly developed countries, during the peak of the fifth Kondratieff wave, the developing countries advanced in terms of their GDP growth rates to the peak level of the fourth K-cycle.

It seems appropriate to compare GDP growth rates in the developed and developing countries (see Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Dynamics of annual GDP growth rates (% per year) in developed and developing countries, 1961–2014

Source: World Bank 2019.

As one can see, at the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s, the GDP growth rates in developing countries were already somewhat ahead of those in the developed countries. However, given the fact that in those years in the developing countries the population growth rate reached its maximum (see Fig. 10) and was significantly higher than in the developed countries, the gap between the developed and developing countries in GDP per capita continued to grow,[5] and therefore the Great Divergence continued. In the 1990s, the GDP growth rates in the developing countries again rose markedly above those in the developed countries, but most of the developing countries had achieved by then a very marked decline in the birth rate, so everything was happening against the background of a fast decline in population growth rates in the developing countries.

Fig. 10. Dynamics of relative annual growth rates of the population of developing countries, %, early 1950s – early 2010s

Source: UN Population Division 2019.

Thus, in the 1990s, the developing countries began to overtake the developed ones not only in terms of GDP growth rates, but also as regards the GDP per capita growth rates, the gap between them began to narrow more and more, and the Great Convergence replaced the Great Divergence era. The processes of the Great Convergence have intensified significantly since 2000, when the GDP growth rates of the developing countries already outpaced significantly those in the developed countries against the background of the continuing decline in the population growth rates of developing countries, as a result of which, as we will see below, at the peak of the fifth Kondratieff wave these countries in terms of GDP per capita growth even managed to significantly outperform the peak of the fourth K-wave (see Fig. 11).

Fig. 11. Dynamics of annual per capita GDP growth rates (% per year) in developing countries, 1961–2014

Source: World Bank 2019.

As one can see, at the peak of the fifth Kondratieff wave the developing countries in sharp contrast to the developed countries were really able not only to achieve very high values that were obtained at the peak of the preceding wave, but even to noticeably outperform the previous peak.

In the light of the above said, it seems appropriate to consider the dynamics of the investment share in the GDP of the developing countries in comparison with this indicator for the developed countries (see Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Dynamics of the share of investments (%) in the GDP of developed and developing countries, 1960–2014

Source: World Bank 2019.

As one can see, in the 1960s, there was still a very significant gap between the developed and developing countries in the share of investment in GDP (in favor of the developing countries), which undoubtedly contributed to the continuation of the Great Convergence. By the mid-1970s, these shares were equal, and in the 1990s, the share of the developing countries began to noticeably exceed the share of the developed ones, and in the 2000s the gap between the developing and developed countries (in favor of the former) reached enormous proportions, which also significantly contributed to the development of the processes of the Great Convergence.

5. Kondratieff Waves in the Global Investment Efficiency

Let us also consider the dynamics of such an important macroeconomic indicator as the efficiency of investments (calculated as how many dollars of GDP growth are produced by one dollar of investment). One should note that in the global dynamics of this indicator, the Kondratieff cyclic component is again very clearly traced. In a predictable manner, in the upward phases of K-waves, the global efficiency of investments increases while in the downward phases it decreases (see Fig. 13).

Fig. 13. Dynamics of global investment efficiency, 1961–2013

Source: authors′ calculations based on the World Bank data (2017).

At the same time, a closer examination reveals that the developing and not the developed countries are the real generator of Kondratieff cyclical component in the modern world. Indeed, in the dynamics of the developed countries, a downward trend predominates: if in the early 1960s every dollar of investment gave 25 cents of GDP growth, by now this indicator has fallen almost fivefold. At the same time, Kondratieff cyclical component in the dynamics of economically developed countries is barely visible (see Fig. 14).

Fig. 14. Dynamics of investment efficiency in the economy of developed countries, 1961–2013

Source: authors' calculations based on the World Bank data (2017).

Again, the dynamics of the considered indicator in relation to the developing countries is radically different from what we observed in relation to the developed countries (see Fig. 15).

Fig. 15. Dynamics of investment efficiency in the economies of the developing countries, 1965–2014

Source: authors' calculations based on the World Bank data (2017).

As we see, Kondratieff wave component is expressed incomparably clearer when applied to economically developed countries. In the era of the Great Convergence, these are the developing and not the developed countries that act as the main drivers of the Kondratieff wave dynamics. At the same time, the following point attracts attention: at the peak of the fifth (current) Kondratieff wave, the developing countries have failed to reach the level of investment efficiency that they had at the peak of the previous (fourth) Kondratieff wave. This suggests that the majority of the middle income countries are likely to experience in the forthcoming decades a slowdown in economic growth rates that could be similar to the one that has been observed for the economically developed countries for several decades since the early 1970s. In this regard, the trajectory of the decline in GDP growth rates of economically developed countries observed in recent years and presented above in Fig. 2 may well be considered as ‘memories of the future’ for the middle income countries.

6. Why Can We

Expect the Developing Countries

to Step on the Downward Secular Trend Starting

with the Sixth Kondratieff wave?

Particular attention should be paid to the following point: at the peak of the current (fifth) Kondratieff wave, despite a noticeable reduction in the macroeconomic efficiency of investments the developing countries managed , to reach the growth rates of per capita GDP exceeding those at the peak of the previous (fourth) Kondratieff wave, mostly due to the two following points:

1) It was the peak of the fifth Kondratieff wave when the developing countries received the maximum of their demographic bonus.[6] As we could see above, at the upswing phase of the fifth Kondratieff wave, the rapid acceleration of GDP growth rates in developing countries (see Fig. 8 above) was accompanied by a very rapid (by one third in just two decades) decline in population growth rates, resulting in a particularly strong increase in per capita GDP growth during this period. However, this issue can be looked at from different perspectives. Why was the reduction in the population growth rates in the developing countries at the upswing phase of the fifth Kondratieff wave quite naturally accompanied by such an impressive acceleration in GDP growth rates per capita? The fact is that the abovementioned decline in population growth rates was due to a very rapid reduction in the birth rate, since most developing countries at that time were in the midst of the second phase of their demographic transition. This led to a marked improvement (from an economic point of view) in the structure of the population of developing countries. Indeed, during the period in question, in developing countries, the number of underage children per a working age adult decreased very significantly, but in the same period, the population did not get aged to such an extent as to ‘compensate’ the decrease in the number of underage dependents per worker by the number of the old age dependents on him/her. As a result, during the entire upswing phase of the fifth Kondratieff wave in the developing countries there was a significant increase in the share of working age population in the general population and, consequently, a significant reduction in the number of dependents per worker, which operated as a significant factor that increased the rate of growth of GDP per capita in these countries.

However, as shown in Fig. 17, by now the majority of economically developing countries are already finishing to receive their demographic bonus. The fertility rate in many of them (China, Iran, Thailand, etc.) has already dropped significantly below the replacement level, and any further substantial fertility rate decreases are not likely there, so the potential for reducing the demographic burden by decreasing the share of dependents of younger ages in the total number the population in this case has been already exhausted. On the other hand, the population aging here begins to manifest itself more and more, the proportion of dependents of older age in the total population begins to grow at an ever-increasing rate, which ceases to be compensated by a decrease in the share of dependents of younger ages. This means that the total number of dependents per worker increases. The demographic bonus is replaced by a demographic onus (see, e.g., Ogawa, Kondo, and Matsukura 2005; Park and Shin 2015; Goldstone 2015). If in the upward phase of the fifth Kondratieff wave the demographic processes in developing countries (through the mechanisms of the demographic bonus) contributed to the acceleration of GDP per capita growth, then in the coming decades, in economically developing countries, the same processes (through the mechanisms of the demographic onus) would contribute to a slowdown in rates of per capita GDP growth.

Fig. 16. The dynamics of the percentage of the population of working age (15–65 years) in the total population of developing countries, 1950–2015, with a medium forecast of the United Nations until 2050

Source: UN Population Division 2019.

2) As Fig. 15 indicates, the developing countries (unlike the developed ones) succeeded in raising the efficiency of investments at the upswing phase of the fifth Kondratieff wave. However, at the peak of the fifth wave they failed to surpass the level of efficiency that they reached at the peak of the fourth wave. The fact that they were able to exceed the growth rates of GDP per capita of the fourth wave at the peak of the fifth wave is connected not only with the demographic bonus at the time, but also with the fact that a tremendous increase (almost twofold!) occurred between the peak of the fourth and the peak of the fifth K-waves in the share of investment in the GDP of these countries (see Fig. 10 above). The lack of growth in investment efficiency at the peak of the fifth K-wave relative to the fourth one was more than compensated by the growth in the volume of these investments. However, there is no reason to expect a similar increase in the share of investment in the GDP of developing countries at the peak of the sixth Kondratieff wave. Rather, one should expect a decline in this share; in particular, this refers to the share of investment in the GDP of the major modern locomotive of developing countries – China (see, e.g., Grinin et al. 2014).

Thus, there are grounds to assume that developing countries at the peak of the fifth Kondratieff wave achieved record-high growth rates of GDP per capita, which at the peak of the sixth K-wave they are unlikely to surpass.[7]

7. Conclusion

Hence, the Kondratieff wave dynamics in the growth rates of global GDP in the recent Great Convergence decades is generated precisely by the developing countries, while in the previous era of the Great Divergence the Kondratieff dynamics was generated primarily by the most economically developed countries of the First World. At the same time, in sharp contrast to the developed countries, the developing states at the peak of the fifth Kondratieff wave not only achieved very high growth rates of GDP per capita attested at the peak of the preceding wave, but even significantly exceeded them. It is also shown that the dynamics of the share of investments in GDP played an important role in the processes of transformation of the Great Divergence into the Great Convergence. Back in the 1960s, there was a very significant gap in the share of investment in GDP between the developed and developing countries in favor of the developed countries, which undoubtedly contributed to the continuation of the process of the Great Convergence. By the mid-1970s, these shares became equal. In the 1990s, the share of developing countries began to noticeably exceed the share of developed countries, so in the 2000s the gap between the developing and developed countries (in favor of developing ones) had reached enormous proportions, which appears to be tightly connected with the process of transferring the role of a generator of K-waves in the global GDP growth rate dynamics from the developed to developing countries.

References

Acemoglu D. 2009. Introduction to Modern Economic Growth. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Akaev A. A. 2015. From the Era of the Great Divergence to the Era of the Great Convergence. Mathematical Modeling and Forecasting of Long-Term Technological and Economic Development of World Dynamics. Moscow: URSS. In Russian (Акаев А. А. От эпохи великой дивергенции к эпохе великой конвергенции. Математическое моделирование и прогнозирование долгосрочного технологического и экономического развития мировой динамики. М.: URSS).

Akaev A., Fomin A., and Korotayev A. 2011. The Second Wave of the Global Crisis? On mathematical analysis of some dynamic series. Structure & Dynamics 5(1): 19–29.

Akaev A., Fomin A., Tsirel S., and Korotayev A. 2011. Log-Periodic Oscillation Analysis Forecasts the Burst of the ‘Gold Bubble’. Structure & Dynamics 5(1): 3–18.

Akaev А. А., Grinberg R. S., Grinin L. E., Korotayev A. V., and Malkov S. Y. (Eds.) 2012. Kondratieff Waves: Aspects and Prospects. Volgograd: Uchitel. In Russian (Акаев А. А., Гринберг Р. С., Гринин Л. Е., Коротаев А. В., Малков С. Ю. (Ред.) Кондратьевские волны: аспекты и перспективы. Волгоград: Учитель).

Akaev A. А., Korotayev А. V., and Fomin А. А. 2011. On the Causes and Possible Consequences of the Second Wave of the Global Crisis. Globalistics – 2011. The Ways to Strategic Stability and the Problem of Global Governance / Ed. by I. I. Abylgaziev, and I. V. Ilyin, pp. 233–241. Moscow: МАKS-Press. In Russian (Акаев А. А., Коротаев А. В., Фомин А. А. О причинах и возможных последствиях второй волны глобального кризиса. ГЛОБАЛИСТИКА – 2011. Пути к стратегической стабильности и проблеме глобального управления / Ред. И. И. Абылгазиев, И. В. Ильин, с. 233–241. Москва: МАКС-Пресс).

Akaev A. А., Korotayev А. V., and Fomin А. А. 2012. On the Causes and Possible Consequences of the Second Wave of the Global Financial and Economic Crisis. Modeling and Forecasting of Global, Regional and National Development / Ed. by A. A. Akaev, А. V. Korotayev, G. G. Malinetskiy, and S. Y. Malkov, pp. 305–336. Мoscow: LIBROKOM/URSS. In Russian (Акаев А. А., Коротаев А. В., Фомин А. А. О причинах и возможных последствиях второй волны глобального финансово-экономического кризиса. Моделирование и прогнозирование глобального, регионального и национального развития / Ред. А. А. Акаев, А. В. Коротаев, Г. Г. Малинецкий, С. Ю. Малков, с. 305–336. М.: ЛКИ/URSS).

Akaev A. А., Korotayev А. V., and Malkov S. Y. (Eds.) 2014. The Current Situation and the Outlines of the Future. Complex System Analysis, Mathematical Modeling and Forecasting of the Development of the BRICS Countries. Preliminary Results / Ed. by A. A. Akaev, А. V. Korotayev, and S. Y. Malkov, pp. 10–31. Moscow: Krasand/ URSS. In Russian (Акаев А. А., Коротаев А. В., Малков С. Ю. Современная ситуация и контуры будущего. Комплексный системный анализ, математическое моделирование и прогнозирование стран БРИКС: Предварительные результаты / Ред. А. А. Акаев, А. В. Коротаев, С. Ю. Малков, с. 10–31. М.: Красанд).

Akaev A., Korotayev A., Issaev L., and Zinkina J. 2017. Technological Development and Protest Waves: Arab Spring as a Trigger of the Global Phase Transition? Technological Forecasting and Social Change 116: 316–321.

Akaev A. А., Sadovnichy V. А., and Korotayev А. V. 2010. On the Possibilities of Predicting the Current Global Crisis and Its Second Wave. Ekonomicheskaya politika 6: 39–46. In Russian (Акаев А. А., Садовничий В. А., Коротаев А. В. О возможностях предсказания нынешнего глобального кризиса и его второй волны. Экономическая политика 6: 39–46).

Akaev

A., Sadovnichy V., and Korotayev A. 2011. Explosive Rise

in Gold and Oil Prices as a Precursor of a Global Financial and Economic

Crisis. Doklady Matema-

tika 83(2):

1–4. In Russian (Акаев А. А., Садовничий В. А., Коротаев А. В. Взрывной

рост цен на золото и нефть как предвестник мирового финансово-экономического

кризиса. Доклады Математика 83(2): 1–4).

Akaev A., Sadovnichy V., and Korotayev A. 2012. On the Dynamics of the World Demographic Transition and Financial-Economic Crises Forecasts. The European Physical Journal 205: 355–373.

Allen R. C. 2011. Global Economic History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ayres R. 2006. Did the Fifth K-Wave Begin in 1990–92? Has It been Aborted by Globalization? Kondratieff Waves, Warfare and World Security / Ed. by T. Devezas, pp. 57–71. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Barro R. J. 1991. Economic Growth in a Cross Section of Countries. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 106(2): 407–443.

Berry B. J. L. 2000. A Pacemaker for the Long Wave. Technological Forecasting Social Change. 63(1): 1–23.

Berry B. J. L., and Elliott E. 2016. The Surprise that Transforms. An American Perspective on What the 2040s Might Bring. Kondratieff Waves: Cycles, Crises, and Forecasts / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, T. Devezas, and A. Korotayev, pp. 82–98. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Block W., and Rockwell Jr L. H. (Eds.) 2007. Man, Economy, and Liberty: Essays in Honor of Murray N. Rothbard. Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Bloom D. E., and Canning D. 2001. Demographic Change and Economic Growth: The Role of Cumulative Causality. Population Matters: Demography, Growth, and Poverty in the Developing World / Ed. by N. Birdsall, A. C. Kelley, and S. W. Sinding, pp. 165–197. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bloom D. E., and Canning D. 2008. Global Demographic Change: Dimensions and Economic Significance. Population and Development Review 34: 17–51.

Bloom D. E., Canning D., Fink G., and Finlay J. 2007a. Realizing the Demographic Dividend: Is Africa Any Different? Manuscript prepared for the African Economic Research Consortium.

Bloom D. E., Canning D., Fink G., and Finlay J. 2007b. Does Age Structure Forecast Economic Growth? International Journal of Forecasting 23(4): 569–585.

Bloom D. E., Canning D., and Malaney P. 2000. Demographic Change and Economic Growth in Asia. Population and Development Review 26(suppl): 257–290.

Bloom D. E., Canning D., and Sevilla J. 2003. The Demographic Dividend: A New Perspective on the Economic Consequences of Population Change. Population Matters Monograph MR-1274. RAND, Santa Monica.

Bloom D. E., and Sachs J. D. 1998. Geography, Demography and Economic Growth in Africa. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2: 207–295.

Bloom D. E., and Williamson J. G. 1998. Demographic Transitions and Economic Miracles in Emerging Asia. World Bank Economic Review 12(3): 419–455.

Clark G. 2008. A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Coccia M. 2018. A Theory of the General Causes of Long Waves: War, General Purpose Technologies, and Economic Change. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 128: 287–295. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.11.013.

Dator J. 2006. Alternative Futures for K-Waves. Kondratieff Waves, Warfare and World Security / Ed. by T. C. Devezas, pp. 311–317. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

de Groot B., and Frances P. H. 2008. Stability through Cycles. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 75: 301–311.

de Groot B., and Frances P. H. 2012. Common Socio-Economic Cycle Period. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 79: 59–68.

Derviş K. 2012. Convergence, Interdependence, and Divergence. Finance & Development 49(3): 10–14.

Devezas T. C. (Ed.) 2006. Kondratieff Waves, Warfare and World Security. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Devezas T. C., Leitão J., and Sarygulov A. (Eds.) 2017. Industry 4.0. Entrepreneurship and Structural Change in the New Digital Landscape. Heidelberg – New York – Dordrecht – London: Springer.

Devezas T. C., Linstone H. A., and Santos H. J. S. 2005. The Growth Dynamics of the Internet and the Long Wave Theory. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 72(8): 913–935.

Dickson D. 1983. Technology and Cycles of Boom and Bust. Science 219(4587): 933–936.

Diebolt C. 2012. Cliometrics of Economic Cycles in France. Kondratieff Waves. Dimensions and Prospects at the Dawn of the 21st Century / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, T. C. De-vezas, and A. V. Korotayev, pp. 120–137. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Diebolt C. 2014. Kuznets versus Kondratieff: An Essay in Historical Macroeconometrics. Cahiers d'Économie Politique 67: 81–117.

Diebolt C., and Doliger C. 2006. Economic Cycles under Test: A Spectral Analysis. Kondratieff Waves, Warfare and World Security. Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Research Workshop on the Influence of Chance Events and Socioeconomic Long Waves in the New Arena of Asymmetric Warfare, Covilhã, Portugal, 14–18 February 2005 / Ed. by T. C. Devezas, pp. 39–47. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Diebolt C., and Doliger C. 2008. New International Evidence on the Cyclical Behaviour of Output: Kuznets Swings Reconsidered. Quality & Quantity. International Journal of Methodology 42(6): 719–737.

Focacci A. 2017. Controversial Curves of the Economy: An Up-To-Date Investigation of Long Waves. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 116: 271–285.

Gallegati M. 2016. Wavelet Estimation of Kondratieff Waves: An Application to Long Cycles in Prices and World GDP. Kondratieff Waves: Cycles, Crises, and Forecasts / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, T. Devezas, and A. Korotayev, pp. 99–120. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Gallegati M., Gallegati M., Ramsey J. B., and Semmler W. 2017. Long Waves in Prices: New Evidence from Wavelet Analysis. Cliometrica 11(1): 127–151.

Garvy G. 1943. Kondratieff's Theory of Long Cycles. The Review of Economic Statistics 25(4): 203–220.

Goldstein J. 1988. Long Cycles: Prosperity and War in the Modern Age. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Goldstone J. A. 2008. Why Europe? The Rise of the West in Global History, 1500–1850. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Goldstone J. A. 2012. Divergence in Cultural Trajectories: The Power of the Traditional within the Early Modern. Comparative Early Modernities 1100–1800 / Ed. by D. Porter, pp. 165–192. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Goldstone J. A. 2015. Population Ageing and Global Economic

Growth. History & Mathematics: Political Demography & Global Ageing

/ Ed. by J. A. Goldstone,

L. E. Grinin, and A. V. Korotayev, pp.

147–155. Volgograd: ‘Uchitel’ Publishing House.

Grinin L. E., Devezas T., and Korotayev A. V. (Eds.) 2012. Kondratieff Waves. Dimensions and Perspectives at the Dawn of the 21st Century. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Grinin L. E., Devezas T., and Korotayev A. V. (Eds.) 2015. Kondratieff Waves. Juglar – Kuznets – Kondratieff. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Grinin L. E., Grinin A. L., and Korotayev A. 2017. Forthcoming Kondratieff Wave, Cybernetic Revolution, and Global Ageing. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 115: 52–68.

Grinin L. E., and Korotayev А. V. 2009. Global Crisis in Retrospect: A Brief History of Rises and Crises: From Lycurgus to Alan Greenspan. Moscow: LKI/URSS. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Коротаев А. В. Глобальный кризис в ретроспективе. Краткая история подъёмов и кризисов: от Ликурга до Алана Гринспена. М.: ЛКИ/УРСС).

Grinin L. E., and Korotayev А. V. 2012. Cycles, Crises, Traps of the Modern World System. The Study of Kondratieff, Juglar, and Secular Cycles, Global Crises, Malthusian and Post-Malthusian Traps. Moscow: LKI/URSS. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Коротаев А. В. Циклы, кризисы, ловушки современной Мир-Системы. Исследование кондратьевских, жюгляровских и вековых циклов, глобальных кризисов, мальтузианских и постмальтузианских ловушек. М.: ЛКИ/УРСС).

Grinin L. E., and Korotayev A. V. 2014a. Globalization Shuffles Cards of the World Pack. In Which Direction is the Global Economic-Political Balance Shifting? World Futures 70(8): 515–545.

Grinin L. E., and Korotayev А. V. (Eds.) 2014b. Kondratieff Waves: Long and Medium-Term Cycles. Volgograd: ‘Uchitel’. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Коротаев А. В. Кондратьевские волны: длинные и среднесрочные циклы. Волгоград: Учитель).

Grinin L. E., and Korotayev A. V. 2014с. Interaction between Kondratieff Waves and Juglar Cycles. Kondratieff Waves: Juglar – Kuznets – Kondratieff / Ed. by L. Grinin, T. Devezas, and A. Korotayev, pp. 25–95. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2015. Great Divergence and Great Convergence. A Global Perspective. Heidelberg – New York – Dordrecht – London: Springer.

Grinin L. E., Korotayev А. V., and Bondarenko V. М. (Eds.) 2015. Kondratieff Waves: Heritage and Modernity. Volgograd: ‘Uchitel’. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Коротаев А. В., Бондаренко В. М. Кондратьевские волны: наследие и современность. Волгоград: Учитель).

Grinin L. E., Korotayev А. V., and Malkov S. Y. 2010а. The Mathematical Model of the Medium-Term Economic Cycle. Forecast and Modeling of Crises and World Dynamics / Ed. by А. А. Akaev, А. V. Korotayev, G. G. Malinetskiy, pp. 287–299. Moscow: LKI/URSS. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Коротаев А. В. Математическая модель среднесрочного экономического цикла. Прогноз и моделирование кризисов и мировой динамики / Ред. А. А. Акаев, А. В. Коротаев, Г. Г. Малинецкий, с. 287–299. М.: ЛКИ/УРСС).

Grinin L. E., Korotayev

А. V., and Malkov S. Y. 2010b. The Mathematical Model of the Medium-Term Economic Cycle and the Modern

Global Crisis. History & Mathematics: Evolutionary Historical

Macrodynamics / Ed. by S. Yu. Malkov, L. E. Grinin, and А. V. Korotayev, pp. 233–284. Volgograd: ‘Uchitel’. In Russian (Гри-

нин Л. Е., Коротаев А., Малков С. Ю. Математическая модель среднего экономического

цикла и современный глобальный кризис. История и Математика: Эволюционная историческая макродинамика / Ред. Малков С. Ю., Гринин Л. Е., Коротаев

А. В., с. 233–284. Волгоград: Учитель).

Grinin L. E., Korotayev А. V., and Malkov S. Y. (Eds.) 2013. Kondratieff Waves: The Palette of Views. Volgograd: ‘Uchitel’. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Коротаев А. В., Малков С. Ю. Кондратьевские волны: Палитра взглядов. Волгоград: Учитель).

Grinin L., Korotayev A., and Tausch A. 2016. Economic Cycles, Crises, and the Global Periphery. Heidelberg – New York – Dordrecht – London: Springer.

Grinin L. E., Korotayev А. V., and Tsirel S. V. 2011. The Cycles of the Development of the Modern World System. Moscow: LKI/URSS. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Коротаев А. В., Цирель С. В. Циклы развития современной Мир-Системы. М.: ЛКИ/УРСС).

Grinin L., Tsirel S., and Korotayev A. 2014. Will the Explosive Growth of China Continue? Technological Forecasting & Social Change 95: 294–308.

Hawksworth J., and Cookson G. 2008. The World in 2050. Beyond the BRICs: A Broader Look at Emerging Market Growth Prospects. London: Pricewaterhouse Coopers.

Jourdon Ph. 2008. La monnaie unique europeenne et son lien au developpement economique et social coordonne: une analyse cliometrique. Thèse. Montpellier: Universite Montpellier I.

Juglar C. 1862. Des crises commerciales et de leur retour périodique en France, en Angleterre et aux États-Unis. Paris: Guillaumin.

Kondratieff N. D. 1922. World Economy and its Conjuncture during and After the War. Vologda: Oblastnoye otdeleniye Gosudarstvennogo izdatel'stva. In Russian (Кондратьев Н. Д. Мировое хозяйство и его конъюнктура во время и после войны. Вологда: Областное отделение Государственного издательства).

Kondratieff N. D. 1925. Long Cycles of Conjuncture. Voprosy konyunktury 1(1): 28–79. In Russian (Кондратьев Н. Д. Большие циклы конъюнктуры. Вопросы конъюнктуры 1(1): 28–79.

Kondratieff N. D. 1926. Die langen Wellen der Konjunktur. Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik 56(3): 573–609.

Kondratieff N. D. 1928a. Long Cycles of Conjuncture. Мoscow: Institut ekonomiki RAN. In Russian (Кондратьев Н. Д. Большие циклы конъюнктуры. М.: Институт экономики РАН).

Kondratieff N. D. 1928b. Die Preisdynamik der industriellen und landwirtschaftlichen Waren. Zum Problem der relativen Dynamik der Konjunktur. Archiv fuer Sozialwissenschaften und Sozialpolitik 60(1): 1–85.

Kondratieff N. D. 1935. The Long Waves in Economic Life. Review of Economic Statistics 17(6): 105–115.

Kondratieff N. D. 1979. The Long Waves in Economic Life. Review of Fernand Braudel Center 2(4): 519–562.

Kondratieff N. D. 1984. The Long Wave Cycle. New York: Richardson & Snyder.

Kondratieff N. D. 1998. The Works of Nikolai D. Kondratiev / Ed. by W. Samuels, N. Makasheva, and V. Barnett, 4 vols. London: Pickering and Chatto.

Kondratieff N. D. 2002. Long Cycles of Economic Conjuncture and the Theory of Foresight. Moscow: Ekonomika. In Russian (Кондратьев Н. Д. Большие циклы конъюнктуры и теория предвидения. М.: Экономика).

Kondratieff N. D. 2004 [1922]. The World Economy and Its Conjunctures During and After the War. Moscow: International Kondratieff Foundation [English translation of the 1922 original].

Korotayev А. V. 2013. The Structure of Modern Global Convergence: A Quantitative Analysis. Econometric Methods in Global Processes Research / Ed. by A. A. Petrov, pp. 101–111. Мoscow: Ankil. In Russian (Коротаев А. В. Структура современной глобальной конвергенции: количественный анализ. Эконометрические методы в исследовании глобальных процессов / Ред. А. А. Петров, с. 101–111. М.: Анкил).

Korotayev А. V. 2014. Great Divergence, Great Convergence and Global Demographic Transition. The World Economy of the Nearest Future: Wh ere to Expect an Innovative Breakthrough? / Ed. by V. M. Bondarenko, pp. 39–51. Мoscow: International Kondratieff Foundation. In Russian (Коротаев А. В. Большая дивергенция, большая конвергенция и глобальный демографический переход. Мировая экономика ближайшего будущего: откуда ждать инновационного рывка? / Ред. В. М. Бондаренко, с. 39–51. М.: Международный Фонд Кондратьева).

Korotayev А. V. 2015а. Global Demographic Transition and Phases of Divergence – Convergence of the Center and Periphery of the World-System. Vestnik Instituta ekonomiki Rossijskoj akademii nauk 1: 149–162. In Russian (Коротаев А. В. Глобальный демографический переход и фазы дивергенции – конвергенции центра и периферии Мир-Системы. Вестник Института экономики Российской академии наук 1: 149–162).

Korotayev А. V. 2015b. Mathematical Modeling of the Processes of the Great Divergence and the Great Convergence. Sociophysics and Socioengineering / Ed. by Yu. L. Slovokhotov, pp. 16–17. Moscow: MGU. In Russian (Коротаев А. В. Математическое моделирование процессов Великой дивергенции и Великой конвергенции. Социофизика и социоинженерия / Ред. Ю. Л. Словохотов, с. 16–17. М.: МГУ).

Korotayev A. V. 2020. The 21st Сentury Singularity in the Big History Perspective. A Re-Analysis. The 21st Century Singularity and Global Futures. A Big History Perspective / Ed. by A. V. Korotayev, and D. LePoire, pp. 19–75. Cham: Springer.

Korotayev А. V., Andreev А. I., Zinkina Yu. V., and Folomeeva D. A. 2014. On the Structure of Global Convergence. Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta. Seriya XXVII. Globalistika i geopolitika 3(4): 74–83. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Андреев А. И., Зинкина Ю. В., Фоломеева Д. А. О структуре глобальной конвергенции. Вестник Московского университета. Серия 27. Глобалистика и геополитика 3(4): 74–83).

Korotayev А. V., and Bozhevolnov Yu. V. 2010. Some General Trends in the Economic Development of the World-System. Forecast and Modeling of Crises and World Dynamics / Ed. by А. А. Akaev, А. V. Korotayev, and G. G. Malinetskiy, pp. 161–172. Мoscow: LKI/URSS. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Божевольнов Ю. В. Некоторые общие тенденции экономического развития Мир-Системы. Прогноз и моделирование кризисов и мировой динамики / Ред. А. А. Акаев, А. В. Коротаев, Г. Г. Малинецкий, с. 161–172. М.: ЛКИ/УРСС).

Korotayev A., and de Munck V. 2013. Advances in Development Reverse Inequality Trends. Journal of Globalization Studies 4(1): 105–124.

Korotayev A., and de Munck V. 2014. Advances in Development Reverse Global Inequality Trends. Globalistics and Globalization Studies: Aspects & Dimensions of Global Views / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, I. V. Ilyin, and A. V. Korotayev, pp. 164–183. Volgograd: ‘Uchitel’ Publishing House.

Korotayev A., Goldstone J., and Zinkina J. 2015. Phases of Global Demographic Transition Correlate with Phases of the Great Divergence and Great Convergence. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 95: 163–169.

Korotayev A., and Grinin L. 2012a. Kondratieff Waves in the World System Perspective. Kondratieff Waves:

Dimensions and Prospects / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, T. C. De-

vezas, and A. V. Korotayev, pp. 23–64. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Korotayev А. V., and Grinin L. E.

2012b.

Kondratieff Waves in the World-System Perspective. Kondratieff

Waves: Aspects and Prospects / Ed. by А. А. Akaev,

R. S. Grinberg, L. E. Grinin, А. V. Korotayev, and S. Y. Malkov, pp. 58–109. Volgograd: ‘Uchitel’. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Гринин Л. Е. Кондратьевские волны в

мир-системной перспективе. Кондратьевские волны: Аспекты и перспективы /

Ред. Акаев А. А., Гринберг Р. С., Гринин Л. Е., Коротаев А. В., Малков С. Ю.,

с. 58–109. Волгоград: Учитель).

Korotayev А. V., and Khaltourina D. А. 2009. Current Trends of the World Development. Мoscow: LIBROKOM/URSS. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Халтурина Д. А. Современные тенденции мирового развития. М.: ЛКИ/УРСС).

Korotayev А. V., Khaltourina D. А., Malkov A. S., Bozhevolnov Yu. V., Kobzeva S. V., and Zinkina Yu. V. 2010. Laws of History. Mathematical Modeling and Fore-casting of World and Regional Development. 3rd ed. М.: LKI/URSS. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Халтурина Д. А., Малков А. С., Божевольнов Ю. В., Кобзева С. В., Зинькина Ю. В. Законы Истории. Математическое моделирование и прогнозирование мирового и регионального развития. М.: ЛКИ/УРСС).

Korotayev А. V., Malkov А.S., Bozhevol'nov Yu. V., and Khaltourina D. А. 2010. To the System Analysis of Global Dynamics: The Interaction of the Center and the Periphery of the World System. Globalistics as a Field of Scientific Research and the Field of Teaching / Ed. by I. I. Abylgaziev, I. V. Ilyin, and T. L. Shestova, pp. 228–242. Мoscow: МАKS-Press. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Малков А. С., Божевольнов Ю. В., Халтурина Д. А. K системному анализу глобальной динамики: взаимодействие центра и периферии Мир-Системы. Глобалистика как область научных исследований и сфера преподавания / Ред. И. И. Абылгазиев, И. В. Ильин, Т. Л. Шестова, с. 228–242. М.: МАКС-Пресс).

Korotayev A., and Tsirel S. 2010a. A Spectral Analysis of World GDP Dynamics: Kondratieff Waves, Kuznets Swings, Juglar and Kitchin Cycles in Global Economic Development, and the 2008–2009 Economic Crisis. Structure and Dynamics 4(1): 3–57. URL: http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/9jv108xp.

Korotayev А., and Tsirel S. 2010b. Kondratieff Waves in the World Economic Dynamics. System Monitoring of Global and Regional Development / Ed. by D. A. Khaltourina, and А. V. Korotayev, pp. 189–229. Мoscow: LIBROKOM/URSS. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Цирель С. Кондратьевские волны в мировой экономической динамике. Системный мониторинг глобального и регионального развития / Ред. Д. А. Халтурина, А. В. Коротаев, с. 189–229. М.: ЛКИ/УРСС).

Korotayev А., and Tsirel

S. 2010c. Kondratieff Waves in the World-System Economic Dynamics. Forecast

and Modeling of Crises and World Dynamics / Ed. by

А. А. Akaev, А. V. Korotayev, G. G. Malinetskiy, pp. 5–69. Мoscow: LKI/URSS. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Цирель С. Кондратьевские волны в мир-системной экономической динамике. Прогноз и моделирование

кризисов и мировой динамики / Ред. А. А.

Акаев, А. В. Коротаев, Г. Г. Малинецкий, с. 5–69. М.:

ЛКИ/УРСС).

Korotayev А. V., and Zinkina J. V. 2012. Is Tropical Africa in the Malthusian Trap? To the Modeling and Forecasting of the Socio-Demographic Development of Africa to the South of the Sahara. Informatsionnyj byulleten Assotsiatsii ‘Istoriya i kompyuter’ 38: 77–79. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Зинькина Ю. В. Тропическая Африка в мальтузианской ловушке? К моделированию и прогнозированию социально-демографического развития Африканской южнее Сахары. Информационный бюллетень ассоциации ‘История и компьютер’ 38: 77–79).

Korotayev A., and Zinkina J. 2014a. How to Optimize Fertility and Prevent Humanitarian Catastrophes in Tropical Africa. African Studies in Russia 6: 94–107.

Korotayev A., and Zinkina J. 2014b. On the Structure of the Present-Day Convergence. Campus-Wide Information Systems 31(2–3): 139–152.

Korotayev А. V., and Zinkina J. V. 2014c. On The Decline in the Birth Rate as a Condition of Socio-Economic Stability in the Least Developed Countries. World Dynamics: Regularities, Trends, Prospects / Ed. by А. А. Akaev, А. V. Korotayev, and S. Y. Malkov, pp. 243–263. Мoscow: Krasand/URSS. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Зинькина Ю. В. О снижении рождаемости как условии социально-экономической стабильности в наименее развитых странах. Мировая динамика: Закономерности, тенденции, перспективы / Ред. А. А. Акаев, А. В. Коротаев, С. Ю. Малков, с. 243–263. М.: Красанд/УРСС).

Korotayev A., and Zinkina J. 2015. East Africa in the Malthusian Trap? Journal of Developing Societies 31(3): 1–36.

Korotayev A., Zinkina J., and Bozhevolnov J. 2011. Kondratieff Waves in Global Invention Activity (1900–2008). Technological Forecasting & Social Change 78: 1280–1284.

Korotayev A., Zinkina J., Bozhevolnov Yu., and Malkov A. 2011a. Global Unconditional Convergence among Larger Economies after 1998? Journal of Globalization Studies 2(2): 25–62.

Korotayev A., Zinkina J., Bozhevolnov J., and Malkov A. 2011b. Unconditional Convergence among Larger Economies. Great Powers, World Order and International Society: History and Future / Ed. by Debin Liu, pp. 70–107. Changchun: The Institute of International Studies – Jilin University.

Korotayev A., Zinkina J., Bozhevolnov J., and Malkov A. 2012. Unconditional Convergence among Larger Economies after 1998? Globalistics and Globalization Studies / Ed. by L. Grinin, I. Ilyin, and A. Korotayev, pp. 246–280. Moscow – Volgograd: Moscow University – Uchitel.

Lee R., and Mason A. 2006. What is the Demographic Dividend? Finance and Development 43(3): 16–17.

Lee R., and Mason A. 2011. Population Aging and the Generational Economy: A Global Perspective. London: Edward Elgar.

Linstone H. 2006. The Information and Molecular Ages: Will K-Waves Persist? Kondratieff Waves, Warfare and World Security / Ed. by T. Devezas, pp. 260–269. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Linstone H. A., and Devezas T. 2012. Technological Innovation and the Long Wave Theory Revisited. Technological Forecasting Social Change 79(2): 414–416.

Lynch Z. 2004. Neurotechnology and Society 2010–2060. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1031: 229–233.

Maddison A. 2010. World Population, GDP and Per Capita GDP, A.D.1–2008. URL: www.ggdc.net/maddison.

Malkov А. S., Bozhevolnov J. V., Khaltourina D. А., and Korotayev А. V. 2010a. To the System Analysis of Global Dynamics: The Interaction of the Center and the Periphery of the World System. Forecast and Modeling of Crises and World Dynamics / Ed. by А. А. Akaev, А. V. Korotayev, and G. G. Malinetskiy, pp. 234–248. Мoscow: LKI/URSS. In Russian (Малков А. С., Божевольнов Ю. В., Халтурина Д. А., Коротаев А. В. К системному анализу мировой динамики: взаимодействие Центра и Периферии Мир-Системы. Прогноз и моделирование кризисов и мировой динамики / Ред. А. А. Акаев, А. В. Коротаев, Г. Г. Малинецкий, с. 234– 248. М.: ЛКИ/УРСС).

Malkov А. S., Korotayev А. V., and Bozhevolnov Yu. V. 2010b. Mathematical Modeling of the Interaction of the Center and Periphery of the World-System. Forecast and Modeling of Crises and World Dynamics / Ed. by А. А. Akaev, А. V. Korotayev, and G. G. Malinetskiy, pp. 277–286. Мoscow: LKI/URSS. In Russian (Малков А. С., Коротаев А. В., Божевольнов Ю. В. Математическое моделирование взаимодействия центра и периферии Мир-Системы. Прогнозирование и моделирование кризисов и мировой динамики / Ред. А. А. Акаев, А. В. Коротаев, Г. Г. Малинецкий, с. 277–286. М.: ЛКИ/УРСС).

Malkov S. Yu., and Korotayev А. V. 2014. Evolution of the World System: The Decline of the West and the Rise of the East. Prospects and Strategic Priorities for the Rise of BRICS / Ed. by V. A. Sadovnichiy, Y. V. Yakovets, A. A. Akaev, pp. 149–160. Мoscow: Natsional'nyj komitet po issledovaniyu BRIKS. In Russian (Малков А. С., Коротаев А. В. Эволюция Мир-Системы: закат Запада и восхождение Востока. Перспективы и стратегические приоритеты восхождения Брикс / Ред. В. А. Садовничий, Ю. В. Яковец А. А. Акаев, с. 149–160. М.: Национальный комитет по исследованию БРИКС).

Mandel E. 1980. Long Waves of Capitalist Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mankiw N. G. 1989. Real Business Cycles: A New Keynesian Perspective. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 3(3): 79–90.

Mankiw N. G. 2008. Principles of Economics. 5th ed. Mason, OH: South-Western.

Mankiw N. G. 2015. Principles of Economics. 7th ed. Mason, OH: South-Western.

Mankiw N. G., Romer D., and Weil D. N. 1992. A Contribution to the Empirics of Economic Growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 107(2): 407–437.

Marchetti C. 1980. Society as a Learning System. Discovery, Invention and Innovation Cycles Revisited. Technological Forecasting Social Change 18(4): 267–282.

Marchetti C. 1983. Recession 1983: Ten More Years to Go? Technological Forecasting Social Change 24: 331–334.

Marchetti C. 1986. Fifty Years Pulsation in Human Affairs. Futures 17(3): 376–388.

Marchetti C., and Nakicenovic N. 1979. The Dynamics of Energy Systems and the Logistic Substitution Model. Laxenburg: International Institute for Applied System Analysis.

Mason A. (Ed.) 2001. Population Change and Economic Development in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia: Challenges Met, Opportunities Seized. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Mason A. 2007. Demographic Transition and Demographic Dividends in Developed and Developing Countries. Proceedings of the United Nations Expert Group Meeting on Social and Economic Implications of Changing Population Age Structures Mexico City. 31 August – 2 September 2005, pp. 81–101. New York, NY: United Nations.

Mensch G. 1979. Stalemate in Technology – Innovations Overcome the Depression. New York, NY: Ballinger.

Metz R. 1998. Langfristige Wachstumsschwankungen – Trends, Zyklen, Strukturbrüche oder Zufall? Kondratieffs Zyklen der Wirtschaft. An der Schwelle neuer Vollbeschäftigung? / Ed. by H. L. Thomas, and A. Nefiodow, pp. 283–307. Herford.

Metz R. 2006. Empirical Evidence and Causation of Kondratieff Cycles. Kondratieff Waves, Warfare and World Security / Ed. by T. C. Devezas, pp. 91–99. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Modelski G. 2001. What Causes K-Waves? Technological Forecasting Social Change 68: 75–80.

Modelski G., and Thompson W. R. 1996. Leading Sectors and World Politics: The Coevolution of Global Politics and Economics. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Modis T. 2002. Forecasting the Growth of Complexity and Change. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 69(4): 377–404.

Modis T. 2017. A Hard-Science Approach to Kondratieff's Economic Cycle. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 122: 63–70.

Modis T. 2019. Forecasting

the Growth of Complexity and Change – An Update. The 21st century

Singularity and Global Futures. A Big History Perspective / Ed. by

A. V. Korotayev, and D. LePoire, pp. 101–104. Cham: Springer.

Morineau M. 1984. Jugular, Kitchin, Kondratieff, et compagnie. Review 7(4): 577–598.

Nefiodow L.

2016. The Sixth Kondratieff – The New Long Wave of the Global Economy. Kondratieff Waves: Cycles, Crises, and

Forecasts / Ed. by L. E. Grinin,

T. Devezas, and A. Korotayev, pp. 203–209. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Norkus Z. 2016. On Global Social Mobility, or How Kondratieff Waves Change the Structure of the Capitalist World System. Kondratieff Waves: Cycles, Crises, and Forecasts / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, T. Devezas, and A. Korotayev, pp. 121–152. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Ogawa N., Kondo M., and Matsukura R. 2005. Japan's Transition from the Demographic Bonus to the Demographic Onus. Asian Population Studies 1(2): 207–226.

Pantin V., and Lapkin V. 2006. The Philosophy of Historical Forecasting: Rhythms and Prospects for the World Development in the First Half of the Twenty-First Century. Dubna: Feniks+. In Russian (Пантин В., Лапкин В. Философия исторического прогнозирования: ритмы и перспективы мирового развития в первой половине XXI века. Дубна: Феникс+).

Park D., and Shin K. 2015. Impact of Population Ageing on Asia's Future Growth. History & Mathematics: Political Demography & Global Ageing / Ed. by J. A. Goldstone, L. E. Grinin, and A. V. Korotayev, pp. 107–132. Volgograd: ‘Uchitel’ Publishing House.

Phillips F. Y. 2016. The Circle of Innovation. Journal of Innovation Management 4(3): 12–31.

Phillips F. Y. 2018. Multiplicity and Divergence Challenge the Social Sciences. Kondratieff Waves: The Spectrum of Opinions / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, and A. V. Korotayev, pp. 145–152. Volgograd: ‘Uchitel’ Publishing House.

Phillips F. Y., and Linstone H. 2016. Key Ideas from a 25-Year Collaboration at Technological Forecasting & Social Change. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 105: 158–166.

Plys K. 2012. World Systemic and Kondratieff Cycles. Yale Journal of Sociology 9: 130–160.

Plys K. 2014. Financialization, Crisis, and the Development of Capitalism in the USA. World Review of Political Economy 5(1): 24–44.

Pomeranz K. 2000. The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Quah D. T. 1996. Convergence Empirics Across Economies with (Some) Capital Mobility. Journal of Economic Growth 1(1): 95–124.

Rostow W. W. 1975. Kondratieff, Schumpeter and Kuznets: Trend Periods Revisited. Journal of Economic History 25(4): 719–753.

Rothbard M. 1984. The Kondratieff Cycle: Real or Fabricated? Investment Insights 4: 1–9.

Sadovnichy V. А., Akaev А. А., Korotayev А. V., and Malkov S. Yu. 2012. Modeling and Forecasting of World Dynamics. Мoscow: ISPI RAN. In Russian (Садовничий В. А., Акаев А. А., Коротаев А. В., Малков С. Ю. Моделирование и прогнозирование мировой динамики. М.: ИСПИ РАН).

Sadovnichy V. А., Akaev А. А., Korotayev А. V., and Malkov S. Y. 2014. Complex Modeling and Forecasting of the Development of the BRICS Countries in the Context of the World Dynamics. Мoscow: Nauka. In Russian (Садовничий В. А., Акаев А. А., Коротаев А. В., Малков С. Ю. Комплексное моделирование и прогнозирование развития стран БРИКС в контексте мировой динамики. М.: Наука).

Sala-i-Martin X. X. 1996. The Classical Approach to Convergence Analysis. The Economic Journal 106(437): 1019–1036.

Sala-i-Martin X. X. 2006. The World Distribution of Income: Falling Poverty and… Convergence, Period. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 121(2): 351–397.

Schumpeter J. A. 1939. Business Cycles. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Schwartz A. J. 1987. Money in Historical Perspective. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Sokolov V., Devezas T., and Rumyantseva S. 2017. On the Asymmetry of Economic Cycles. Industry 4.0. Entrepreneurship and Structural Change in the New Digital Landscape / Ed. by T. Devezas, J. Leitão, and A. Sarygulov, pp. 65–92. Heidelberg – New York – Dordrecht – London: Springer.

Spence M. 2011. The Next Convergence: The Future of Economic Growth in a Multispeed World. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Tausch A. 2006. Global Terrorism and World Political Cycles. History & Mathematics: Analyzing and Modeling Global Development / Ed. by L. Grinin, V. C. de Munck, and A. Korotayev, pp. 99–126. Moscow: KomKniga/URSS.

Tausсh A. 2016. Kaname Akamatsu. Biography and Long Cycles Theory. Kondratieff Waves: Cycles, Crises, and Forecasts / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, T. Devezas, and A. Korotayev, pp. 65–81. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Thompson W. 2007. The Kondratieff Wave as Global Social Process.

World System History, Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems, UNESCO / Ed.

by G. Modelski,

and R. Denemark. Oxford: EOLSS Publishers.

Thompson W. 2016. Revising a Long-Term Perspective on Kondratieff Phenomena. Kondratieff Waves: Cycles, Crises, and Forecasts / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, T. Devezas, and A. Korotayev, pp. 203–209. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Tugan-Baranovsky M. I. 2008 [1913]. Periodic Industrial Crises. Мoscow: Direktmedia Publishing. In Russian (Туган-Барановский М. И. Периодические промышленные кризисы. М.: Директ-Медиа).

UN Population Division. 2019. UN Population Division Database. URL: http://www.un.org/esa/population.

van Duijn J. 1983. The Long Wave in Economic Life. Boston: Allen and Unwin.

van Ewijk C. 1982. A Spectral Analysis of the Kondratieff Cycle. Kyklos 35(3): 468–499.

Vassiliev A. M., Zinkina J. V., Korotayev A. V., Issaev L. M., Sledzevskiy I. V., Sukhov N. V., Malkov S. Yu., and Hamatshin A. D. 2014. Demographic Background of the Arab Crisis and Socio-Demographic Risks of Tropical Africa. The Arab Crisis and Its International Consequences / Ed. by A. M. Vassiliev, A. D. Savateyev, and L. M. Issaev, pp. 29–55. Moscow: Lenand/URSS. In Russian (Васильев А. М., Зинькина Ю. В., Коротаев А. В., Исаев Л. М., Следзевский И. В., Сухов Н. В., Малков С. Ю., Хаматшин A. Д. Демографические предпосылки Арабского кризиса и социально-демографические риски Тропической Африки. Арабский кризис и его международные последствия / Ред. А. М. Васильев, А. Д. Саватеев, Л. М. Исаев, с. 29–55. М.: Ленанд/УРСС).

Volland C. S. 1987. A Comprehensive Theory of Long Wave Cycles. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 32(2): 123–145.

Wallerstein I. 1984. Economic Cycles and Socialist Policies. Futures 6(16): 579–585.

Wilenius M., and Casti J. 2014. Seizing the X-Events. The Sixth K-Wave and the Shocks that May Upend It. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 94: 335–349.

World Bank. 2019. World Development Indicators Online. Washington, DC: World Bank. URL: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/.

Zarnowitz V. 1985. Recent Work on Business Cycles in Historical Perspective: Review of Theories and Evidence. Journal of Economic Literature 23(2): 523–580.

Zinkina Yu., and Korotayev А. 2013а. How to Optimize the Birth Rate and Prevent Humanitarian Disasters in the Countries of Tropical Africa. Aziya i Afrika segodnya 4: 28–35. In Russian (Зинькина Ю., Коротаев А. Как оптимизировать рождаемость и предотвратить гуманитарные катастрофы в странах Тропической Африки. Азия и Африка сегодня 4: 28–35).

Zinkina Yu., and Korotayev А. 2013b. Modeling the Impact of Secondary Education on Scenarios of Tanzania's Socio-Demographic Dynamics. Informatsionnyj byulleten' Assotsiatsii ‘Istoriya i komp'yuter’ 40: 70–74. In Russian (Зинькина Ю., Корота-ев А. Моделирование влияния распространения среднего образования на сценарий социально-демографической динамики Танзании. Информационный бюллетень Ассоциации ‘История и компьютер’ 40: 70–74).

Zinkina Yu., and Korotayev A. 2014a. Explosive Population Growth in Tropical Africa: Crucial Omission in Development Forecasts (Emerging Risks and Way out). World Futures 70(4): 271–305.

Zinkina Yu., and Korotayev A. 2014b. Projecting Mozambique's Demographic Futures. Journal of Futures Studies 19(2): 21–40.

Zinkina Yu., Malkov A., and Korotayev A. 2014. A Mathematical Model of Technological, Economic, Demographic and Social Interaction Between the Center and Periphery of the World System. Socio-Economic and Technological Innovations: Mechanisms and Institutions / Ed. by K. Mandal, N. Asheulova, and S. G. Kirdina, pp. 135–147. New Delhi: Narosa Publishing House.

[1] For Kondratieff waves/long cycles see also, e.g., Schumpeter 1939; Rostow 1975; Mensch 1979; Marchetti and Nakicenovic 1979; Mandel 1980; Marchetti 1980, 1983, 1986; Volland 1987; Berry 2000; Modelski 2001; Devezas, Linstone, and Santos 2005; Devezas 2006; Dator 2006; de Groot and Frances 2008, 2012; Grinin, Devezas, and Korotayev 2012, 2015; Korotayev, Zinkina, and Bozhevolnov 2011; Sadovnichiy et al. 2012; Linstone and Devezas 2012; Grinin, Korotayev, and Malkov 2013; Grinin, Korotayev, and Bondarenko 2015; Wilenius and Casti 2014; Phillips and Linstone 2016.

[2] Even without any additional smoothing.

[3] For more information about this global trend inflection, see, e.g., Korotayev, Malkov et al. 2010; Korotayev and Bozhevolnov 2010; Sadovnichiy et al. 2014; Malkov and Korotayev 2014; Akaev, Ko-rotayev, and Malkov 2014; Korotayev 2020.

[4] For more information about these cycles, see, e.g., Juglar 1862; Tugan-Baranovsky 2008 [1913]; Schumpeter 1939; Grinin, Korotayev, and Malkov 2010a, 2010b; Grinin and Korotayev 2009, 2012; Grinin, Korotayev, and Malkov 2010b; Grinin and Korotayev 2015b.

[5] See, e.g., Barro 1991; Mankiw et al. 1992; Quah 1996; Sala-i-Martin 1996; Acemoglu 2009; Korotayev, Malkov et al. 2010; Malkov, Bozhevolnov et al. 2010; Sadovnichiy et al. 2014.

[6] For a demographic bonus, see, e.g., Bloom and Williamson 1998; Bloom and Sachs 1998; Bloom, Canning, and Malaney 2000; Bloom and Canning 2001, 2008; Bloom, Canning, and Sevilla 2003; Bloom et al. 2007a, 2007b; Mason 2001, 2007; Hawksworth and Cookson 2008: 7–10; Lee and Mason 2006, 2011.

[7] This, of course, is applicable to most developing countries (and to the ‘developing countries’ aggregate as a whole). At the same time, it is obvious that some developing countries should reach the GDP growth rates per capita at the peak of the sixth K-wave significantly exceeding those reached by them at the peak of the fifth wave. This is particularly true for the least developed countries that are still far enough from the end of the demographic transition, and which will receive their main demographic bonus just at the upward phase of the sixth K-wave (if, of course, they will soon be able to accelerate the rate of decline birth rate [see, e.g. Vassiliev et al. 2014; Zinkina and Korotayev 2013а, 2013b, 2014a, 2014b; Korotayev and Zinkina 2012, 2014a, 2014c, 2015]).